As we anticipate Budget 2018-19, coming up on 8 May, it is timely to examine Australia’s budget process. Australia has been a leader in good budget processes, but it is two decades since the Charter of Budget Honesty was enacted in 1998 and this reputation has faded. Public trust in government is at a low ebb, as polls suggest growing disillusionment among voters.

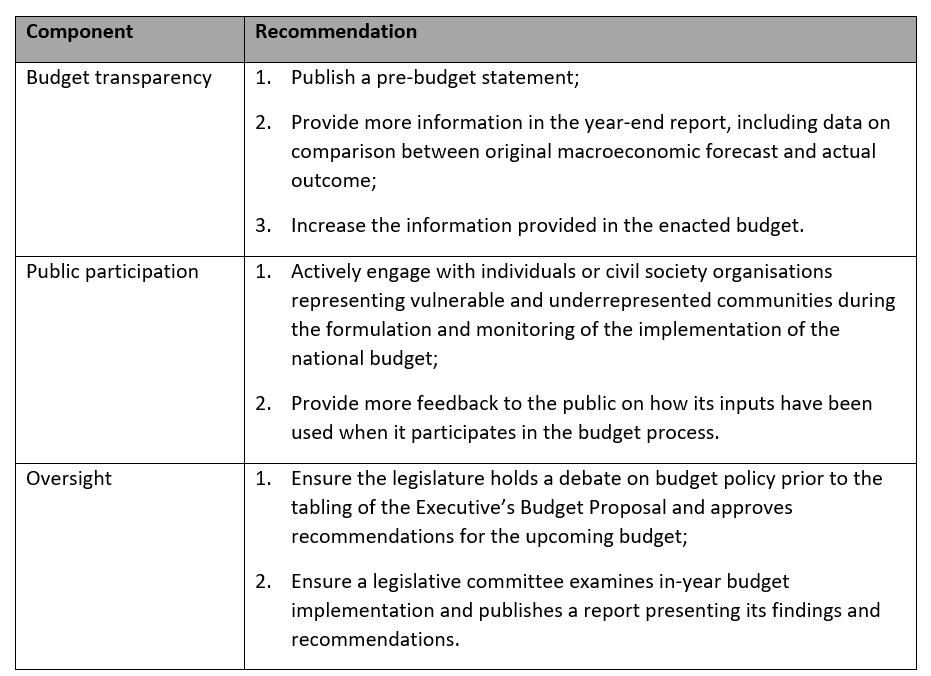

In Part 1, we presented the key findings from the Australian Open Budget Survey 2017. Australia scores well on budget transparency, yet there are gaps in the system. In this Part 2, we discuss the International Budget Partnership’s recommendations for reform of Australia’s budget process in the country summary report . Table 1 summarises the recommendations.

Table 1: OBS 2017 recommendations for Australia

Source: International Budget Partnership 2018

Plenty of financial information but a lack of distributional information

Australia performs strongly in terms of the financial information provided in the government’s budget proposal. But the OBI Survey confirms that distributional information is missing. The Australian budget does not break down the impact of taxes and expenditures, for example by gender, ethnicity, income or age, to illustrate the financial impacts of policies on different groups.

In the past, the budget contained “cameo” tables, which show the projected impact of policies in the real disposal incomes of different hypothetical families, but this practice ceased in the 2014-15 budget. In contrast, the United Kingdom includes a supplementary document in its budget to illustrate the distributional impact of tax and welfare changes on households.

Australia does not provide any analysis of the budget by gender. This is in contrast to the 1980s, when Australia was a pioneer in introducing gender budget analysis. The last Canadian budget places gender equality as a key focus of budget data, analysis and policy.

In Australia, the gap is now filled by civil society: the National Foundation for Australian Women has produced Gender Lens on the Budget reports since 2014-15. The Opposition also produces a women’s budget statement. This external analysis is important but it cannot by definition influence budget policy as it is formed and put together without access to internal government data.

More can be done to improve public understanding of budget information. Simpler and less technical budget documentation is only produced for the executive’s budget proposal and there is no attempt to identify what information the public really wants.

With full access to statistics and distributional modelling, the Treasury is capable of publishing detailed distributional analysis. It can also explain where dynamic effects, such as on work incentives or investment, should generate different results in future.

Realistic forecasting to connect economic, fiscal and equity goals

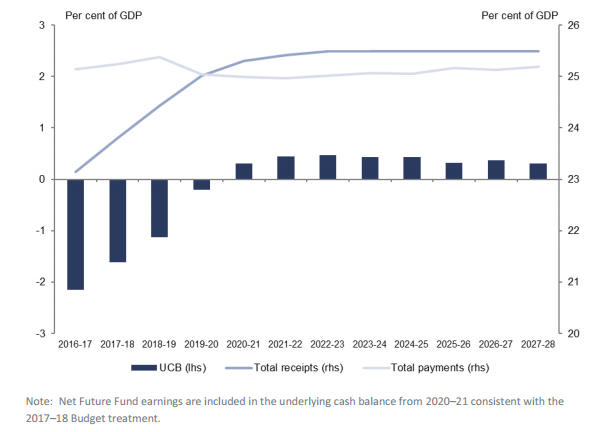

There have been questions about economic forecasting in Australia’s budget, particularly for government revenues . These assumptions lead to questions about fiscal forecasts, casting doubt on credibility of the “path to surplus” illustrated in the budget papers every year. This is the case, even though – as the Parliamentary Budget Office recently demonstrated – the path to surplus is consistent with credible economic assumptions.

Figure 1: Path to surplus – Commonwealth budget balance, per cent of GDP

Source: Parliamentary Budget Office 2017

The four year forward estimates which are central to the budget policy costings build on the same economic and fiscal assumptions and tend to bias policy and political decisions with an assumption of surplus in the out years.

With an eye to the longer term, the Intergenerational Report required every 5 years by the Charter is supposed to support reasoned debate about fiscal sustainability. But there was a widespread perception that the 2015 report was just another political document and some suggest that the model, goals and assumptions of the report need improving to support reasoned debate about long term budgeting, fiscal sustainability and intergenerational equity.

Inadequate public engagement and deliberation

Anticipating the budget, there have been the usual news stories about tax cuts and spending plans, as the Government drip-feeds key budget stories through press conferences or apparent leaks. But neither the Parliament, nor the Australian public is directly engaged in this pre-budget process.

Australia’s budget process does not meet minimum expectations of the latest Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency’s (GIFT) Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy. These ambitious principles pose a challenge to budget processes of all governments.

One key principle for public participation is Timeliness which recommends that the government should engage the public as early as possible when a range of policy options is still open.

It is true that pre-budget submissions have for many years been invited by the Treasury; individuals, businesses and community groups can submit proposals. In 2017-18 and 2018-2019, the Treasury began publishing those submissions where consent was given. But there is no feedback to those who submit proposals and no two-way engagement between the public and government officials.

Of course, as Parliamentary Budget Officer Jenny Wilkinson noted at the Australian launch of the Survey, in our democracy, informal avenues such as consultations held by parliamentarians with their constituents, are important and these are not captured by the Survey. Yet these are non-transparent and many view them as interest-based political lobbying.

Economic forecasts and anticipated revenue, expenditures, and debt for the coming fiscal year are available in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) report released in December each year. But the government does not release any pre-budget statement to Parliament or the public, unlike both New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

There should also be a systematic attempt by the government to engage vulnerable and underrepresented communities in the budget process. Although disadvantaged groups such as Indigenous Australians and the rural community are often the focus of budget announcements, the Survey finds no concrete and proactive steps to include them in the budget process.

Parliamentary oversight and engagement

There is room for the Parliament to improve engagement and oversight of budget implementation. Australia has no pre-budget parliamentary debate about budget priorities or broad fiscal strategies, without being tied to detailed funding allocation in the budget approval stage. In New Zealand the government must publish a Budget Policy Statement six to eight weeks before the budget, which is then debated by a parliamentary Committee.

There is also limited parliamentary oversight of implementation of the budget, and its outcomes. The budget outcomes report, required by the Charter and published in September after year-end, is hardly noticed by the public.

Budget transparency is a national and global challenge

It is clear from the Open Budget Survey findings that we can improve Australia’s budget transparency and accountability.

The Survey has limitations. It does not cover State and local governments, and its “one size fits all” approach does not recognise the nuances of Australia’s parliamentary democracy. It also does not give adequate credit for the important role of the Parliamentary Budget Officer in the last 5 years. There is scope to broaden the role of the PBO in budget oversight and engagement.

The global report of the OBI suggests that we cannot take budget transparency for granted. For the first time since the Open Budget Survey began over a decade ago, global progress toward greater transparency has stalled. The situation is worse in many developing countries, but even developed countries like Australia need to work to maintain and improve budget transparency and accountability to address growing scepticism and restore trust in government.

The Open Budget Survey 2017 findings are a wake up call and provide impetus for a debate in Australia about improvements to enhance budget transparency, participation and oversight.

Further readings: Australia country report | Global report | Rankings | Results by country | Data explorer

Open Budget Survey 2017 Part 1: How Transparent is the Australian Budget?

A Speech by the Parliamentary Budget Officer: Fiscal Transparency and the Parliamentary Budget Office, by Jenny Wilkinson

Podcast

Pingback: A Speech by the Parliamentary Budget Officer: Fiscal Transparency and the Parliamentary Budget Office - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Pingback: Open Budget Survey 2017 Part 1: How Transparent is the Australian Budget? - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Pingback: Budget Forum 2018: A Missed Opportunity for Enhancing Australia’s Budget Transparency on Distributional Information - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Pingback: Post-budget review | ANU-CPD POLICY DIALOGUE | May 2018 - Centre for Policy Development