Politicians often invoke the word “reform” to convey the significance, or gravitas, of a particular policy change they are proposing.

However, the tax policies implemented over the six years of the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison government should be more aptly described as: no reform, lots of tinkering, two blunders and some lost opportunities.

To be fair to the leaders of the Coalition, both Abbott and Turnbull began their prime ministerships professing a large appetite for tax reform.

In opposition Abbott and his treasury spokesman Joe Hockey had promised a major inquiry. Hockey said it would pick up where Labor’s Henry Tax Review left off:

We thought the Henry Tax Review was going to be a proper process. Now, that has obviously been an abject failure. We’ve said – Tony Abbott announced in Budget and reply speech – we will have a proper process for proper tax reform, and whatever comes out of that process, which will be a white paper, we will take to a subsequent election, seeking the mandate of the Australian people – their approval.

Treasury’s Re:think tax discussion paper, which is as far as the tax white paper process got. Source: Commonwealth Treasury

Treasury’s Re:think tax discussion paper, which is as far as the tax white paper process got. Source: Commonwealth Treasury

It got as far as a discussion paper, seeking submissions.

When Turnbull assumed the leadership, the draft white paper, which would have followed the discussion paper, was scuttled, and the process ended.

Tinkering…

Instead what resulted were marginal changes to personal income tax. One of the brackets was expanded and a new low and middle income tax offset was added.

Marginal changes to superannuation tax further added to the complexity of the tax system as a whole. The current superannuation system disproportionately rewards higher income earners because most contributions are taxed at the same low rate (15%) regardless of the taxpayers’ income tax rate.

The Coalition’s response was to apply a 30% tax on contributions for those earning $250,000 or more (down from the previous threshold of $300,000) and to cut the cap on concessional contributions from $30,000 ($35,000 for those aged 49 and over) to $25,000. And it capped at $1.6 million the amount that could be transferred into the “retirement phase” where fund earnings in retirement were exempt from tax.

It made the system much more complex, and it could have been done more simply, perhaps by reimposing tax on super earnings in retirement (at a low rate) or by taxing by contributions at a standard discount to taxpayers at a marginal rate, as recommended by the 2009 Henry Tax Review.

Alongside these marginal changes, there was also a failed attempt to cut the company tax rate (only the tax rates for small companies were cut) and a muddled discussion about the progressivity of the income tax system.

All in all, many a tinker, but no reform.

Blunders…

Human-induced climate change is compromising the sustainability of our planet. The only way to solve it is by changing incentives using the economic toolkit at our disposal. The Carbon Tax was a good tax. It shifted the costs of pollution onto those who created it, instead of subsidising processes that damaged the environment.

No solution to climate change is possible without corrective taxes.

At some point we’ll have to climb that mountain again, assuming the mountain is not underwater before politicians come to their senses.

The repeal of the Minerals Resource Rent Tax was also a step backwards. By taxing rents (excess profits) instead of profits, it avoided the disincentives created by traditional company taxes. And, it was a good example of the kind of taxes that could eventually replace or supplement company tax.

…and lost opportunities

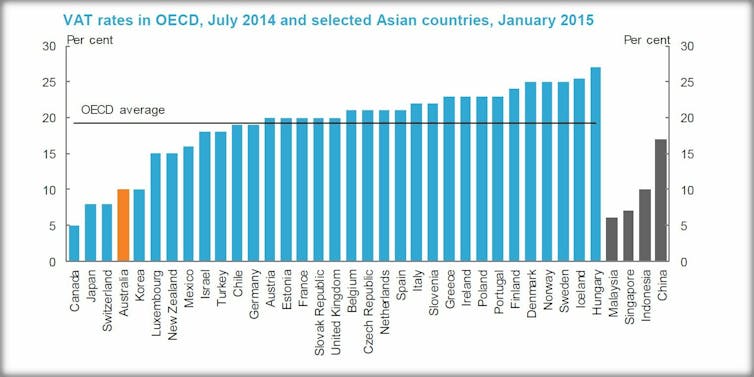

Changing the GST could have ensured at least one significant contribution to overall tax reform. At 10%, the rate is relatively low by international standards and applies to a shrinking share of spending, as more and more of our money is spent in places or on goods that aren’t taxed.

Value-added (GST) tax rates in OECD and selected Asian countries. Re:think, Treasury tax discussion paper, March 2015

Value-added (GST) tax rates in OECD and selected Asian countries. Re:think, Treasury tax discussion paper, March 2015

These factors, combined with the fact that GST is difficult to evade and less costly to administer, suggest that broadening the base is low hanging fruit on the tax reform tree, ripe for picking.

Instead, it may as well be forbidden fruit from the Garden of Eden. We’ve gone in the wrong direction by adding even more exemptions and cutting short talk of increasing the rate.

The failed debate on company tax cuts was another missed opportunity.

What remains is a system that applies different rates to different company sizes, one of few remaining dividend imputation systems in the world, and no discussion about the sustainability of corporate income tax revenue in the future.

All up, the government’s approach over the past six years has largely been piecemeal. It also managed to dismantle two of the most significant tax reforms that could have contributed to a more sustainable tax base in the long run.

Would Labor be better?

It remains to be seen whether a Labor government will be able to achieve more. Some of the party’s proposed changes, such as the treatment of capital gains, head in the right direction, but what it is offering falls short of comprehensive reform.

At the same time, many of its proposed changes will add additional complexity, fail to account for interactions within the entire tax system and use tax exemptions to reach goals that could be better achieved with payments.

Many an international tax reform was engendered by crisis, so there’s hope, of a sort. The opportunity still remains to get in early before weaknesses inherent in the current system become grossly apparent.

What we’ve got is unfair and its complexity rewards those with the resources to pay to understand and exploit it. It is overly reliant on income and company tax in place of indirect taxes, like consumption tax, and it tries to achieve too many disparate objectives, without consideration for the workings of the family and social security payments system.

There is much scope to improve things. What we need most are fearless leaders, from all sides of the political spectrum, who treat comprehensive tax reform as important and can work together to achieve it.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. This article is part of a series examining the Coalition government’s record on key issues while in power and what Labor is promising if it wins the 2019 federal election.

Recent Comments