The term austerity indicates a policy of sizeable reduction of government deficits and stabilisation of government debt, achieved by means of spending cuts or tax increases. Discussions about the relative benefits and costs of the austerity policies have been toxic, often taking a very ideological, harsh, tone.

The anti-austerity front argues that austerity is counterproductive: it results in increases, rather than reductions, in the debt-over-GDP ratio, since it generates reductions in the denominator of this ratio which more than offset the gains in the numerator. The pro-austerity front emphasises the impact of expectations and confidence on government debt. Imagine a situation in which an economy is on an unsustainable path with an exploding public debt. Sooner or later a fiscal stabilisation has to occur. The longer this is postponed, the higher the taxes that will need to be raised or the spending to be cut in the future. When the stabilisation occurs, it removes the uncertainty about further delays, which would have increased even more the costs of the stabilisation.

The harsh discussion on the effects of austerity has distracted commentators and policymakers from the most policy relevant result, namely the enormous difference, on average, between expenditure-based and tax-based austerity plans. Our book “Austerity: When it Works and When it Doesn’t” discusses the theory and the evidence needed to more properly assess the consequences of the different types of austerity. This piece presents the findings from our book and its accompanying article.

The costs of austerity depend on the choice of channel

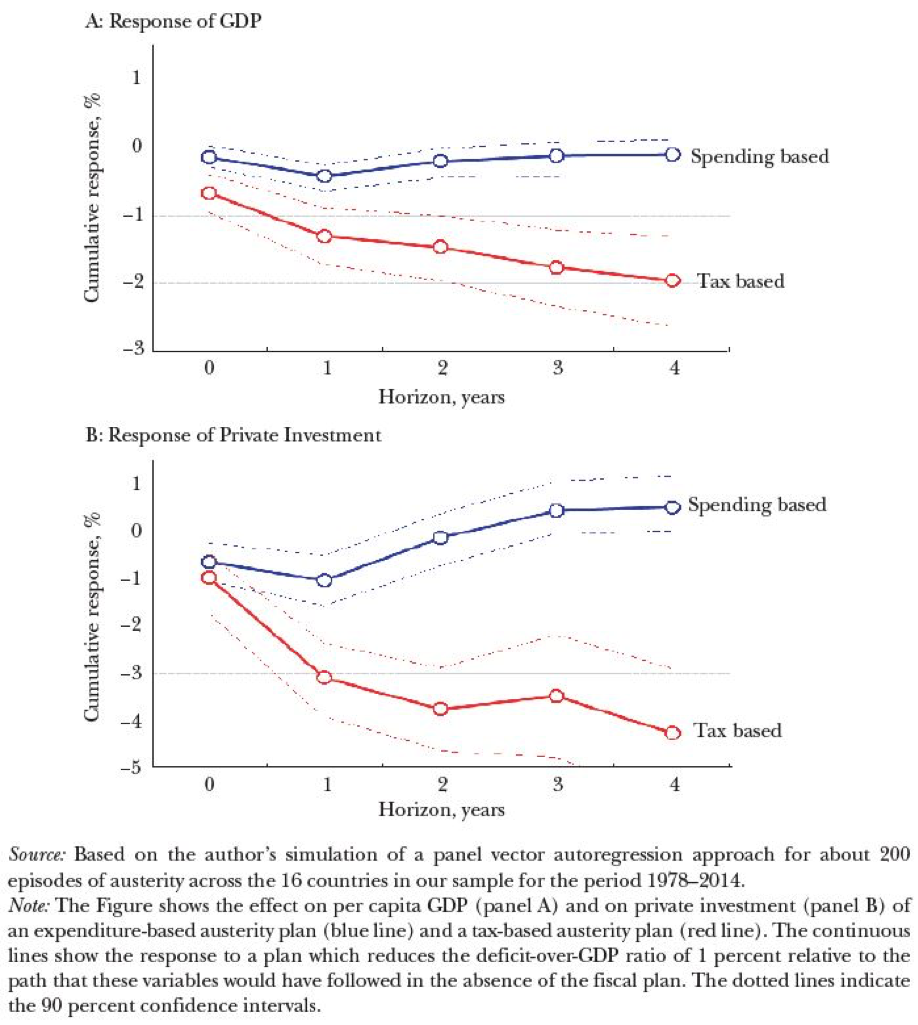

We find that spending-based austerity plans are remarkably less costly than tax-based plans. The former have, on average, a close to zero effect on output, and lead to a reduction of the debt over GDP ratio. Tax-based plans have the opposite effect: they cause large and long lasting recessions and do not lead to the stabilisation of the debt to GDP ratio. Two recent examples are the consolidations carried out by Ireland and Spain in response to the Eurozone crisis. The Spanish correction, which featured a larger share of tax hikes, markedly slowed the real GDP growth and did not result in a decline in the debt ratio. In Ireland instead, the spending-based correction had little output costs and led to a sharp decline in debt.

The empirical analysis of the macroeconomic effect of different types of austerity is crucial. To this end, one should start from the data. We have documented in detail close to 200 austerity plans carried out in 16 OECD economies (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Spain, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Portugal, United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States) from the late 1970s to 2014. To reconstruct these plans, we have consulted original documents—some produced by national authorities, some produced by organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the European Commission—concerning about 3,500 individual fiscal measures.

The second step is the proper modelling of fiscal actions. When legislatures decide to launch a fiscal consolidation program, this rarely consists of isolated shifts in this or that tax, or in this or that spending item. Instead, what is adopted is typically a multi-year plan with the objective of reducing the budget deficit by a certain amount every year. To the extent that expectations matter for the planning of consumers and investors, the multi-year nature of a fiscal adjustment, and the announcements that come with it, matter for their economic effects.

Third, the effect of different plans on the economy should be assessed. We document a sharp difference between adjustment plans based mostly on tax increases and plans based mostly on expenditure reductions (see Figure 1). This finding suggests that there is no “austerity” as such: the effects of austerity policies are sharply different depending on the way they are implemented.

Figure 1. The response to two different austerity plans

Assessing the evidence

In assessing the empirical evidence, we needed to overcome three major obstacles.

The first is the so-called “endogeneity” problem, namely the interaction between fiscal policy and output growth. Suppose you observe a reduction in the government deficit and an economic boom. It would be highly questionable to conclude that policies that reduced deficits have generated growth, as it could easily be the other way around. We address the endogeneity problem by considering only policy changes not motivated by the state of the business cycle, but rather by a desire to reduce deficits.

Second, once exogenous fiscal adjustments episodes have been identified, then the calculation of their impact on the economy requires the specification of an empirical model. An important trade-off emerges here: the simpler the model the easier to calculate the multipliers, but the simpler the model the more likely is that important relations among variables are missed. We adopt several models to assess the robustness of our empirical results.

Third, major episodes of austerity often are accompanied by changes in other policies: monetary policy; exchange rate movements; labour market reforms; regulation or deregulation of various product markets; tax reforms; and so on. In addition, austerity is sometimes adopted at times of crisis due to runaway debts, not in periods of business as usual. We assess explicitly the role of accompanying policies in the determination of the impact of austerity to conclude that the heterogeneous effects of tax-based and expenditure-based plans does not depend on different accompanying policies.

During 2010-11, the collapse of confidence in sovereign European debt and the explosion of interest rates on government bonds in some countries (Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal) led to a situation that was close to a debt-induced financial crisis. Could have the governments of these countries waited, postponing austerity to when the recession was over? Hard to say. We do not know what would have happened absent austerity. What we can say, however, is that even in these cases, namely when austerity policies are implemented during a recession, the differences between the two types of austerity is very relevant: tax-based austerity plans have been much more costly than spending-based plans.

Politicians do not necessarily lose elections

Contrary to common beliefs, the data do not show that politicians who implement austerity policies systematically lose the next elections. Presumably, when the need for austerity is well explained to the voters, and austerity is not too costly in terms of short run output losses, they can be successful.

In the 1990s, Canada implemented a successful package of large government cuts which, coupled with accommodating monetary policy and structural reforms, was expansionary. In the book, we document how since the 1993 elections almost all the contending parties accepted the need for such a reduction in government debt and deficit. In 2010, the Coalition government led by David Cameron in the United Kingdom responded to unsustainable and growing deficits with a program of large budget cuts. After this correction, the UK economy grew at respectable rates compared to the other major economies and proved the IMF predictions of a major recession wrong. Finally, and maybe most interestingly, the Irish government in its December 2009 Stability Programme Update was clear in acknowledging the unsuccessful effects of tax-based austerity. This in turn justified the adoption of a package of significant expenditure cuts.

Talking about “austerity” without distinction of how austerity is implemented does not make any sense. The composition of austerity plans is crucial to understand their effects on growth and fiscal sustainability.

Further reading: Alesina, A, Favero, C & Giavazzi, F 2019, ‘Effects of austerity: Expenditure- and tax-based approaches’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 141-162; Alesina, A, Favero, C & Giavazzi, F 2019, Austerity: When it works and when it doesn’t, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

As Modern Monetary Theory tells us, federal taxes in a sovereign currency issuing country, with a free floating exchange rate don’t fund spending. Spending under these circumstances is to balance the economy NOT a budget, therefore deficits and surpluses only become meaningful where there is utilised/unutilised resources like capital or labour in that economy. The history of public finance in the USA and Australia indicates that budget deficits are the norm not the exception. How does this sit with your understanding of how the financial system and the macroeconomy functions?