Returning the Australian Government’s finances to a sustainable position following the Global Financial Crisis continues to present a challenge for government. While the 2017–18 Budget and subsequent mid-year update project a return to surplus and a decline in net debt, these projections are subject to risk and uncertainty.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) recently published a report titled 2017–18 Budget medium-term projections: Economic scenario analysis that attempts to quantify the impact on the medium-term budget projections of different economic growth and interest rate scenarios as the fiscal position is sensitive to changes in economic growth.

The Australian economy is currently growing below its estimated long-run capacity. The medium-term budget projections impose the technical assumption that the economy will grow to absorb any spare capacity over the five years following the forecast period and then grow at its long-run potential rate thereafter. The projections also assume that interest rates on government debt will rise to converge to long-term historical levels over the next two decades.

There is a fair amount of uncertainty in these assumptions. The recovery in the economy could be faster or slower than what is assumed in the budget. There is also uncertainty about the extent to which recent weakness in economic growth is due to temporary factors that are part of the economic cycle or longer-term structural factors. Furthermore, interest rates, internationally and domestically, remain persistently low and it is unclear when or whether rates will rise back to assumed long-run averages.

The potential rate of economic growth over the medium term in Australia is heavily dependent on labour productivity growth. Labour productivity refers to how much is produced for each hour worked. Other factors that can impact on the potential rate of economic growth, such as labour force participation, are unlikely to continue to contribute to growth. Labour force participation is at close to historical highs and is projected to fall reflecting the impact of the ageing of the population.

The budget assumes that labour productivity will grow at the 30-year historical average of 1.6 per cent every year. Productivity growth has fluctuated over the past decade which makes it difficult to discern the underlying trend. Labour productivity grew strongly over the period 2011–12 to 2013–14, averaging around 2.3 per cent per annum, but slowed to around 1 per cent per annum over the period 2014–15 to 2016–17. Slowing productivity growth is not a uniquely Australian phenomenon. Questions are being asked about why measured productivity growth appears to be so weak across advanced economies.

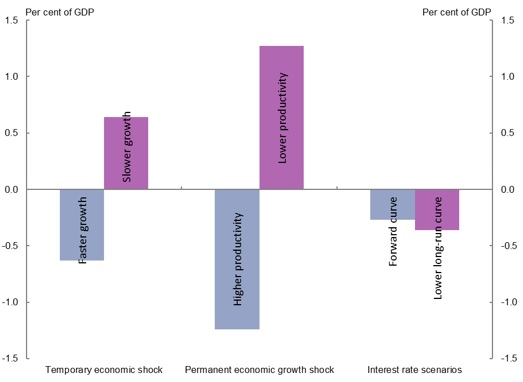

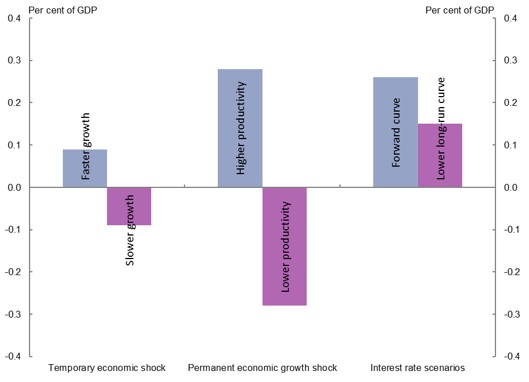

The PBO report quantifies the budget impacts of scenarios where there is a faster or slower recovery in economic growth (a temporary economic shock), permanently higher or lower annual labour productivity growth (a permanent economic shock) and lower long-run interest rates on government debt.

Running these scenarios through the PBO’s budget projection models produces different impacts on the budget position. We find that revenue moves broadly in line with changes in the nominal economy, while government payments are less sensitive to changes in the economy.

Temporarily stronger or weaker economic growth compared to the central projections has only a small impact on the government’s budget position over the medium term as demonstrated in Charts 1 and 2. This is because the impact of the shock on the level of real economic growth dissipates over time and the budget impact is limited to the effect of the shock on prices.

Chart 1: Projected difference from the central projection in net debt in 2027–28

Chart 2: Projected difference from the central projection in underlying cash balance in 2027–28

In contrast, permanent changes in economic growth due to changes in the rate of productivity growth have more significant impacts on the budget which will continue to increase over time.

The PBO projections cap revenue at 23.9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), consistent with the technical assumption used in the budget. Permanently stronger economic growth through higher labour productivity growth benefits the budget position to the extent that the additional revenue is not spent or given back as tax cuts (over and above the tax cap). Permanently weaker economic growth has a significant impact on the budget position as tax receipts weaken with slower economic growth, while government spending remains broadly unchanged initially before rising as debt servicing costs increase.

These results reinforce the importance to the budget of continuing efforts to enhance the long-run productive potential of the economy.

There is also uncertainty around the level of long-term interest rates, which underlie the medium-term budget projections. Interest rates, internationally and domestically, remain persistently low and it is unclear when (or whether) rates will rise back to long-run averages. The PBO report considers two scenarios for interest rates on government debt. In the first, interest rates are assumed to rise over time, but to lower long-run rates compared to those assumed in the budget (lower long-run curve). In the second, interest rates are assumed to be persistently low consistent with what is being observed in market transactions (forward curve).

Lower interest rates on Commonwealth issued debt, all other things being equal, reduce public debt interest costs and improve the underlying cash balance. However, depending on the level and duration of lower interest rates, these improvements would be modest because the stock of Australian Government net debt as a proportion of GDP is projected to be relatively low at around 8 per cent in 2027-28.

These scenarios highlight the need to consider the uncertainty around medium-term economic projections in managing the fiscal position. Taking into account uncertainty is particularly relevant in the current economic circumstances given the ongoing debate around whether the subdued economic outcomes of the past several years reflect a temporary or permanent phenomenon.

Recent Comments