Taxes create a number of incentives that lead households and firms to modify their economic decisions through evasion, avoidance, or real responses, in order to minimise the effect of a tax change or simply to reduce their tax bill. All these behavioural responses have an impact on reported income and, hence, on tax revenue. Therefore, the magnitude of these responses has implications for the design of the tax system and the revenue-raising capacity of the tax structure. However, understanding the effect of tax rates on tax revenues requires a measure that captures all of these potential responses to taxation. To address this, public finance economists have focused their attention on estimating the elasticity of behaviour with respect to taxation.

Sanz-Sanz et al. (2015) identify three generations of studies on tax elasticity. A first generation focused on the impact of income taxes on the number of hours worked and the decision to participate in the labour market. However, this first generation omits other aspects of individual behaviour and other dimensions of labour supply such as effort and ability. It was not until the seminal studies of Martin Feldstein that a new parameter emerged in the public economic literature, the elasticity of taxable income (ETI), and gave rise to the second generation. Feldstein’s main contribution was to consider labour supply as only one of the potential responses to income taxation. The ETI is a single measure that captures all behavioural responses resulting from a marginal change in taxation.

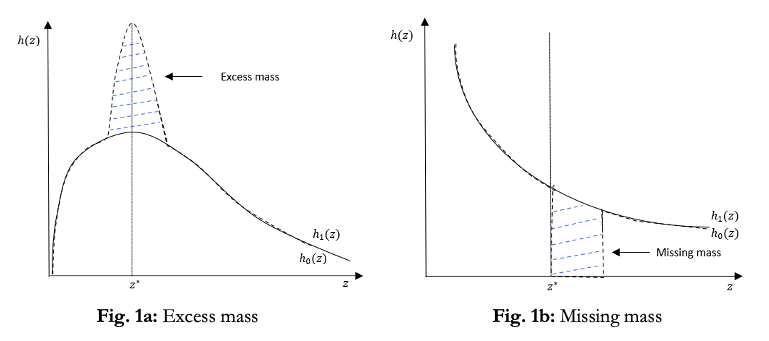

In recent years, a third generation of studies has moved towards examining the precise nature of individual responses, taking advantage of the development of more robust econometric methods and the availability of administrative tax data. One strand of this literature uses a non-parametric method—called the bunching approach—to estimate the ETI. This approach was initially proposed by Saez (2010) and then modified by Chetty et al. (2011). It is a visual technique that relies on identifying agglomerations (or bunchings) in the distribution of taxable income. The discrete jump of marginal tax rates at bracket cut-offs (or kinks) introduces taxpayers’ incentive to move from a point above the cut-off to a point just below it by reducing taxable income through legal or illegal channels. Therefore, looking for bunching around kink points provides evidence of behavioural responses to taxation, and more importantly, based on Saez’s (2010) work, the ETI can be inferred from the amount of excess bunching (see Figure 1).

Note: Figures 1a and 1b illustrate excess mass and missing mass using empirical densitites, where, is earnings and is the kink point.

Spanish personal income tax

Over the past decade, there has been a growing trend of using this approach to estimate the ETI, with a particular focus on the behavioural responses of taxpayers in higher income brackets. Our study aims to fill this gap by providing evidence of low-income taxpayers’ responses to the personal income tax and the mechanisms underlying these responses. We rely on the bunching approach and a large administrative tax return dataset on taxable incomes for the Spanish taxpayer population over the period 2008 to 2017. We focus on the first two tax brackets of the Spanish personal income tax. These brackets are of particular interest as they comprise more than half of all individual taxpayers. Moreover, the first bracket is where tax liability starts, and the change in the net-of-tax rate is the largest (26 percentage points).

The Spanish personal income tax is a progressive tax with tax rates that jump up at certain thresholds, creating kinks in the tax schedule. The tax has been subject to several changes over the 2008–2017 period. This study explores two major reforms introduced during this period, the 2012 and 2015 tax reforms, carried out by the government in the context of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis. The 2012 tax reform increased the marginal tax rates for all brackets and introduced two marginal rates at the top, leaving the tax schedule with seven tax brackets. The 2015 reform, among other tax changes, reduced all income tax rates and income thresholds (from seven to five) and modified a critical deduction to labour income. These two reforms intensified the progressivity of the tax and exacerbated the incentives for the strategic behaviour of taxpayers.

Behavioural responses of low-income earners

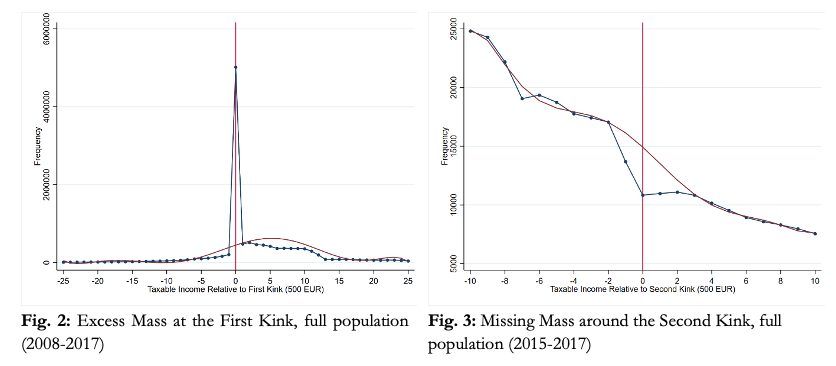

The results provide strong evidence of behavioural responses to taxation by low-income earners. We find significant bunching at the first kink of b = 8.9; that is, the number of individuals around the kink is 890 times the number of individuals that would have been present in the absence of the kink (see Figure 2). This bunching yields an implied elasticity of e = 0.7. We also find a non-negligible missing mass around the second tax kink of m = 0.42, which yields an implied elasticity of e = 0.26. This hole in the taxable income distribution corresponds to a loss of wage earners of 42% compared to the average counterfactual distribution (see Fig. 3).

The 2012 and 2015 tax reforms allowed investigation of the dynamics of bunching. We observe that bunching grows over the period considered, especially in years soon after the reforms. In non-reform years (2008 to 2010), bunching is between 6.43 and 6.69, and steadily increases to 8.56 following the 2012 tax reform. Bunching jumps considerably in 2015 to 10.93 and continues to increase to 11.58 in 2017. The elasticity follows a similar pattern; it grows from 0.47 in 2008 to 0.59 in 2012 and 1.10 in 2017. We only detect missing mass in the period 2015-2017. In 2015, the estimated missing mass was 0.90, in 2016 it was 0.63, and in 2017 it was 0.52, which implies elasticities of 0.57, 0.40, and 0.33, respectively.

Heterogeneity in responses

We examine heterogeneity in behavioural responses by dividing the population into several groups according to their income source, gender, place of residence, age, marital status, tax filing status, number of children, and number of ascendants. As for the first tax kink, our study finds that the most responsive taxpayers are wage earners, older taxpayers, men, unmarried, joint filers, taxpayers without children, taxpayers with ascendants, and taxpayers living in wealthy regions. As for the second tax kink, the most sensitive taxpayers are wage earners, young taxpayers, women, unmarried, single filers, taxpayers without children, taxpayers with ascendants, and taxpayers living in poor regions.

The presence of significant heterogeneity in responses among certain groups confirms that in Spain, the composition of the household plays a crucial role in determining tax liability.

Anatomy of behavioural responses

Taxpayers’ tax liability is influenced by numerous factors, including provisions in income tax laws, statutory tax rates, and individual circumstances. The Spanish personal income tax system has three significant provisions that have a considerable impact on taxable income: standard deductions, itemised deductions, and the allowance for past negative taxable income. Our study shows that Spanish taxpayers do use these three provisions to lower their taxable income and cluster around the first tax threshold. This result is especially detected among wage earners. Before considering any deduction, there is no sign of bunching at the first kink in the income distribution for wage earners. Since taxable income is determined by a combination of several components, we cannot attribute bunching at the first kink point solely to deductions. Nevertheless, it suggests that these deductions play a fundamental role in explaining the bunching behaviour of wage earners.

Further explorations of the potential mechanisms behind missing mass confirm that the phase-out region introduced in the standard deduction for labour income in 2015 may have discouraged wage earners from reporting income in this region. The tax reform of 2015 raised the phase-out rate from 0.35 to 1.15, meaning that from that year onwards, the deduction is phased out at a rate of 22 to 28 cents per euro of net labour income between €11,250 and €14,450. In other words, if a taxpayer in the phase-out region earns an extra euro of net labour income, their deduction would decrease by 22 to 28 cents. This modification makes this region undesirable for wage earners who respond by not locating themselves there. Indeed, this region coincides with the location of the missing mass.

Pingback: Statutory vs. Effective Tax Rates in Europe - Financial Contracting