There is understandable disappointment that the Government did not do more to improve the adequacy of JobSeeker, with many highlighting how this could have been done by scrapping the Stage 3 tax cuts. But the revenues from scrapping Stage 3 are not as great as most commentators suggest; and, though the Budget’s welfare measures provide some welcome relief, they leave fundamental problems in the structure of the welfare system and add to its complexity – one of the many issues that contributed to “Robodebt” and the difficulties welfare recipients have in dealing with Centrelink.

Stage 3 tax cuts

In earlier Austaxpolicy posts (2018 and 2019), I reviewed the three stages of the then Morrison Government’s personal income tax reform, suggesting that:

- Stages 1 and 2 broadly delivered tax indexation but could have done so more simply, without the messy LITO (low income tax offset) and LMITO (low and middle income tax offset), by directly increasing the tax-free threshold as the 2010 Henry Report proposed;

- Stage 3 be replaced by indexing the Stage 2 scale, preferably again simplifying the scale by increasing the threshold and abolishing LITO;

- Consideration could be given to a much simpler scale without Stage 3’s adverse distributional impact, even while including the scrapping of the 37% marginal rate step as the Morrison Government advocated, if the Henry Report approach was adopted with a much higher tax threshold and a standard tax rate closer to 35% applying from the threshold to around $200,000 when the 45% marginal rate begins.

This last suggestion is not fanciful. Not only would it be consistent with Henry, but it would be remarkably similar to the tax scale the Fraser Government introduced in 1978, and it would facilitate a much more coherent interaction between the tax and welfare systems.

Leaving aside such a more radical proposal, the cost and distributional impact of the Stage 3 personal income tax scale should not be based on the change at 1 July 2024 but on a comparison with the tax scale when Stage 1 was first implemented, indexed to 2024-25 to take into account bracket creep.

That is how Ben Phillips from the ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods has analysed Stage 3. His findings are that:

- The cost to revenue is around $6 billion a year, not $18 billion;

- The gains for those in the top quintile of incomes average around 1.4% of income;

- There are losses at the second and third quintile averaging around 0.6% of income; and

- There is no impact at the lowest quintile (as few of these have incomes above the tax-free threshold).

The cost to revenue would be lower in subsequent years if the scale were not indexed (probably disappearing within a year or two), as would the gains at high income levels, but the losses at middle and lower incomes would increase.

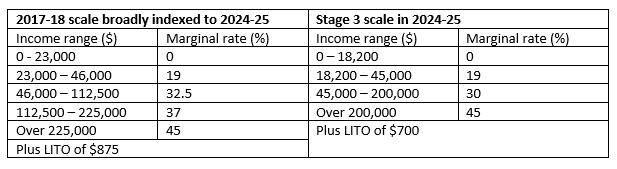

The following table compares the 2017-18 scale indexed to 2024-25 with the Stage 3 scale legislated to come into force that year. It happens that over this period the result is little different if using prices or wages (I have used 25% which broadly reflects wage movements), and I have done some rounding of the thresholds for illustrative purposes.

On this comparison, those on incomes between about $20,000 and $45,000 lose around $1,000 under Stage 3, with smaller losses up to around $90,000; those on $225,000 and above gain just under $5,000 (around 2% or lower), with slightly higher gains between $175,000 and $225,000 and lower gains between $90,000 and $175,000.

There is therefore a case for tweaking Stage 3 to reduce gains at the top and, more importantly, to stop the losses at the bottom; indeed, there is a case for a larger increase in the tax-free threshold coupled with abolition of LITO to simplify the system and facilitate greater cohesion with the transfer system. But there is not a large magic pudding of revenues available to direct elsewhere.

So the other message is that the Government must look elsewhere for additional revenues to fund improved welfare and public services.

JobSeeker and other welfare payments

While the budget measures – restoring the single parenting payment for sole parents whose youngest child is between 8 and 14, increasing JobSeeker for those aged 55-59 to the rate for those aged 60-67, increasing Jobseeker for everyone else more modestly and increasing Rent Assistance – will provide some relief to the most vulnerable, they further complicate the welfare system.

The Howard and Gillard Governments’ cuts to sole parents’ support would not have been so dire had JobSeeker been indexed to wages in line with the Howard Government’s 1997 decision about pension indexation. The sole parents concerned would still have had access to the same minimum income support if unemployed, but subject to firmer conditions about seeking paid employment.

The 1975 Henderson Poverty Inquiry recommended that the “Australian pension” (for those in longer-term needy circumstances) and the “Australian benefit’ (for those facing shorter-term contingencies) should have the same rates but different conditions. The Whitlam Government increased unemployment and sickness benefits to match the age and invalid pension rates. While Fraser allowed the single unemployment benefit to fall relative to the pension (and prices), other rates remained equal, and the Hawke Government re-established equal rates for all; conditions such as means tests continued to differ on the same logic as Henderson espoused.

With the different indexation arrangements introduced by Howard, and the Rudd Government’s decision to increase pensions further but not benefits, a large and growing gap emerged. The subsequent Henry and 2015 McClure reports tried to rationalise this by suggesting that ‘working age’ benefits be at a lower rate than pensions (including disability pensions for those of working age), but that the difference be fixed by having the same indexation arrangement.

With the widening gap, however, successive governments (and now the Albanese Government) have decided on incremental changes to focus on the most vulnerable of these vulnerable Australians. The result is highly questionable differences in support, perhaps reflecting prejudices of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ welfare recipients, and a system that is increasingly complicated.

Perhaps a valid case could be made for JobSeeker (and other ‘working age’ payments) to be lower than the pension as McClure and Henry suggest if those on Jobseeker are able to and regularly do supplement their benefit by casual or part-time work. But the evidence suggests that, even in times of low unemployment, few of our long-term unemployed have the necessary skills to be able to earn extra on any reliable basis. They need the carrots of training and education (perhaps with compulsory subsidised employment), not the stick of below poverty income support.

My preference remains to have common minimum income support across all pensions and benefits. Coupled with improved training and other support (the successful Jobs, Education and Training (JET) scheme for sole parents operating in the 1980s and 1990s is the best example), this would still strongly promote employment, including full-time ongoing employment.

But if that is a bridge too far, we need to have a clear target for the level of JobSeeker relative to the pension – the Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee’s proposed 90% or some other proportion above the post-budget ratio of 69% – which the Government commits to achieving when the budget permits.

In the meantime, to avoid the risk of once again widening the gap between JobSeeker and the pension, the Government could apply the pension indexation factor now. With high inflation and prices rising as fast as or faster than wages, there would be no cost in the coming year and negligible cost over the forward estimates.

Editorial note

The following paragraph was corrected on 29 January 2024: “On this comparison, those on incomes between about $20,000 and $45,000 lose around $1,000 under Stage 3….”. It was initially stated as “… around $1,000 compared to Stage 3”.

Other Budget Forum 2023 articles

The Costly and Unfair Stage 3 Tax Cuts Will Undermine the Progressive Income Tax and Worsen Inequality, by Kathryn James, Guyonne Kalb, Peter Mares, Miranda Stewart and Roger Wilkins.

Inflation Forecast, Fiscal Policy and Personal Income Tax Rates, by Chris Murphy.

Financial Support for Those on Low Incomes, by John Freebairn.

Will the Budget Reduce Inflation? By Michael Coelli.

Equity Is Hard to Achieve When Unfairness Is Baked into the System, by Robert Breunig.

A Small Investment in the Budget With a Big Policy Return? By Nicholas Biddle.

Labor Could and Should Have Gone Stronger on the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, by Rod Sims.

How Removing Parenting Payments When Children Turned 8 Harmed Rather Than Helped Single Mothers, by Kristen Sobeck.

Straightening Out the Super Tax Breaks Debate, by Brendan Coates and Joey Moloney.

The Priorities of Australians Ahead of Budget 2023-24, by Nicholas Biddle.

Dear Andrew

Worthwhile points but there are broader issues.

One of the basic problems of individual “progressive” income tax systems is the chronic failure to recognise non government income and asset transfers.

Many, if not most, people on government transfer payments have relatives who would be happy to support them if the income transfer were recognised in the tax system.

No one thinks back to when normal people detested the idea of being on public charity and thought it shameful.

But many, if not most, are now taxed into it.

On top of that, because we do not recognise the income transfers to, and expenditure on, children involved in labour reproducing itself, we have a fiscal-demographic decline.

Pingback: Albanese’s Proposal Doesn’t Fix Bracket Creep at the Bottom End, More Work Is Still Needed - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog