Large organisations are important for a country’s state budget. A considerable proportion of these organisations pay corporate income tax, but they also act as withholding agents for various taxes and levies such as payroll tax, value added tax, and taxes on certain cross-border payments like dividends, royalties, and interest. In recent years, large organisations have increasingly been criticised for avoiding taxes, and there is growing public and political indignation about the use of aggressive tax planning arrangements by some of these organisations.

Given the importance of corporate tax compliance, empirical research regarding large organisations’ tax behaviour is surprisingly scarce. The few studies that have been conducted generally focus on economic determinants of corporate tax compliance, such as tax rates, audit probabilities, and other deterrent factors. Research concerning private taxpayers, self-employed individuals and small business owners, however, shows that sociological and psychological factors are at least as important as economic factors in explaining differences in tax compliance (for example, Hartner, Rechberger, Kirchler, & Schabmann, 2011).

This insight has also been noted by regulators. Whereas regulators, in general, have traditionally embraced a power-based regulatory strategy built on economic deterrence, this approach now seems to be giving way to a normative, trust-based strategy utilising persuasion and moral appeal. The effectiveness of these two regulatory strategies has been the subject of scholarly debate, but the emerging consensus seems to be that a mix of both strategies is optimal, and that the use of power or trust-based regulatory instruments by tax authorities should depend on the motives (or motivational postures) of taxpayers. This consensus is largely based on studies concerning the tax behaviour of individuals. However, very few empirical studies have examined the effectiveness of the two strategies (and their combination) in supporting tax compliance by large organisations.

We present the results of a study that empirically tests the roles of power and trust as determinants of corporate tax compliance. While power has received some attention regarding corporate tax compliance, the role of trust and the interaction between power and trust have not. A better understanding of the factors that determine tax compliance by large organisations may contribute to improved regulatory strategies for such organisations, which could be highly relevant for tax authorities. Indeed, many regulators are in the process of changing their large organisation tax compliance strategy towards a more trust-based approach, such as the so-called cooperative compliance strategies. In addition, the OECD encourages tax authorities to combine power and trust-based approaches through their compliance risk management approach. By exploring the role of trust and power in corporate tax compliance, this study provides new evidence on the ongoing discussion regarding the effectiveness of employing trust and power-based regulatory strategies.

The Slippery Slope Framework

To study the role of trust and power in a setting of large organisations, we build from a theoretical framework known as the ‘Slippery Slope Framework’ (SSF). The framework was introduced by Kirchler, Hoelzl and Wahl (2008) and integrates empirical findings from economics, sociology and psychology. The Slippery Slope Framework identifies two central factors that influence taxpayer compliance, namely the perceived power of, and trust in, tax authorities. The power of tax authorities is defined as taxpayers’ perception of tax authorities’ capacity to detect and punish tax crimes. Trust in tax authorities is the general opinion of individuals and social groups that tax authorities are benevolent and work beneficially for the common good. While both factors can stimulate compliance, the quality of compliance can range from enforced compliance to voluntary compliance.

The Slippery Slope Framework postulates that a deterrence-based regulatory strategy increases the perceived power of tax authorities and results in enforced compliance, whereas a trust-based regulatory strategy posits that increasing trust in tax authorities results in voluntary compliance. Voluntary compliance reflects a willingness to comply out of a sense of moral obligation, while enforced compliance reflects a feeling of being coerced to comply. Both voluntary and enforced compliance are assumed to contribute to tax compliance in general. The framework also emphasises the interaction between power and trust, postulating that the effects of power and trust depend on each other.

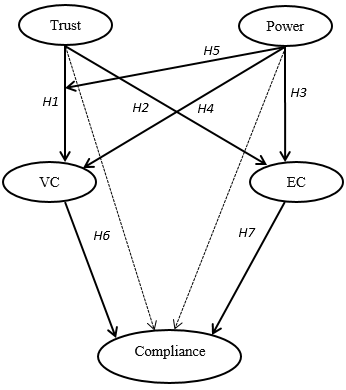

Based on descriptions of the Slippery Slope Framework, we construct the following theoretical model (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Visualisation of the hypotheses

VC=voluntary compliance, EC=enforced compliance

This model visualises the seven relationships we examine. Firstly, trust is considered the main factor in explaining voluntary tax compliance. Secondly, a trust-based strategy may elicit opportunistic behaviour by taxpayers who might strategically abuse the trust put in them. Thus, when trust increases, the feeling that one is forced to pay taxes might decrease. Thirdly, when taxpayers anticipate the potential use of power by tax authorities, enforced compliance increases. Fourthly, when power is perceived to be oppressive (as opposed to legitimate), it might decrease voluntary compliance. Fifthly, the perceived power of tax authorities can affect the relationship between trust and voluntary compliance. More specifically, we expect low power to attenuate the positive relationship between trust and voluntary compliance. Sixthly and seventhly, voluntary compliance and enforced compliance intentions are positively related to actual tax compliance.

The Survey

The data for our study were collected in 2014 through a survey among senior staff responsible for tax matters of large organisations in the Netherlands—for instance, tax director, head of tax, chief financial officer or controller. The survey data was collected as part of a larger research project of the Netherlands Tax and Customs Administration (NTCA), which aims to shed light on the relationship between NTCA’s regulatory strategy for large organisations and tax compliance. The administration of the survey was commissioned to an external research agency. The research population is the group of about 8,500 large organisations in the Netherlands, from which a sample of 350 organisations was drawn. A total of 271 out of the 350 selected organisations completed the survey (a response rate of 77 per cent).

Our dependent variable is corporate tax compliance. Because compliance is difficult to measure unambiguously, we use a series of proxies for (non-)compliance that are intended to cover the full spectrum of different meanings attached to the term. This includes tax minimisation (“My organisation explores the limits of tax legislation”), which captures the more legalistically defined end of the spectrum, and tax aggressiveness (“My organisation uses risky tax structures”), which should cover the other end. In addition to these two items, we also use a general self-reported measure of tax compliance, consisting of three items: timely filing of tax returns, timely payment of due taxes, and reporting complete and accurate information.

Findings

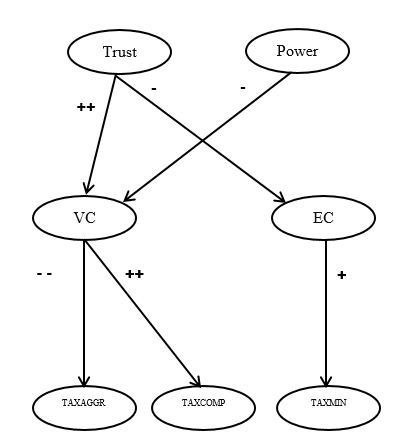

Figure 2 below shows the main findings of this study.

Figure 2: Significant results of the structural equation model

– = significant negative effect, p<.05

— = highly significant negative effect, p<.01

+ = significant positive effect, p<.05

++ = highly significant positive effect, p<.01

VC=voluntary compliance, EC=enforced compliance, TAXCOMP= self-reported tax compliance, TAXAGGR=tax aggressiveness, TAXMIN=tax minimisation

In line with studies on the tax behaviour of individual taxpayers, we conclude that trust and power also play an important role in the tax compliance behaviour of large organisations. We find a positive relationship between trust and voluntary compliance and a negative relationship between trust and enforced compliance. Furthermore, we observe a negative relationship between power and voluntary compliance.

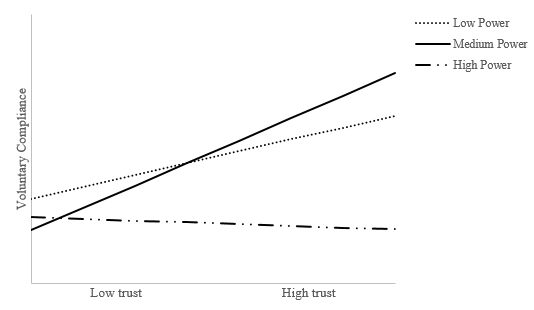

Contrary to expectations, we do not find a relationship between power and enforced compliance. We conclude that greater perceived power does not seem to result in more enforced compliance, but that it does in fact lead to less voluntary compliance. To test the moderating effect of power on the relationship between trust and voluntary compliance, we assign the large organisations in our study to a low (n=182), medium (n=55) or high (n=34) perceived power group. Results of this additional analysis (see Figure 3) support the notion that the use of power attenuates the positive contribution of trust upon compliance.

Figure 3: The moderating effect of power

A more complex picture

Our findings on the relationship between voluntary and enforced compliance suggest a more complex picture than found in earlier studies of individuals and small businesses.

In our study, voluntary compliance is positively related to self-reported tax compliance and negatively associated with tax aggressiveness, both as expected. However, we do not find a relationship between voluntary compliance and tax minimisation, while enforced compliance is positively associated with tax minimisation—although this latter association cannot be observed in an additional analysis that excludes not-for-profit organisations from the sample.

The lack of an association between enforced compliance and tax compliance measures seems to imply that being or feeling forced to comply is unrelated to corporate tax compliance. Possibly, the separation of ownership and control within most large organisations weakens potential effects of enforced compliance on tax compliance. Often, management gains from tax non-compliance, while possible losses (due to detection and punishment by the tax authorities) will be borne by the owners. Management may also anticipate leaving the organisation before the non-compliance is detected.

We conclude that these results could be interpreted as supporting the change by tax authorities worldwide towards trust-based regulatory activities, which have been adopted as a way to stimulate corporate tax compliance by large organisations. Further exploration of the potential effects of these trust-based regulatory activities, such as cooperative compliance, on the tax compliance behaviour of large organisations is an important avenue for future research.

This blog post is based on our paper: ‘Corporate tax compliance: Is a change towards trust-based tax strategies justified?’, Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, vol. 32, September 2018, pp. 3-16.

Recent Comments