In addition to the small surplus forecast for the 2022-23 financial year, the coverage of the federal budget was dominated by the large expenditure items and changes. This is not surprising. The initial costs of the nuclear submarine program are eye-watering. And although many have argued that they do not go far enough, many of the other items announced on or just before budget night are costed in the multiple billions of dollars. This includes an increase in the JobSeeker Allowance payments (particularly for those 55 years and over), an increase in the bulk billing incentive as part of a suite of changes to Medicare, and direct payments to cover some of the increased size of energy bills.

There was one policy announcement though that received far less attention, but has the potential to dramatically change public policy in Australia. Buried on page 213 of Part 2 of the Budget was the following announcement:

$10.0 million over 4 years from 2023–24 (and $2.1 million per year ongoing) to establish a central evaluation function within Treasury to provide leadership and improve evaluation capability across Government, including support to agencies and leading a small number of flagship evaluations each year.

Like many of the other aspects of the budget, this was announced prior to budget night itself. However, it is only in the context of the full set of budget papers that we can start to see the long-term implications, for there are many other budget measures that touch on evaluations, both in terms of evaluations to come, and also policy initiatives that are ripe for being evaluated by a unit or with the support of a unit like the one being set up within Treasury.

Some context and the views of the public

Before thinking about evaluations and the budget, it is worth revisiting why such an investment is so important, and what the public’s reaction might be. The call for a greater evaluation capacity within government is not new, and is positioned by the current Government as part of the Australian Public Service (APS) Reform Agenda. The so-called Thodey Review had as recommendation numbers 26 and 27 to ‘Embed a culture of evaluation and learning from experience to underpin evidence-based policy and delivery’ and to ‘Embed high-quality research and analysis and a culture of innovation and experimentation to underpin evidence-based policy and delivery.’

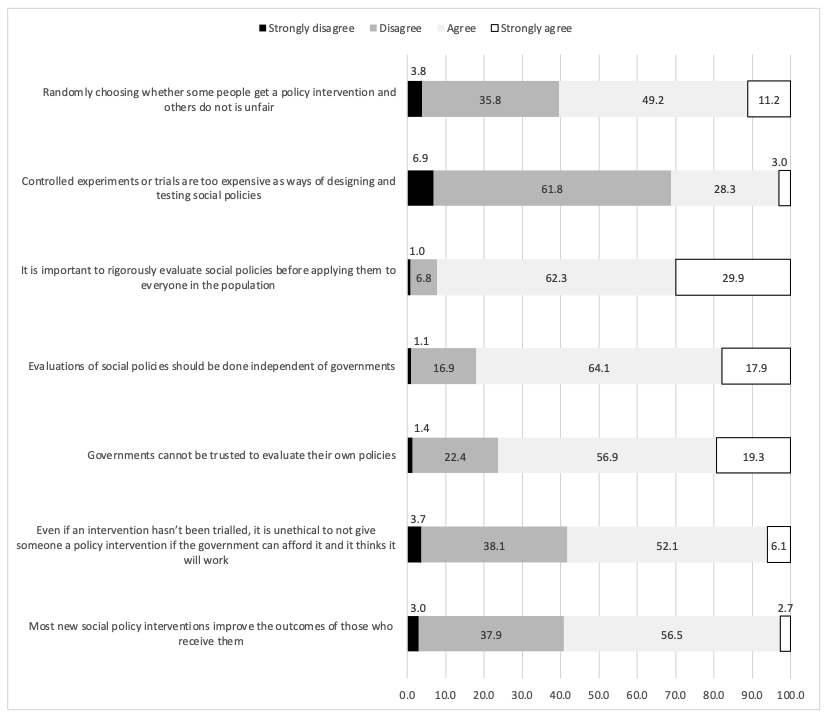

In some of the public-opinion research we have been doing at the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, our data collection also suggests that the general public is very supportive of additional trials and evaluations, but with some caveats. Specifically, as part of the 46th ANUpoll survey, data was collected from 3,468 Australians between the 10th and 24th of October, 2022. One of the questions we asked was for people’s agreement on a range of topics broadly related to trials and evaluations with the figure below giving the per cent of Australians based on whether they agree or disagree and whether they do so strongly.

Figure: General views of Australian adults on trials, evaluations, and social policy, October 2022

Source: ANUpoll, October 2022

Source: ANUpoll, October 2022

The statement with the strongest support is that ‘It is important to rigorously evaluate social policies before applying them to everyone in the population.’ Almost one third of Australians (29.9 per cent) strongly agree with this statement, with a further 62.3 per cent agreeing. Australians also think that evaluations or trials represent value for money, with more than two thirds of Australians (68.7 per cent) either disagreeing or strongly disagreeing that ‘Controlled experiments or trials are too expensive as ways of designing and testing social policies.’

The survey does pose some challenges for governments though when it comes to evaluations. From a methodological perspective, randomised controlled trials or RCTs often give the strongest evidence as to whether an intervention works or doesn’t work. However, around three in five of Australians (60.4 per cent) think that ‘Randomly choosing whether some people get a policy intervention and others do not is unfair.’ There are counter arguments against this view. For example, if we don’t know whether the intervention works, then being randomly allocated to a control group is just as likely to lead to improved outcomes as being allocated to the treatment group. However, if the Government and the new evaluation unit would like to incorporate more RCTs into the evaluations which it does undertake, then there may be some work needed to be done in convincing the general public of these counter arguments, and recognising situations where an RCT isn’t the best approach.

Perhaps more fundamentally, the Australian public has some scepticism towards governments undertaking evaluations of their own policies. Around three quarters of Australians (76.2 per cent) agree or strongly agree that ‘Governments cannot be trusted to evaluate their own policies’ with an even greater share of Australians (82.0 per cent) thinking that ‘Evaluations of social policies should be done independent of governments.’

These views don’t in any way negate the need for a greater evaluation capacity within government. Indeed, if there was a greater evaluation capacity, and the rigour and frequency of evaluations increased, then scepticism towards governments ‘marking their own homework’ might decline. Nonetheless, for large or more contentious policies, the evaluation unit and government more broadly would be wise to ensure independence of findings, both in reality and perception.

Some other budget announcements that could be evaluated

A key methodological consideration for a good evaluation is that the more effort and thought that is put in at the start of an evaluation, the greater the likelihood the evaluation findings will be robust. This makes it more likely that baseline data will be available if needed, but also that the program itself can be structured to have some regard for the evaluation component. So, while there are a lot of accumulated government programs that are in desperate need of high-quality evaluation, a useful place for the new evaluation unit to start might be with some of the programs also announced in the budget.

On the revenue side, for example, it was announced in the budget that ‘The Government will provide $89.6 million to the ATO and $1.2 million to Treasury to extend the Personal Income Tax Compliance Program’ and that ‘The Government will provide $588.8 million to the ATO over 4 years from 1 July 2023 to continue a range of activities that promote GST compliance.’ Similar interventions have been trialled in the past both in Australia and abroad, and if the evaluation unit were able to help improve what we learn from these programs, it could potentially pay for itself multiple times over.

There are also many payment measures announced in the budget that are crying out for a proper evaluation. Many of the initiatives in climate change could and should be evaluated, including household energy upgrades. In social policy though, there are a number of initiatives in very complex policy areas that should at least be evaluated robustly, and for many trialled before widespread roll-out. To name but a few, there is

- the Better, Safer Future for Central Australia Plan,

- paid practicums for educators in the ECEC sector,

- $32.8 million over two years from 2023–24 for the Clontarf Foundation,

- the National Teacher Workforce Action Plan,

- the trial of a new regional employment service approach,

- an improved delivery model for the Adult Migrant English Program,

- cultural competency within the APS,

- many of the initiatives related to the National Disability Insurance Scheme,

- financial wellbeing and capability supports for vulnerable individuals, families and communities in financial crisis and

- $199.8 million over 6 years from 2023–24 to address entrenched community disadvantage, including through place-based approaches, engaging with philanthropy and promoting social impact investment.

This is just a very short selection of a very long list of programs announced in this budget alone that could involve careful trials and evaluations. If these and other programs can be structured with the methodological challenges of good evaluations in mind (where possible with ethical randomisation), then the evaluation unit will indeed make a strong public policy contribution.

It is not possible to randomly allocate a nuclear submarine or the Brisbane Olympics. But there is much else that government does or wants to do that we don’t know whether works or not that could be structured in a way that we learn how to do better public policy in the future.

Other Budget Forum 2023 articles

The Costly and Unfair Stage 3 Tax Cuts Will Undermine the Progressive Income Tax and Worsen Inequality, by Kathryn James, Guyonne Kalb, Peter Mares, Miranda Stewart and Roger Wilkins.

Inflation Forecast, Fiscal Policy and Personal Income Tax Rates, by Chris Murphy.

Financial Support for Those on Low Incomes, by John Freebairn.

Will the Budget Reduce Inflation? By Michael Coelli.

Stage 3 Tax Cuts and JobSeeker – A Slightly Different View, by Andrew Podger.

Equity Is Hard to Achieve When Unfairness Is Baked into the System, by Robert Breunig.

Labor Could and Should Have Gone Stronger on the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, by Rod Sims.

How Removing Parenting Payments When Children Turned 8 Harmed Rather Than Helped Single Mothers, by Kristen Sobeck.

Straightening Out the Super Tax Breaks Debate, by Brendan Coates and Joey Moloney.

The Priorities of Australians Ahead of Budget 2023-24, by Nicholas Biddle.

Recent Comments