The U.S. Social Security System is a defined benefit retirement system that uses a progressive formula to calculate own benefits based on past indexed covered earnings, the date benefits are claimed and a cost of living adjustment after retirement. Covered earnings have changed over time both with aggregate wages and with earnings history. There also are provisions for spouse and survivor benefits. Tax revenue is based on earnings up to a taxable maximum.

U.S. Social Security finances are out of balance. Future tax revenues will not be enough to cover promised benefits. To remedy this situation, some policy makers recommend increasing taxes. Others recommend reducing the growth of benefits, with some advocating means testing Social Security benefits.

Popular discussions conflate income and wealth as measures of means. For those policy makers who have thought about means testing Social Security, their proposals typically focus on incomes, but their rhetoric often suggests their concern is wealth. Many seniors with highest incomes do not have highest wealth, and similarly, those with highest wealth may not have highest incomes. Because income and wealth are not perfectly correlated, and neither is perfectly correlated with Social Security benefits, any means test will have different distributional effects depending on the criteria used to define high means. In addition, there will be substantial differences when a Social Security means test based on income is evaluated in terms of its effects on individuals arrayed by their wealth rather than their income. Similarly, a means test based on wealth will be evaluated quite differently by policy makers who believe that income is the appropriate basis for a means test than by those who believe that means tests should be based on wealth.

We examined the distribution of income and wealth for a sample of individuals from the Health and Retirement Study who were aged 69 to 79 in 2010. Income and wealth are far from perfectly related. We find they are correlated .50 among individuals, and .53 among households. Of our sample, 35.4 percent was in either the top quarter of the income distribution or the top quarter of the wealth distribution, but only 14.5 percent of the sample was in the top quarter of both distributions. Consequently, suppose that a means test was applied to those in the top wealth quartile. Now consider a policy maker who believed that income falling in the top quartile was a better basis for means testing. Such an individual would find that only 58 percent of those whose benefits were reduced fell in the top quarter of households ranked by highest income (14.5/25.0 = .58).

We tested a means test that would reduce Social Security benefits of affected individuals by $5,000, which is roughly equivalent to an existing Social Security Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP), where the individual also earns a pension from employment, mainly in the public sector.

In a second step, we smooth the relation between the means test and the individual’s income. Benefits are reduced proportionately to income (or wealth as appropriate). The proportionate benefit reduction is scaled so that it generates the same total benefit reduction for the system as is realized by reducing the benefits of those in the top quarter of income recipients or wealth holders by about $5,000.

The average Social Security benefit for an individual in the top quarter of the income distribution was $16,400 in 2010. An income based means test that reduced the average Social Security benefit for this group by about $5,000 would reduce benefits by about 30 percent on average. The average reduction for those in the top quartile of the wealth distribution would be similar if the means test applied to wealth. Among the 14.5 percent of the individuals who are in both the top income and the top wealth quartiles, the average benefit reduction would be $8,600 if the test were applied to wealth.

Income or wealth means tests and equity

We find that the distributional consequences of means tests change if the unit of measurement changes from an individual to a household and if married households and single households are considered separately. The distributional consequences also change if we include housing wealth; and if a means test’s measures of income and wealth are calculated before or after taxes. Means testing at program entry would reduce benefits more for younger retirees than older ones simply because younger people have not lived on their retirement resources for as many years.

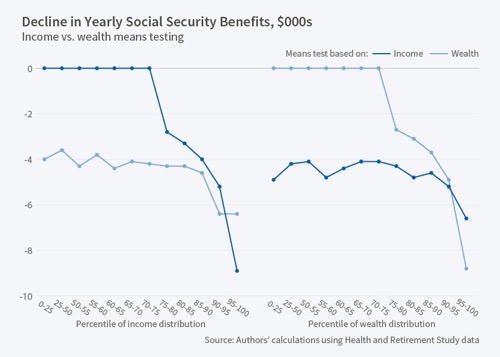

The means tests considered here would reduce the benefits of our sample by about nine percent, closing almost three fourths of the Social Security funding gap. Because different individuals are affected under alternative bases for a means test, we conclude that an income means test, compared to a wealth means test, could make a great deal of difference. This is shown in the Figure below.

Figure: Means Testing Social Security: Income Versus Wealth

This Figure shows policy makers the strengths and weaknesses of applying an income or wealth test and indicates that this choice for a means test clearly matters in terms of target efficiency and the policy maker’s view of equity. It also matters a great deal whether the effectiveness of the means test is judged by its impact on those with low or high income, or low or high wealth. A means test based on wealth may be more difficult to administer than a means test based on income. However, if wealth is the appropriate criterion for evaluating means, then means testing based on income is far from a perfect substitute for a means test based on wealth.

Means tests and the incentive to retire

Policy makers also need to remain aware of the effects of means testing on incentives to retire or on realizing wealth. Using current income as a basis for a means test would discourage the population from working longer. A means test based on income, that generates a $5,000 reduction in social security benefits, produces an implied marginal tax rate on current income of 7.5 percent (a $5,000 reduction on an average income of the top 25 percent of around $66,000). This figure is high enough to have nontrivial negative implications for the decision as to whether to defer income for retirement from a private retirement savings account such as an IRA or 401(k) account. If wealth is used as the basis for the means test, the means test is equivalent to a wealth tax of about 0.5 percent per year (a $5,000 reduction on an average wealth of the top 25 percent of around $926,000).

Our findings complement those in our earlier working paper that examined the consequences of using different measures of wealth, or measures of lifetime income as the basis for a means test. Once again we found substantial differences in whose benefits were redistributed under alternative versions of means tests, so that the redistribution fostered by a means test depends crucially on how one defines means.

We do not, in this paper, advocate means testing of Social Security benefits; nor do we take sides on the question of whether to base a means test on income or wealth. Instead, the aim is to clarify for policy makers the first order distributional consequences of means testing based on income or wealth, to give them a better understanding of the available policy choices and their effects.

This contribution is based on Alan L. Gustman, Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai, 2017. “Means Testing Social Security: Income versus Wealth.” National Tax Journal 70 (1), 111-132. Portions of this summary are taken from the published article with permission of the journal and also from a summary of the related working paper in the NBER Digest, September 2016. This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration through the Michigan Retirement Research Center with a subcontract to Dartmouth College and does not represent the opinions of either the Social Security Administration or of the MRRC.

Alan L. Gustman, Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai have authored a book and a series of articles using data from the Health and Retirement Study to examine the importance of pensions and Social Security in the wealth, savings and retirement behavior of those in the United States over the age of 50, to study Social Security policies, to document the extent of and effects of imperfect knowledge of pensions and Social Security, and to study the effects of the Great Recession on retirement and wealth. The book, published by Harvard University Press, is entitled Pensions in the Health and Retirement Study.

Recent Comments