Australians born in 2012 can expect to live about 33 years longer than those born 100 years earlier. However, only seven of these additional years are spent in the workforce. This longer life expectancy has driven policies to extend working life and increase retirement age. The current Australian policy, which has increased the eligibility for the pension from 65 to 67 by 2023, assumes that this improvement in longevity corresponds with an improvement in healthy life expectancy, hence older adults are able to work more. However, there is mixed evidence of health trends in Australia over the past two decades. Although some health outcomes are improving among older age groups, many are either stable or deteriorating. This raises a question of how health trends intersect with policy for older Australians aged from 50-70.

Our paper considers the interplay between older workers’ health and workforce participation rates over the past two decades when extended workforce participation has been actively encouraged by the Australian Government. The study aimed to describe the health profile of the older population over time using the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (HILDA) data. We also aimed to provide further insight into potential worsening of economic and health inequality amongst older people because for many living longer does not necessarily mean living with better health. We compared health and economic outcomes of the older people between 2001 and 2015, adjusting for some key population composition such as age, sex, ethnicity, education and equivalised household income.

Healthy life expectancy and longevity

An ageing population will certainly impact Australia’s employment, productivity, public finance, health care needs and services, all of which in turn, affect population health, economic growth and social equity.

The health of older Australians is generally seen as a costly problem that requires services, not as a key for economic success. Yet the health of older workers drives their ability to continue working; in Australia six out of ten workers reported involuntary retirement due to poor health. A conspicuous neglect of prevention policy means that chronic conditions are rapidly rising as people age, and this is widening economic disparities between those who can work and those who cannot.

There is a virtuous (or vicious) health-wealth cycle whereby less skilled and low-income Australians face worse health and more disability due to occupational hazards and physically demanding jobs. The financial benefits of employment assist older workers to maintain their good health or impede health deterioration due to their ability to pay for healthcare and other health-supportive resources. Net financial assets and superannuation protects older people’s health as they age further. Ill health leads to lower incomes and financial stress, increasing the risk of mortality. Gains in life and healthy life expectancy are disproportionately occurring among more affluent individuals.

In Australia, those in the highest socioeconomic group expect seven more years of full health for men and 4.8 more years for women than those in the lowest socioeconomic group. Thus, an increasing number of older, healthier and highly educated workers remaining employed and are able to earn income for longer. On the other hand, those with poorer health, less education and less earning capacity have less ability to prolong their workforce participation. These health-wealth cycles amplify health gaps between those who are able to work and those who are not in the older population, and underscore them with growing inequality in economic resources.

What we find

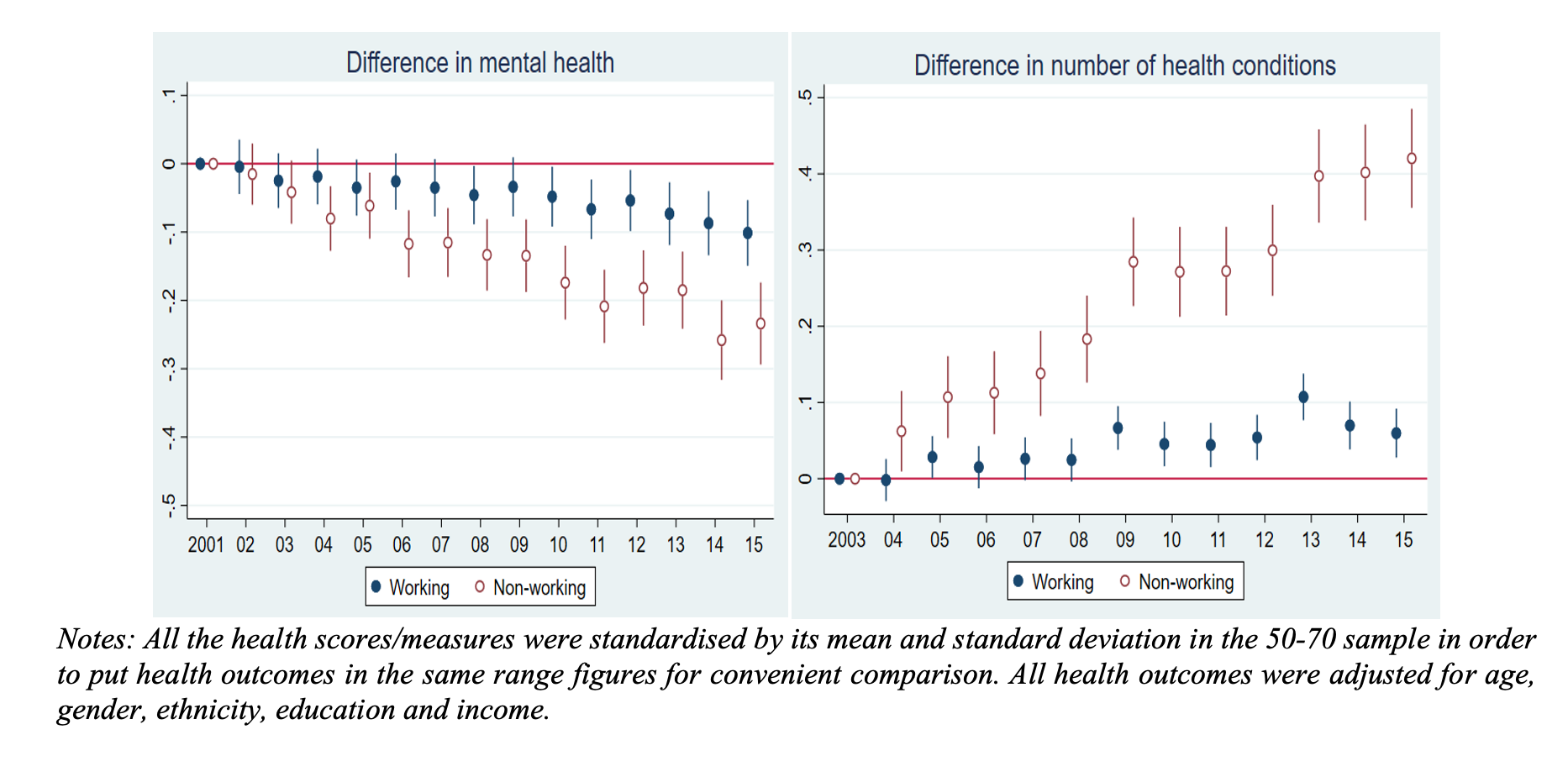

The HILDA data (2001-2015) shows that participation rates among older Australians increased by ten per cent during the period, a success for policy by any measure. However, the underlying health of older adults aged between 50 and 70 has slightly deteriorated after adjusting for the population composition. In addition, health gaps between those who were working into their older age and those who were not have widened over the 15-year period (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relative change of health outcomes from 2001 to 2015, Australians aged 50 to 70

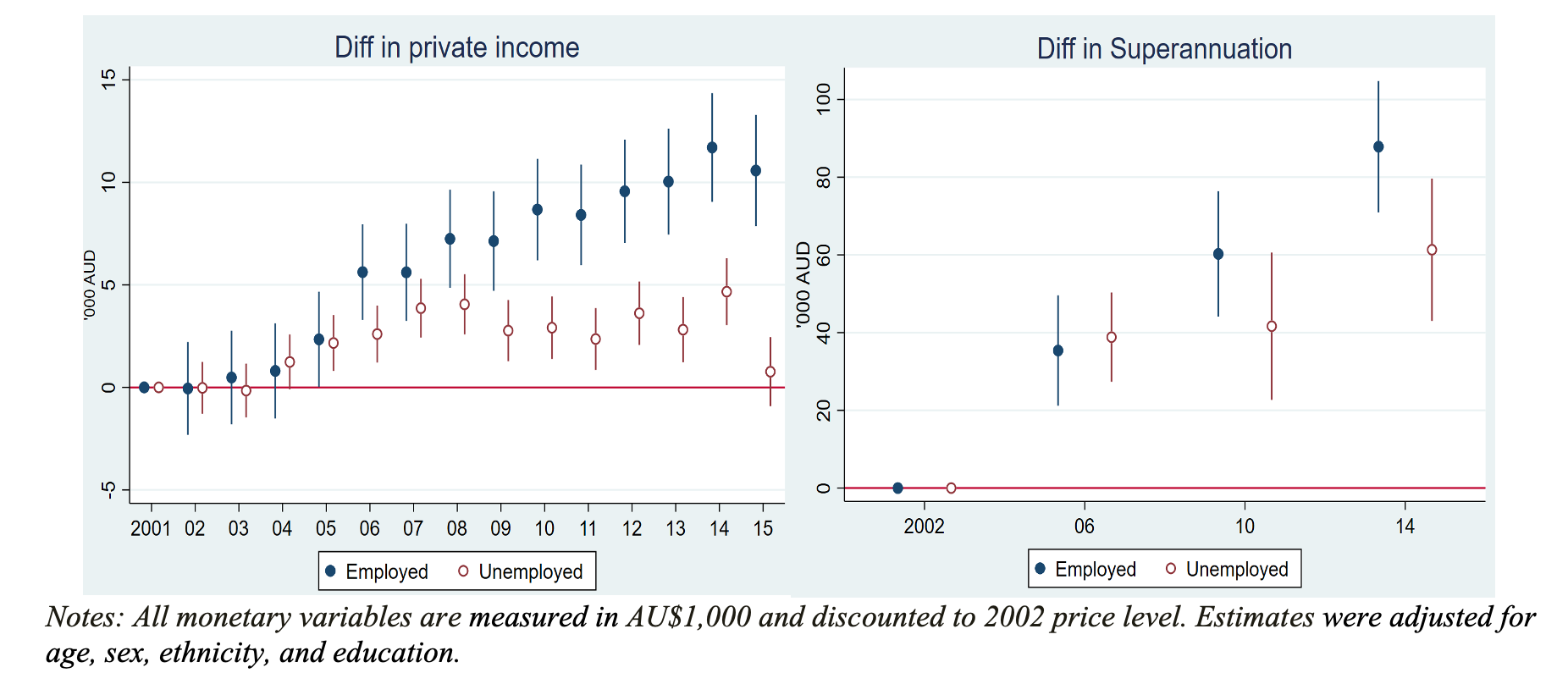

Overall, healthier older Australians remained in employment or returned to the labour market if they were previously non-employed, while those with poorer health remained non-employed or exited the labour market. We find that widening health gaps linked to workforce participation are accompanied by rising economic inequality in incomes, financial assets and superannuation (Figure 2). With the exception of a small group of healthy and very wealthy retirees, the majority of older Australians who were not working had low incomes, assets, superannuation and poor health. Better health enables people to remain or return to the labour market, while poor health keeps or pushes them out of the labour market.

Figure 2: Relative change of income and superannuation 2001-2015, Australians aged 50 to 70

Policy debate needed

Our evidence underscores the need for a new policy debate and action.

First, along with policies that support new skills and new jobs, we need protection and promotion of health, both in and out of the labour market, to be given a central platform in economic and workforce policies. There are diverse health needs and capabilities across all ages. These become more visible and impactful as people age and most of them are preventable.

Second, reducing health inequality between the employed and non-employed could be fundamental to reducing economic inequality, especially as Australians age and rely on savings and income supports. Investment in preventive health is not a feel-good add-on for Australia’s policy spend, but is one of the keys to promoting employment participation, reducing the need for financial support and mitigating public financial pressure.

Third, although some older non-employed adults were healthy and could choose not to work due to their wealth, the majority of non-employed older Australians generally had low incomes, low assets, little superannuation, and poor health. This group has both greatest need for financial support and security and least capacity to gain it from employment. In the short term, a significant group of older Australians will not be able to work simply because of their ill health. Alternative, and fair, options for income support need to be devised for this cohort. In the long term, there is an imperative to ensure the number of unhealthy and unwealthy older adults is minimised.

Currently, ageing and workforce participation policy in Australia does not address the health needs of older adults. The pension age eligibility of 67 in Australia is realistic for some, but our study shows it is unfeasible for many, especially for those who have poorer health. The widening, and connected, wealth and health gap we find among older Australians indicates a clear and urgent need to add policy actions on health, to policies that seek to increase workforce participation among older adults. While increasing longevity enables people to work longer in principle, policy success, and social equity, pivots on health status.

Acknowledgements: We thank Huong Dinh, Thuy Do, Amelia Yazidjoglou, and Cathy Banwell for their contributions to the published paper which provides inputs for the current post. We also thank Christine Labond for her thoughts and discussions on the Australian ageing workforce.

Recent Comments