The legislation which applies Australia’s capital gains tax (CGT) regime to partnership assets is unusual in its design. Importantly, it diverges from the general law, namely the principles of the common law and equity, by treating partners as though they hold fractional interests in the assets of their partnership.

This post will consider the nature and implications of this inconsistency in the law in three parts. First, it will explore how the legislation underpinning Australia’s CGT regime diverges from the general law. Second, it will argue that this aspect of the CGT regime’s design has led to imprecision in the law that calls for amendment. Finally, reforms to the legislation which governs the regime will be proposed.

Divergence between the CGT regime and partnership law

Australia’s CGT regime concerning partnership assets is built around sections 106-5 and 108-5 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (ITAA 1997).

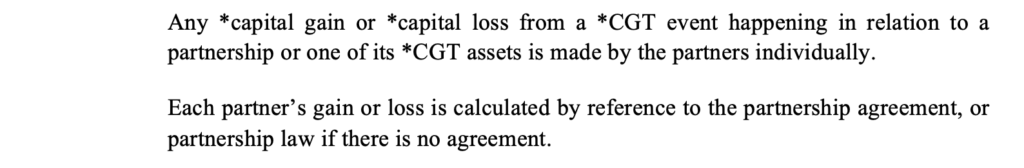

Section 106-5(1) provides:

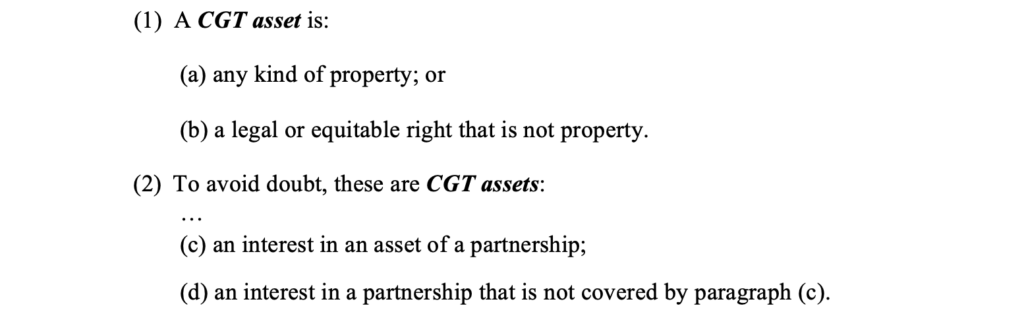

Section 108-5 of the ITAA 1997 relevantly provides:

Despite section 108-5(2)(c) referring to interests “in an asset of a partnership”, it is well recognised that partners ordinarily hold no such interests under general law.

In Commissioner of State Revenue v Rojoda Pty Ltd (2020), a majority of the High Court of Australia observed at [21] that the interest held by partners in respect of partnership assets “is not an interest in any particular asset but is an indefinite and fluctuating interest in relation to the assets”. The majority confirmed that the interest in fact held by partners is merely a right to their share of the net proceeds from the sale of each asset upon the completion of the winding up of the partnership (at [33]).

As noted by the Full Court of the Federal Court at [19] of Hedges v Commissioner of Taxation (2023) (Hedges): “unlike the position at general law, the capital gains tax provisions are drafted on the basis that each partner has an interest in each partnership asset.”

Accordingly, the ITAA 1997 employs a legal fiction in order to make partners responsible for the CGT consequences of capital gains and losses on partnership assets. That is, its provisions intend that for CGT purposes partners be deemed to hold a fractional interest in individual partnership assets.

Imprecision in the CGT regime

As Graeme Cooper observes, imprecision in tax law “leads to obvious problems, both social and economic” including that “imprecise rules do not set out rights and obligations clearly” and mean “a heightened need for advisors, which adds to the deadweight cost of the tax”.

There is demonstrable imprecision in the terminology used in section 108-5(2)(c) of the ITAA 1997. It makes little sense to refer to a partner’s “interest in an asset of a partnership” when prior to dissolution partners do not hold any quantifiable interest in individual partnership assets. Further, the fact that a legal fiction is being employed is not stated explicitly. Problematically, it is left to the reader to understand that the legislation must be interpreted this way.

This drafting is made even more opaque by the use of a second (and contradictory) legal fiction in section 108-5(2)(d). As noted by N Augoustinos[1], section 108-5(2)(d) draws upon a fictional view of a partnership as an entity in which the partners hold an interest, making this provision a strange juxtaposition with section 108-5(2)(c), which looks to the partners’ supposed interest in the partnership assets.

Even greater problems of uncertainty arise when section 106-5(1) is considered.

Pursuant to section 106-5, a partner’s capital gain or loss upon a CGT event in respect of a partnership asset is to be “calculated by reference to the partnership agreement, or partnership law if there is no agreement.” In Hedges (at [25]), the Full Court of the Federal Court observed that the reference to “partnership law” in section 106-5(1) “must be a reference to the general law of partnership”. However, as established above, a partner holds no fractional interest in a partnership asset under the general law.

Proposed reforms

There are three key ways in which much of the imprecision in the CGT regime could be corrected.

First, section 106-5 could be made clearer by stating explicitly that a partner’s gain or loss for CGT purposes is calculated by reference to the partner’s proportionate share in asset surpluses at the time of disposal and after payment of partnership debts and liabilities.

Second, this provision could adopt explicit rules for apportioning a partner’s share of an asset surplus. A possible model for such rules is found in the practice of the United Kingdom. There, a number of alternate methods for allocating the surplus resulting from the disposal of a partnership asset have been recognised by His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs.

If the surplus is allocated among the partners, it is ordinarily attributed using the actual destination of the proceeds in the partnership accounts (with regard also paid to any agreement outside of the partnership accounts). If the surplus is not allocated among the partners, the ordinary profit ratio is considered instead.

Third, section 108-5(2)(c) could be made more precise by stating that a partner is deemed to hold an interest in each asset of their partnership in proportion to their interest in the surplus capital of the partnership upon termination.

Conclusion

Sections 106-5 and 108-5(2) of the ITAA 1997 are ripe to be reformed. If the ITAA 1997 is to continue to deem partners to hold fractional interests in partnership assets for CGT purposes, this should be done with technical precision.

Though reforms of this kind would add to the length of sections 106-5 and 108-5(2), they would materially improve the clarity and conceptual coherence of these provisions. Until such changes are made, the inconsistency in the law created by the current CGT regime will continue to obfuscate the law’s meaning and application.

This post summarises key aspects of the article ‘The Application of Capital Gains Tax to Partnership Assets: Challenges and Reform’, published in volume 25(1) of the Journal of Australian Taxation.

[1] N Augoustinos, ‘Partnerships and CGT: An International Comparative Analysis’ (1993) 1(3) Taxation in Australia Red Edition 126, 133

This is an amusing illustration of the truth that “tax reform” proceeds from anomaly through inequity to further anomaly and further inequity.

Rather than tax reform we need wholesale tax repeal.