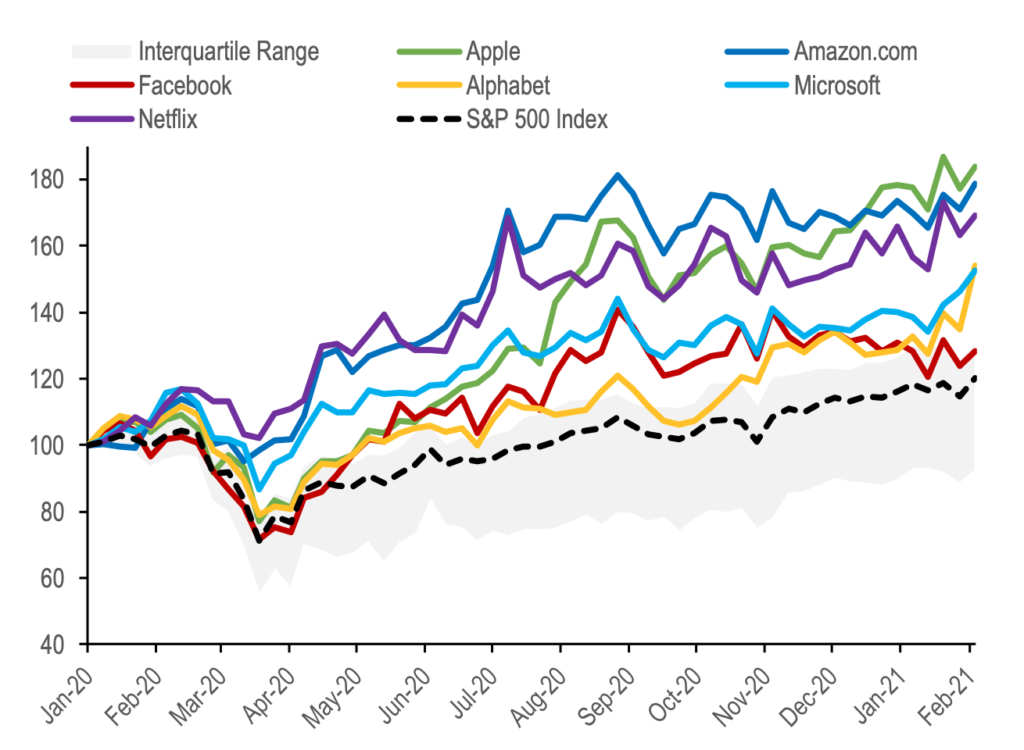

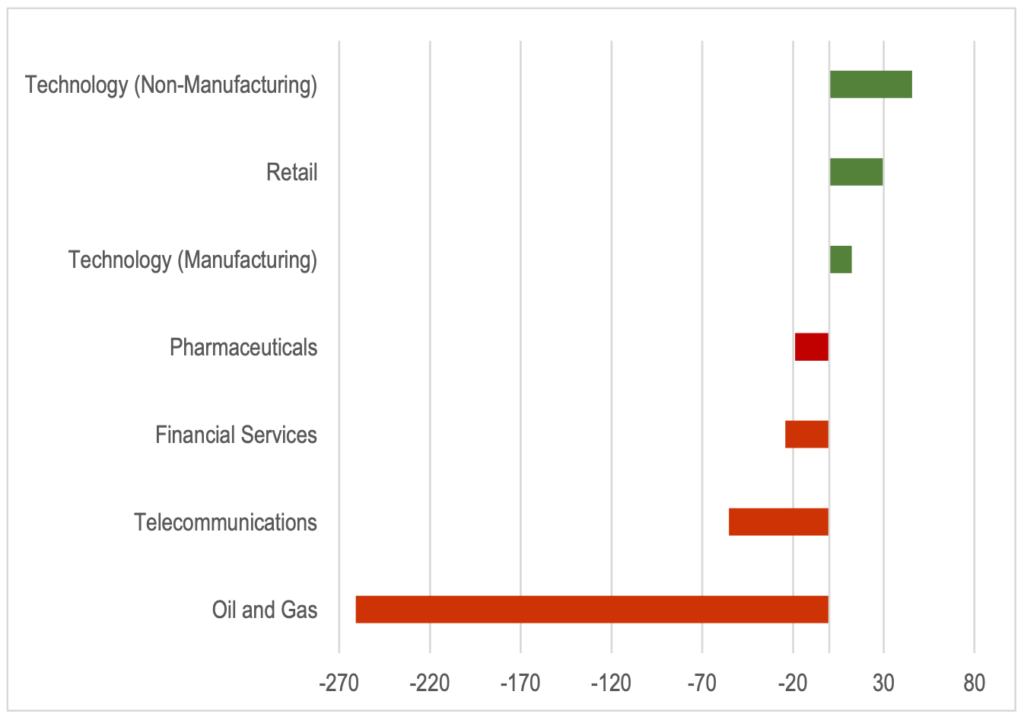

Digitalisation continues to change the way we consume, do business, and interact. Since almost all businesses are digitalised to some extent, identifying and isolating the so-called ‘digital economy’ is fraught. Yet many have zeroed in on a few firms at the frontier, which have capitalised on first mover advantages and network externalities to boost profitability, secure market dominance, and become the world’s most highly-valued companies. At the same time, the COVID-19 containment measures have pushed even greater amounts of activity online. This shift has inevitably favoured those businesses whose digital services have become indispensable during the lockdowns (Figures 1 and 2).

Policymakers have increasingly come to feel that these businesses may not be paying their ‘fair’ share of taxes overall—given the profits they are generating—and that they are only required to pay minimal taxes, if any, in many of the countries in which they provide services. The largely unregulated rush by businesses to mine and capitalise on user data lies behind these views. Many governments claim that the information on personal habits and preferences harvested by these data-intensive businesses—which is then processed and monetised, for example, through advertising and product development—is generating significant value for them, without adequate compensation to the users.

Building on our recent IMF working paper, this blog explores the question of whether an ad-valorem royalty, calculated as a proportion of the value of user data—and collected by governments on behalf of their citizens—could help countries to efficiently mobilise significant revenue; and whether it is feasible.

Figure 1. U.S. Stock Market Performance

(Index: 100=Jan 3, 2020)

Sources: DataStream and IMF staff calculations.

Figure 2. 2020 Earnings by Sector

(Year-on-year percent change)

Sources: DataStream and IMF staff calculations. Note: Includes top 50 companies by market capitalisation. See our working paper for sectoral classification.

From database to data (as the) base

Just as commodities—such as oil—have value before they are transformed into final products, we can expect raw user data to have value to both the business collecting and processing it, as well as the individual that is unknowingly bartering with it to obtain the digital service. For the individual, this value would be the opportunity cost of maintaining their privacy.

Yet governments and businesses remain divided over if and how the value of user data should factor in the allocation of profits worldwide for tax purposes. For this to happen, the legal right to tax income derived from user data would have to be established, as well as an appropriate metric for valuing it. Discussions have been ongoing at the OECD over the last decade to reach agreement on the former within the context of the international corporate tax system, while the latter has yet to be broached.

User-based royalties

A royalty may provide a viable—if somewhat imperfect—alternative as long as the current system does not cede rights and attribute profits to market countries whose users are also now a source. Applying a royalty to some measure of the value of user data could allow all countries—not just those where businesses have physical presence—to share in the rents of data-intensive businesses.

Just as in the extractives industries, royalties can substitute when direct taxation of rents is difficult, especially where hard-to-value intangibles play a large role, or capacity is limited to monitor cost-based profit shifting. Royalties also do not require modification of permanent establishment rules or income tax treaties. Moreover, they are already used to charge for the right to use a business’ intellectual property, such as copyrights, patents, and trademarks.

The design of a royalty should adhere to some key principles:

A well-defined base. Determining the value of user data is key. However, this can depend on a variety of factors, such as purchasing power, national internet connectivity, vintage, and the value of privacy to individuals. To begin with, governments could focus on two dimensions of data, volume and depth, collected over a fixed time period (for example, in a month). Companies could be required to report on the number of users they are collecting data on (volume) and the range of attributes being captured about them (depth)—for example, names, ages, addresses, consumption histories, browsing histories, and so forth. Benchmark unit values could be established for each attribute through consultation with industry. And once this has happened, companies can be charged a monthly royalty on the value of their datasets.

Any company that goes further and sells the data they have collected or uses it to provide services to other businesses—for example, online advertisers using data in the provision of personalised advertising services—could then be subject to a second charge on the sales value of that data or the digital services. However, many of these services are also only possible because of the proprietary knowhow (for example, algorithms) used, not just the data. And so a proportion of the value of the service—allowing for deductions to reflect the costs of storage and processing—can be attributed to the underlying data and subject to a location-specific royalty in the country in which the advertisement is viewed.

In the transition to the use of such valuation methods, a presumptive option could be offered to data collecting businesses, to apply the royalty to the difference in a firm’s market value over the book value of its tangible assets. While this means that the value of data and the value of firm-specific knowhow would be both taxed, if given the choice between this measure and a data royalty, this approach might encourage firms to report the value of their data more accurately.

A broad base. Given the increasing range of businesses collecting personal data across the economy, a royalty on user data should cover all companies that collect it, for example, airlines, manufacturers (collecting data via the Internet of Things), retailers, and financial services providers. This would help ensure neutrality across digitalised activities and limit arbitrage opportunities and distortions. Recent proposals (see below) have instead singled out particular activities, which risks driving an inefficient wedge between arbitrarily categorised ‘digital’ and ‘non-digital’ activities. While conceptually the tax should apply to all, for practical reasons there may be a need to restrict the application of the royalty to those companies that collect data in a material way, through the use of thresholds (see below).

An appropriate rate. Some countries might choose to be ‘data liberal’, others may be more ‘privacy conscious’. The rate could be calibrated to reflect these preferences. However, in choosing revenues over profits as the base, royalties are less likely to tax only the pure economic rent and therefore risk distorting production or disincentivising investment. In setting the rate, policymakers should also be sensitive to the degree of pass-through to consumers, particularly in a monopolistic setting.

Carefully calibrated size and data use thresholds: Too high a threshold may result in the targeting of only a few highly data-intensive firms and could risk international retaliation; while too low a threshold could deter entry and risk-taking by small businesses. Safe harbour or deferral provisions for loss making firms may be desirable in the current crisis—while some digitalised businesses are seeing healthy profits, others (such as accommodation rental platforms) are struggling.

International Coordination: Without sufficient cross-country coordination, there is a risk of multiple claims over an individual’s data, especially where location and nationality do not coincide.

Recent proposals to tax the digital economy

Current proposals indeed take on the flavour of user-based royalties, albeit uncoordinated and focused on only a narrow subset of digital activities—such as advertising, intermediation services, and the sale of data—for companies over a high turnover threshold and using sales revenues as the tax base. To the extent that in some cases only foreign businesses are liable, some have argued that these royalties are in fact de facto tariffs on the import of digital services.

Examples include the digital services tax proposed by the European Commission, and subsequent uncoordinated variants proposed or enacted by countries, such as Brazil, France, India, Kenya, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Other countries (such as Chile, Hungary, and Uruguay) have opted for withholding taxes on payments for advertising and other specified digital services made by residents to non-resident companies.

Not much revenue… yet

While it may be too early to evaluate current proposals, revenue estimates included in national budgets appear to be relatively low, averaging just under 0.02 per cent of GDP in 2020. This suggests that the yields—as well as the perceived cost to highly-digitalised businesses—may be overstated. Therefore, it is possible that royalties—in their current and highly targeted form—are unlikely to provide the revenues that governments are hoping for to help fiscal consolidation and finance the recovery.

However, proper data valuation opens up the possibility of broadening the tax base and confronting the user value issue head on. After all, it is clear that users and their data are increasingly important for almost all businesses. And with this, the more valuable these taxes could become. A broad-based ad valorem royalty on the value of user data therefore could provide a much-needed addition to a country’s fiscal arsenal.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Further reading

Aslam, Aqib, and Alpa Shah. 2020. “Tec(h)tonic Shifts. Taxing the ‘Digital Economy’”. IMF Working Paper No. 20/76

Recent Comments