When the coronavirus hit in 2020, almost USD 14 trillion was committed globally in initial government responses to the pandemic.

This was often done by circumventing existing budget processes in the name of emergency needs. For example, the usual timing of the budget was changed and procedural dates and processes were rushed or avoided; legislatures were bypassed in executive decisions about spending; the public was not consulted; and information about expenditures, programs or the pandemic itself was not released.

Just as the virus has put an enormous strain on our health and economic systems, it has also put our budget systems to the test.

To identify whether governments passed the ‘budget accountability’ test, local researchers from 120 countries have partnered with the Washington-based International Budget Partnership (IBP) to assess almost 400 national COVID-19 response packages from these countries, which occurred during the period from March to September 2020. This includes the Australian economic and health response packages, which were assessed by the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute (TTPI) at the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy. The check on COVID-19 budgeting forms part of the IBP’s biennial Open Budget Survey.

Indeed, what we found globally is widespread weaknesses in transparency and oversight of national COVID-19 budgeting. These results are not entirely unexpected, but they are still of concern.

The challenges of accountability in COVID-19 budgeting

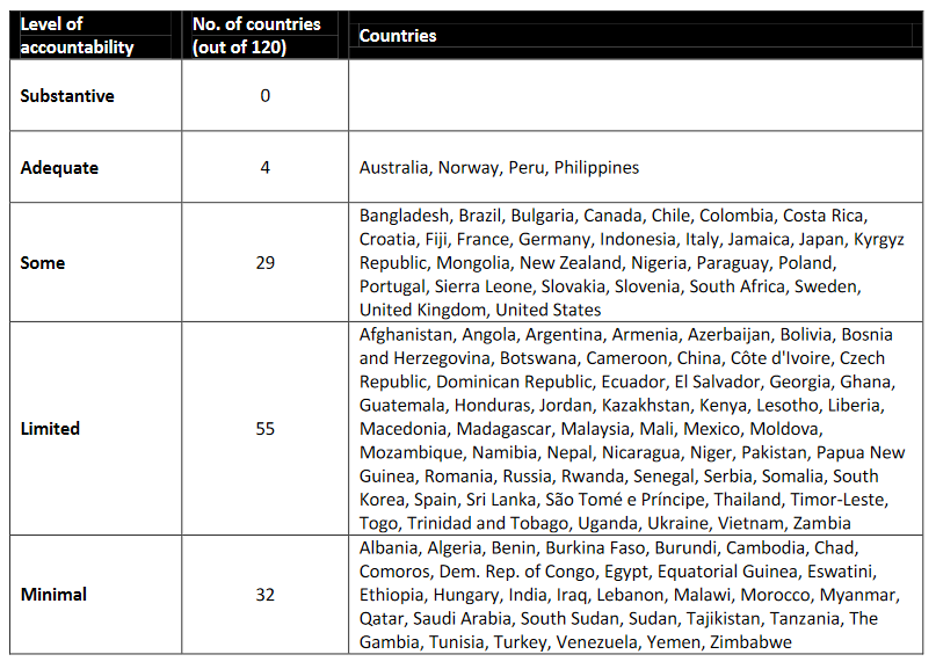

The IBP survey shows that more than two thirds of countries surveyed (87 out of 120) failed to manage their immediate fiscal policy response to the pandemic in a transparent and accountable manner. Only four countries – including Australia – were found to have adequate levels of accountability.

Table 1: Levels of accountability in early COVD fiscal policy responses

Source: Managing COVID funds: the accountability gap, 2021. Note: Countries were assessed using 26 indicators on transparency, oversight and public participation, in stages from formulation through implementation and audit. Scores were aggregated and countries were then rated by performance categories. Substantive accountability indicates scores of 0.81 to 1.00, adequate accountability indicates 0.61 to 0.80, some accountability indicates 0.41 to 0.60, limited accountability indicates 0.21 to 0.40 and minimal accountability indicates 0 to 0.20.

The study also found that:

- Almost two thirds of national governments surveyed failed to provide transparency in pandemic-related procurement;

- Almost half of governments bypassed their legislatures to introduce COVID-19 fiscal packages;

- Only one quarter of national auditors published expedited audit reports;

- Only three countries published a gender impact assessment; and

- There was very limited citizen participation in the formulation and implementation of COVID-19 fiscal packages.

The study did document examples of good practices, where governments seeking to respond quickly nonetheless sought to uphold transparency and participation and to keep budget oversight functioning at the height of the pandemic.

The best examples reveal governments using digital technologies, for example setting up a dedicated one-stop website for the pandemic and its related response measures, and applying videoconferencing to enable meetings of the legislature or public consultations.

Australia budgeted “adequately” for the pandemic

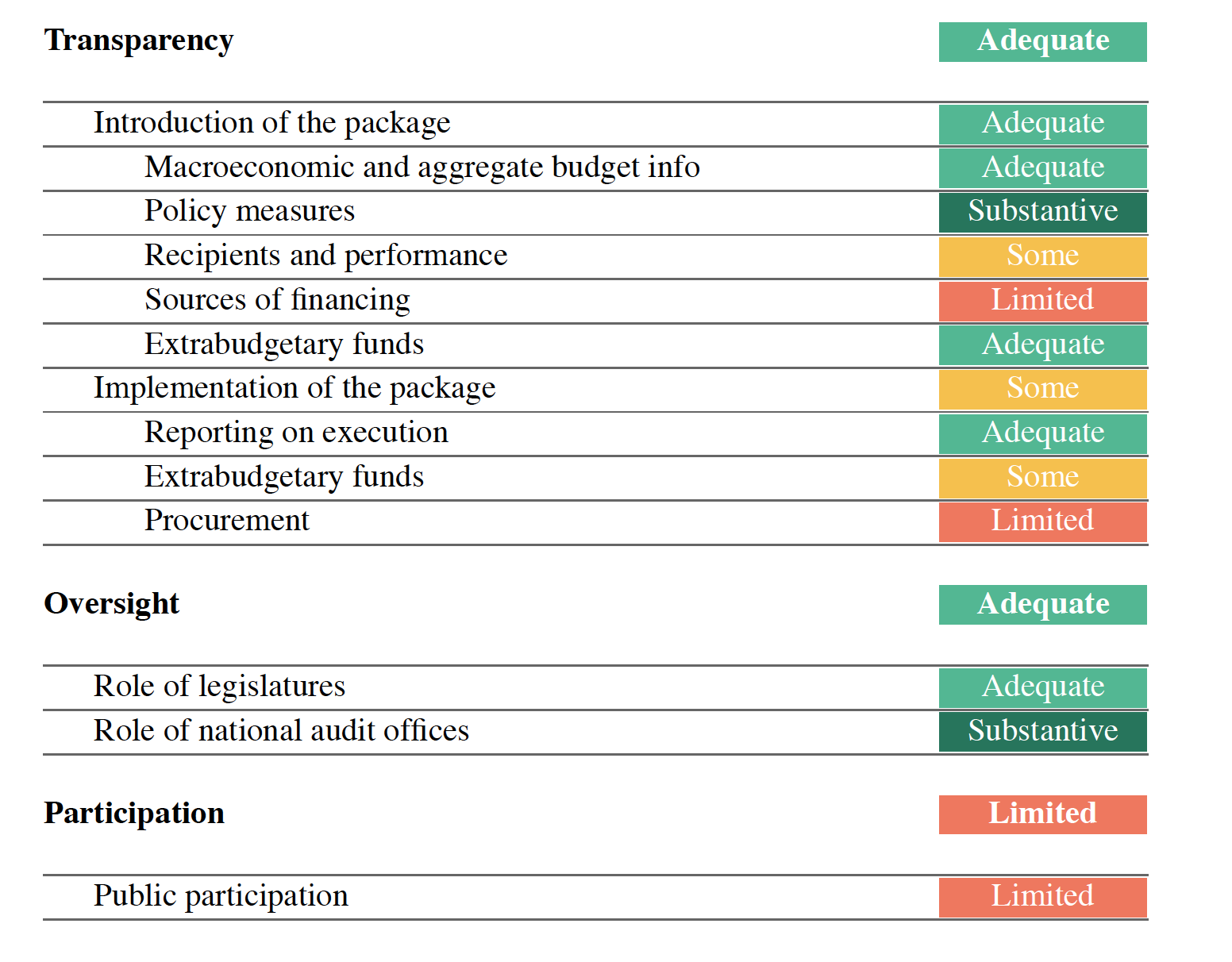

Australia’s ranking as one of the best performing countries on fiscal accountability for our COVID-19 response is consistent with our past budget transparency performance. The findings for Australia are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Transparency and accountability of Australia’s COVID-19 fiscal response

Some good budget practices and innovation by the Australian Government during the pandemic include delivering the July 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update and establishing an Opposition-chaired Senate select committee including seven members of the Senate to monitor and report on the Government’s response to the pandemic.

The July 2020 Update performed the function of a pre-budget statement for the October 2020-21 budget (after the usual May budget was postponed), which helped to set budget expectations and encourage debate on the government’s budget strategies that were elaborated in October. A publicly available pre-budget statement had been a missing piece in Australia’s budget process, as we have documented in previous IBP Surveys.

The select committee enabled some legislative oversight of the Government’s COVID-19 response, after fiscal legislation was fast-tracked to allow a quick response. Despite Parliament only meeting intermittently early in the pandemic, the select committee continued to hold public hearings virtually, along with other parliamentary committees, and it helped fill the accountability gap. Nevertheless, the select committee has faced difficulty in gaining access to the Government’s underlying modelling and assumptions for its response package, which prevents the committee from doing its job fully.

The Survey found some weaknesses in accountability of Australia’s COVID-19 fiscal response. First, no additional funding was provided to the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), despite the scale of expansion in government spending during the pandemic. In fact, government funding to the ANAO had declined in the 2020-21 budget.

Second, public participation opportunities were reduced to nil regarding the early response to the pandemic. Public consultation resumed only when the 2020-21 pre-budget submissions reopened in July.

Third, there was no gender impact assessment, and no release of gender disaggregated data, by the Government about the impact of either the pandemic or the Government’s fiscal response. This quickly became a problem as evidence began to appear suggesting women were affected disproportionately by the pandemic. The Government was criticised for failing to take into account the gender impact, for example on care and work challenges, in its response to the pandemic.

The Government has addressed some of these gaps, but challenges remain

The IBP study was completed in January 2021 and there has been some further developments since then.

In the 2021-22 budget in May, the Federal Government has finally reversed the ANAO’s budget cuts by allocating an extra $61.5 million over four years which would enable the audit office to take on more staff and conduct more performance audits post-pandemic.

There has also been more focus on women’s needs in the 2021-22 budget and the Government has brought back the Women’s Budget Statement as part of the budget papers. However, we are yet to see whether it will lead to substantial changes through incorporating gender responsive budgeting into the budget process and making such analysis publicly accessible.

Disappointingly, some innovations that arose during the COVID-19 fiscal response, including the release of the pre-budget statement, have not been integrated into the budget process in the lead up to the 2021-22 budget.

The IBP global study demonstrates how difficult it is to achieve and maintain budget transparency in a crisis. Continued vigilance to support fiscal transparency is needed as governments roll out economic, procurement and fiscal responses to the pandemic roll in coming years.

Recent Comments