Australia and South Korea share a surprising number of things in common, in spite of their differences, and this includes challenges and new approaches to tax and welfare systems. The size of Australia’s tax and social state are larger than that of South Korea but Korea is rapidly catching up. Both are facing difficulties in tax competition, the digital economy and how to reform tax and welfare systems to address demographic changes, gender inequality and changes in the nature of work.

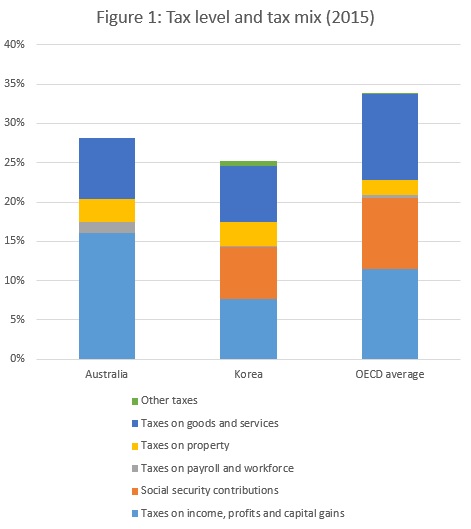

Both Australia (2016: 24.13 million population) and South Korea (2016: 51.25 million population) are at the lower end of OECD countries in term of tax level. South Korea recorded the fifth lowest tax-to-GDP level with 25.2% in 2015, while Australia was three places higher and recorded 28.2%. Both are well below the OECD average of 34%.

Both countries, however, have a different tax mix. Australia is more reliant on taxation on income, profits and capital gains, while South Korea has a relative diverse tax mix in which income and capital gain taxes, social security contributions, and value-added taxes contribute almost equal to the government coffers (see Figure 1).

(Source: Revenue Statistic 2017, OECD)

In term of public social spending, South Korea only spent 10.1% of its GDP in 2015, which is the lowest in OECD countries (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, Australia spent considerably more at 18.1% of GDP, although also below the OECD average of 21%.

Figure 2: Public social spending in OECD countries (2015)

(Source: OECD data)

In a recent workshop, New approaches to tax and welfare in Australia and Korea, researchers and government officials from Australia and South Korea met to discuss new research and policy approaches to common challenges of tax and welfare in both countries.

The workshop was funded by the Australia-Korea Foundation of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and organised by the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, ANU, partnering with the Korea Institute, ANU; the Department of Tax and Public Finance, University of Seoul; and the Korea Institute of Public Finance. It was held on 9 and 10 November 2017 at the Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU.

Among the common challenges identified in the workshop included ‘the race to the bottom’ tax competition leading to lowering corporate tax and tax incentives which affects both countries, and other countries in the Asia Pacific region and globally. International tax competition may be intensified by the US tax reforms led by President Donald Trump in which the US tax rate is expected to be as low as 20%. Other challenges were the role of the tax and transfer systems in addressing rising income inequality and sufficient funding for public goods, especially the role of income tax; and fiscal sustainability in the era of ageing populations.

The workshop started with a public panel discussion featuring Professor Peter Drysdale, Professor Peter Whiteford, Associate Professor Shiro Armstrong (all of three from Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU) and Dr An Jongseok from Korea Institute of Public Finance.

Professor Drysdale pointed out the share policy challenges and choices of the two countries, particularly having to deal with Trump’s America and it comes with geo-political and geo-economic uncertainties. He observed that “We have a common interests in making sure the system is strong. If not, our political, economic and security interests will be undermined,” he said.

Fiscal cost and progressivity of the tax-transfer system

The first session featuring a discussion on fiscal costs and progressivity of the tax and transfer system by Professor Whiteford, Dr An and Dr Chung Tran from Research school of Economics, ANU.

Professor Whiteford addressed the social transformation challenges for South Korea.

“Korea’s rapid economic growth has its consequences for social issues”, he said. These include Korea has the widest gender wage gap in OECD, high inequality between formal and informal workers, high relative poverty even among formal workers, and very wide differences between older people and people of working age.

He predicted social spending in Korea will be more than Australia in 2020 due to social aging.

Professor Whiteford also looked more generally at trends of income inequality in OECD countries and argued that the tax and transfer systems and government services can reduce inequality significantly.

He pointed out that South Korea is a puzzle and a ‘curious case’ because, despite its limited social spending and very little redistribution through taxes and transfers, its income inequality is below average. In comparison, Australia has a more targeted system to the poor than any other OECD country.

Dr An observed that in Korean society, preference for income redistribution is very strong and the new government led by President Moon Jae In has also showed support for this. Yet, this has not yet translated into support for a large progressive income tax and there are challenges in fiscal sustainability and tax, he warned. He looked at the long-term fiscal projection in Korea and said the total tax burden ratio would have to be increased to 39.4% in 2060 (compared to 24.5% in 2015) to keep fiscal sustainability in a context of growing welfare expenditure.

Dr An thus argued there is a need for government to reduce expenditure and, in case of any tax increase to pay for the welfare reforms, it should also be borne by most taxpayers and not just a small group of high income taxpayers or corporation. He said the government should focus on personal income tax, corporate tax and value-added tax.

Meanwhile, Dr Tran examined how progressive the Australian tax system is using the Suits Index, an approach similar to the Gini coefficient. Based his research on the series of sample data of individual tax return from the Australian Tax Office (ATO) from 2004 to 2014, he found the tax system in Australia has become more progressive recently as the Suits index in 2014 rose to 0.626 from a low of 0.611 in 2011, and bracket creep plays a role. But, a more challenging question, he said, would be what the optimal level of tax progressivity is.

Higher education financing and income contingent loans

The second session, focusing on higher education financing in South Korea, was presented by Dr Kim Byung Duck from Korea Institute of Finance, and Professor Bruce Chapman, the designer of the HECS-HELP system in Australia, with Dr Dung Doan from Research School of Economics, ANU.

In his presentation, Dr Kim introduced the student loan reforms in 2009 and 2010, which include both regular loan program and income contingent loan (ICL) programs. He found that, for ICL, although the borrowers are from low income families, there is substantial voluntary repayment beyond what is required. He speculated that, other than concerns of interest accumulation, this phenomenon might be due to the deeply-rooted Confucius tradition in South Korea which presumes education a family responsibility and ought to be supported by family.

For the regular loan program, Professor Chapman and Dr Doan also found that, despite the repayment burden borne by low-income graduates is heavy (this is also true after allowing a 10 year grace period of paying interests only), the delinquency rate in Korea is reportedly low. One possible reason is financial support from family to repay student loans. They therefore argue it is important to account for family support to debtors and intra-household reallocation of resources in future research. Research is continuing into the optimal design of the ICL scheme in South Korea.

Issues in international tax

The third session was on international tax issues. Associate Professor Byun Hyejung (Department of Science in Taxation, University of Seoul) and Professor John Taylor (School of Taxation and Business, UNSW) had a co-presentation arguing the case for revision of the 1982 Australia-Korea Tax Treaty, one of the oldest of Australian unchanged tax treaties. In particular, they identified some variations from the OECD Model convention in the 1982 Treaty, including Article 5 (which defines permanent establishment), Article 10 (on the treatment of dividend), Article 11 (on the treatment of interest) and Article 12 (on the treatment of royalty) and noted that these are the items where Australia might be likely to agree to changes.

Dr Jang Jaehyung from Yulchon law firm in Seoul discussed the controversial decision by the Korean Supreme Court in the Lone Star case, which has implications for the tax treatment of foreign private investment funds in Korea. He argued that in this case, the Korean Supreme Court was misguided in deciding that the beneficial owner or the substantial owner of the interest, dividend or capital gains of share is the investment fund rather than the underlying investors. Dr Jang further argued since the Corporate Income Tax Act has clarified its position in 2012 and 2014, this should prevail over the Supreme Court decision. The Korean Supreme Court’s decision is inconsistent with the OECD practice in this area and could lead to double taxation.

Issues in tax administration

The fourth session focused on tax administration issues. Professor Choi Wonseok, who has long experience working in taxpayer organisations and is based at the University of Seoul, presented a comparative analysis of Korean taxpayers’ organizations with their foreign counterparts, which have had a significant influence in both tax policy and administration reform, through applying political pressure to the Ministry of Finance and revenue agency. Professor Choi noted that there are still problems in these organizations despite their achievements. He listed five possible improvements include establishing an affiliated research institute to present a theoretical framework for the activities of taxpayers’ organizations and promoting wider participation of general taxpayers. The session turned light-hearted when participants were particularly curious about “the taxpayers’ song” proposed by the Korean Taxpayer Union in 2001.

Meanwhile, Associate Professor Celeste Black of University of Sydney critically assessed the external review mechanisms in place for taxpayers to hold the Tax Commissioner to account in Australia. She argued that despite the need for revenue authorities to possess strong power to able to administer the complex tax systems of today and to ensure that the legally correct amount of tax is paid, robust external accountability mechanisms are necessary. This will ensure that taxpayers’ rights are protected and they include both merits review system and judicial review system. Yet, informal mechanisms are at least as important to encourage early engagement and resolution of tax disputes. In Australia, accountability is quite well established but there are some gaps in accountability especially regarding investigations of fraud or evasion that date back many years.

Economic effects of the personal income tax

The fifth session featured Dr An Jongseok (Korea Institute of Public Finance), Professor Song Heonjae (University of Seoul) and Professor Robert Breunig (Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU) to discuss the economic effects of the personal income tax on distribution and work.

The personal income tax raises much less revenue in Korea compared to Australia, where it is by far the most important tax. Following recent policy debates in South Korea about increasing tax revenue, redistributing income more fairly and reducing the number of those who do not pay income tax, Dr An investigated the effective tax rates for all income levels. He argued that a change in top rate as planned by the government has limited effects on income redistribution and tax revenue and the government should instead consider a widespread tax rate increase to be applied to the middle income or higher groups.

Professor Song examined the effect of the change from an income tax deduction system to a tax credit system on labour supply in South Korea. He found that the change from a deduction to a credit produced a result that the tax burden of low-income workers had decreased, resulting in a higher after-tax wage rate, while the tax burden of high-income workers had increased, thus a lower after-tax wage rate. He also found that male workers, both low-income and high-income, had increased their working hours since the policy change. This suggests that, for low-income workers, the substitution effect is greater than income effect but this is opposite for high-income workers.

On the Australian personal income tax system, Professor Breunig presented a study co-authored with Shane Johnson which revealed taxpayer responsiveness to marginal tax rates through bunching evidence from the universe of taxpayer records between 2000 and 2014. Unlike studies from other countries, they found sharp bunching at all kink points in the Australian tax system, suggesting that the Australian taxpayers are responding to income tax thresholds where marginal tax rate changes. Elasticities are highest for high-income self-employed tax filers and also significantly higher for married women, women with children and younger tax filers.

Future of corporate tax

The final session was about the future of corporate and capital income tax. Dr Lee Sang-Yeob from Korea Institute of Public Finance looked at the introduction of tax incentives for dividend income from high dividend stocks in Korea and analysed the effects this tax incentive had on dividend payout. He found that companies with high levels of major shareholders’ ownership are more likely to respond to the tax incentives. However, overall, the tax incentives have had very little effect on the dividend payout of companies.

Professor Miranda Stewart presented a study conducted with David Ingles with modelling by Chris Murphy on alternative reforms of corporate taxation that could fund a corporate tax rate cut in Australia. The paper presented the case for replacing the dividend imputation system with a discount for dividends, broadening the corporate tax base by moving to comprehensive business income tax in which interest expense is not deductible for corporations, and introducing a financial rent tax. These reforms could fund a lower corporate tax rate in Australia and also enhance efficiency and reduce tax planning incentives.

The participants look forward to further research engagement and a second workshop to be hosted by the University of Seoul in 2018.

Presentations and audio of the public seminar are available here on the TTPI website, while the workshop presentations are here.

Further readings:

South Korea at the Strategic Heart of Australia’s Northeast Asian Economic Interests, by Peter Drysdale and Adam Triggs.

Pingback: Australia-Korea Tax and Welfare Workshop: South Korea at the Strategic Heart of Australia’s Northeast Asian Economic Interests - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

It was really a hepful and enjoyable two-day seminar !! ^^