There is good news and bad news regarding income tax in the Federal Budget 2021. The good news is that Stage 3 tax cuts have not been brought forward. The bad news is that Stage 3 tax cuts are still on the books.

Stage 3 comes into effect in July 2024 and will deliver a big tax cut for the highest-income earners by introducing a single flat tax rate on every dollar earnt between $45,000 and $200,000, originally set at 32.5%, later reduced to 30%.

Tax cuts moving pieces

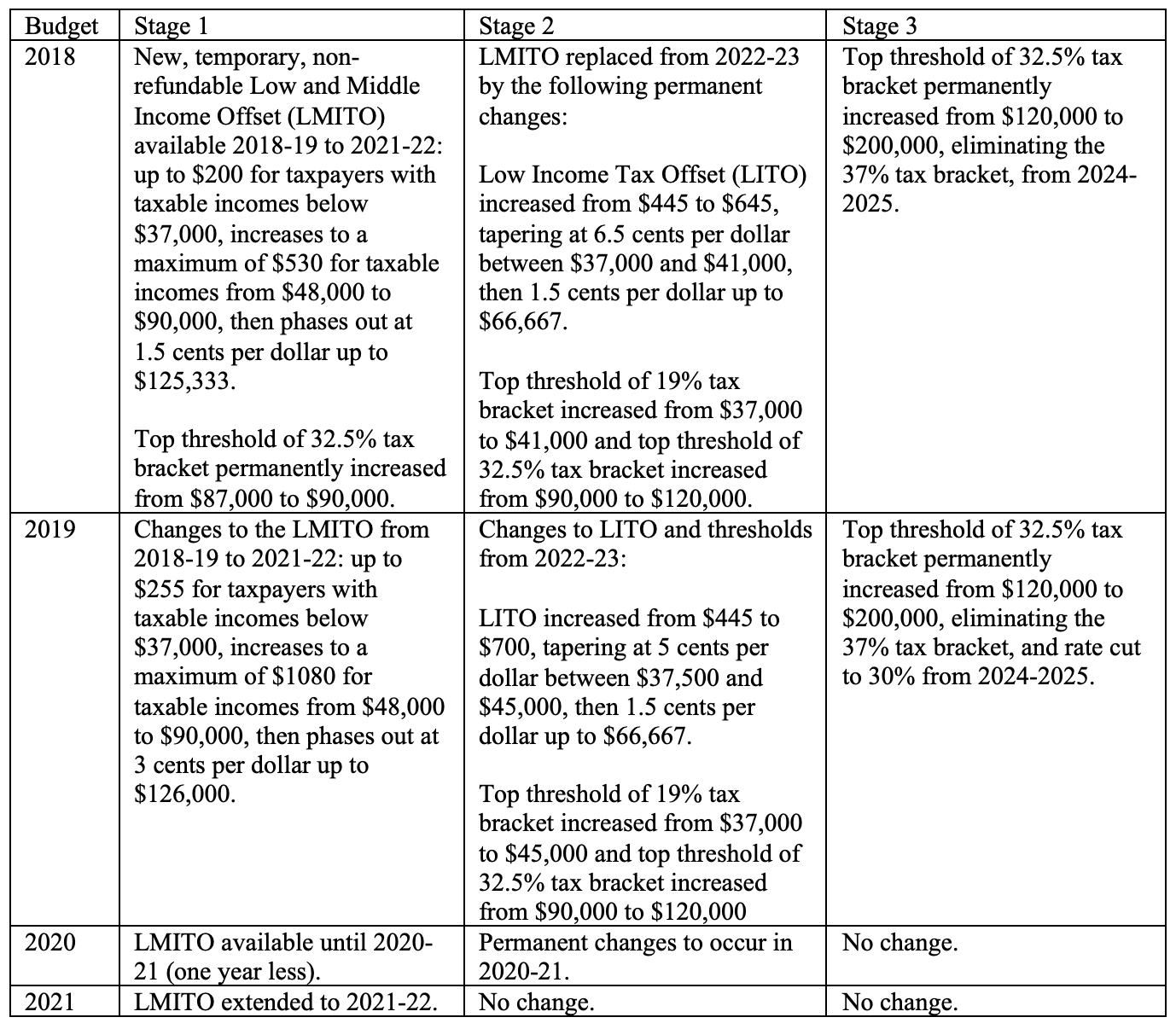

The Government has moved a few pieces since the original tax cut plan was laid out in 2018:

The main piece of Stage 1 was the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO, also colloquially known as the ‘Lamington’). The LMITO currently cuts taxes for taxpayers who earn less than $126,000 a year. The original plan was to remove the LMITO with the introduction of Stage 2. Stage 2 was indeed designed to provide a similar tax cut to anyone who had been receiving the LMITO, and a higher tax cut for higher-income earners.

In the 2020 COVID Budget, the Government brought forward Stage 2 but kept the LMITO, effectively delivering Stages 1 and 2 simultaneously. The Government intended to remove the LMITO this year but the Federal Budget 2021 extended it for an additional year at a cost of $7.8 billion. For as long as the LMITO remains in place, the tax cut for low- and middle-income earners is larger than originally intended.

The LMITO has issues…

Tax offsets of this kind make the tax system less transparent. The marginal tax rate schedule becomes messier when the withdrawal of the tax offset is taken into account. Individuals in the middle-income range between $90,000 and $126,000 face a 3% higher marginal tax rate than the one displayed in the marginal tax table.

The Henry Tax Review back in 2010 recommended eliminating most offsets and concessions. The LMITO was originally a temporary measure but, with Stage 2 brought forward, it becomes increasingly politically difficult to remove it. It would represent a tax hike for those individuals affected. The LMITO may be here to stay for a while with its cost and associated distortions in the middle.

… but its cost pales in comparison to the costs of Stage 3

When the Federal Government first unveiled the tax cut plan, the cost of Stage 3 was estimated at about $19 billion for the first year, increasing to about $29 billion a year by 2028-29. The current estimate sits around $17 billion when it takes effect in 2024-25. Wage growth has remained below forecasted every year since the tax cut plan was first unveiled.

Stage 3 mainly benefits high-income earners, who already benefit from threshold changes in previous stages. Grattan Institute modelling suggests that around 60% of the total benefits from the tax cut plan will flow to the top 20% of income earners.

The Government has argued that the tax cut package, particularly the large tax cuts at the top, will boost growth from improved incentives to work. Recent evidence suggests that past reductions in top marginal individual income tax rates have had an insignificant impact on growth and employment but may have contributed to higher income inequality.

Tax cuts are not tax reform…

Early research on the impact of tax rate changes focused on labour supply, typically measured by hours worked. Labour supply elasticity estimates tend to be relatively small and, in particular, there is no evidence that high-income taxpayers have substantially large labour supply elasticities.

Modern research focuses on the elasticity of taxable income, which captures all possible behavioural responses through which income can respond to rate changes, including income shifting, tax avoidance and tax evasion. Recent research has shown that a decrease in the taxable income of top income earners in response to a higher tax rate often reflects an increase in tax avoidance, not a change in hours worked. This suggests that an alternative, and possibly more effective, avenue to raise revenue from top earners is to close tax loopholes.

Genuine tax reform should go beyond tax cuts. It should encompass both the marginal tax rate schedule and the definition of income. It should properly account for the ways in which the tax and the transfer systems interact. In Australia, secondary earners currently face the largest effective marginal tax rates.

… and prevent genuine expenditure reform

The Government included a series of expenditure items in the Federal Budget 2021: notably, $17.7 billion over 5 years for aged care, $2 billion for mental health and $1.7 billion over 3 years for childcare subsidies. The extra spending has been welcomed but, in all cases, falls short of what experts considered necessary. The Royal Commission into aged care recommendations would require about $10 billion a year, the Productivity Commission report into mental health identified reforms worth $2.4 billion and the Grattan Institute report on childcare suggests boosting spending on childcare subsidies by $5 billion a year.

The huge cost of the looming tax cuts prevents larger investments in all these areas, which the evidence suggests would boost growth and improve wellbeing. No such evidence exists for the presumed impacts of tax cuts for high-income individuals.

Other Budget Forum 2021 articles

Structural Changes, but No Sustainability Reset, by Miranda Stewart.

This Was an Election Budget on Steroids, by John Hewson.

The Volunteer Workforce Is Key to Achieving Budget Priorities, by Sue Regan.

Australia’s Planned Patent Box: A Means of Stimulating Innovation? By Sonali Walpola and Tracy Wang.

Could It Pack a Punch? Maybe, but There’s a Lot at Stake: The Reactivation of the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle, by Alex Evans.

Don’t Shoot in the Dark: Business Support in the Australian Budget, by Andrés Bellofatto, Begoña Dominguez and Jorge Miranda-Pinto.

Excellent note by Dr Racionero. The ‘budget for women’ is not for women…(considering the planned taxation for low income earners and the very poor childcare investment)!

So increasing expenditure is expenditure reform but cutting tax is not tax reform.

An interesting inconsistency.