In 2018, the Government introduced a new Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO), which applies in addition to the Low Income Tax Offset (LITO). We examine the effect on equity between resident individual taxpayers of the LMITO and LITO, together with 2019-20 Budget proposed changes. We compare these measures with the Opposition Australian Labor Party (ALP) election proposal.

All taxpayers eligible for LMITO are better off compared to their 2017-18 position. However, we argue that recent initiatives operate inequitably. Under both Government and ALP policies, middle income earners fare better than low income earners when the combined offset entitlement is considered.

Lead up to 2019 LMITO proposals

The LMITO, which applies for four years from 2018-19, are part of ‘Stage 1’ of the Government’s ambitious three stage Personal Income Tax Plan, which was enacted into law in June 2018. A further measure starting in 2018-19 is an increase to the upper threshold of the 32.5% bracket from $87,000 to $90,000.

Stage 1 is also essentially endorsed by the ALP. Stage 2 involves further tax cuts that mainly benefit upper-middle and high income earners, while Stage 3 benefits only high income earners, as pointed out in the media, and 2018 Austaxpolicy analysis. The ALP has promised to repeal the Government’s Stage 2 and Stage 3 measures if it wins office.

In Budget 2019-20, the Government proposed an approximate doubling of LMITO. In its Budget Reply, the ALP matched the Government’s LMITO plan, and also announced a greater offset (compared with the Government) for those earning no more than $37,000.

LITO and LMITO and their interaction

The LITO was introduced in 1993-94 to provide tax relief for low-income earners in a form that would not also reduce the tax payable by high income earners. The LITO was previously quite high, being $1,500 in 2011-12. In 2012-13, the then-Labor Government reduced the LITO to $445 in conjunction with raising the tax-free threshold to $18,200.

The LITO is available to resident taxpayers earning no more than $37,000, with a partial (tapering) offset for taxable incomes between $37,000 and less than $66,667.

Under the Government’s previously enacted plan, from 2018-19 to 2021-22, taxpayers earning no more than $37,000 would also be entitled to $200 LMITO, with a full LMITO of $530 being available between $48,000 and $90,000 and a partial (tapering) LMITO between $90,000 and $125,333.

In Budget 2019-20, the Government proposed to increase LMITO to $255 for taxable incomes of $37,000 and less, and to increase the full LMITO to $1080 for incomes between $48,000 and $90,000. This tapers off between $90,000 and $126,000 (the slightly higher threshold is needed for the new offset to taper uniformly).

The LITO and LMITO are non-refundable offsets: only taxpayers earning above the tax-free threshold can benefit. For example, in 2017-18, the full benefit from LITO is realised at $20,542 where the pre-offset tax liability ($445) is matched by the LITO and reduced to nil, and a benefit from the LMITO is only obtained when the LITO-inclusive tax free threshold is exceeded (above $20,542).

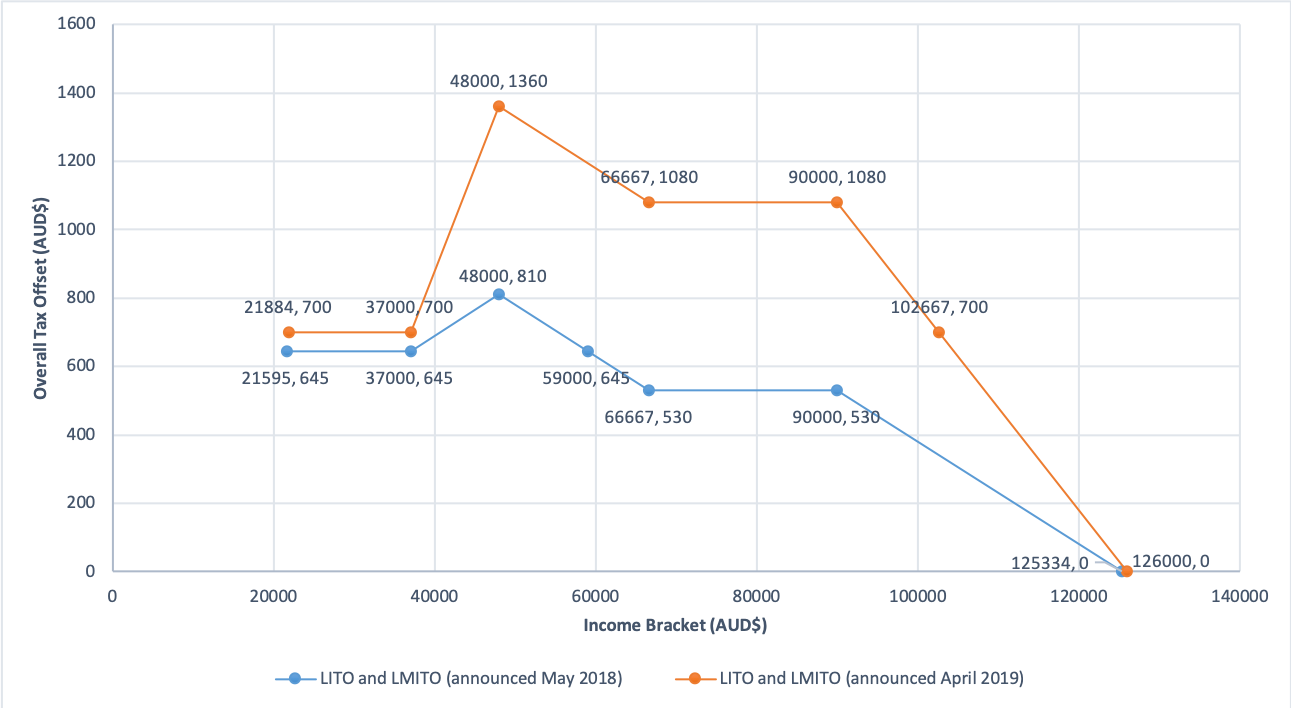

The eligibility for LITO and LMITO partially overlap. Taxpayers earning below $66,667 are entitled to all or some of LITO and LMITO. The combined offset entitlement is represented in Figure 1, which separately shows the combined offset under the 2018 legislation and the Government’s 2019 proposal. As shown, taxpayers earning no more than $37,000 are entitled to a combined offset of $645 under the 2018 measures ($445 LITO and $200 LMITO) or $700 under the 2019 plan ($445 LITO plus $255 LMITO). Taxpayers earning $48,000 are in the optimum position, receiving the full LMITO ($530 under 2018 legislation or $1080 as per Budget 2019) and a partial LITO ($280), giving a combined offset of $810 under 2018 legislation or $1360 under the 2019 plan.

Figure 1: LITO and LMITO under the Government’s 2018 measures and 2019 plan

There does not appear to be a sensible rationale for this preferential treatment of middle income earners over low income earners. As seen in the graph, under the 2018 measures, taxpayers earning between $37,000 and $59,000 obtain a higher combined offset compared to taxpayers with taxable income of less than $37,000. The proposed measures in Budget 2019-20 exacerbate the disparity: while each group is better off, relative equities are undermined further; taxpayers earning between $37,000 and up to $102,667 obtain a higher combined offset (variously, a combination of LITO and LMITO or all or part of LMITO) than taxpayers earning less than $37,000.

A further glaring source of inequity is illustrated in the far steeper slope of the increasing offset between $37,000 and $48,000 under the 2019 plan compared to 2018. This arises due to the proposed increase in LMITO (LITO is constant throughout the relevant period). Pursuant to the 2018 legislation, between $37,000 and $48,000, the LMITO increases by 3 cents for each dollar of taxable income over $37,000. Under the 2019 plan, between these thresholds, the LMITO increases by 7.5 cents for each dollar above $37,000. The Government has chosen not to publicise this (extraordinary) incremental increase to the LMITO between $37,000 and $48,000. By comparison, with the 2018 measures, the Government openly acknowledged a 3 cents per dollar increase to the offset between these thresholds.

Labor’s Plan

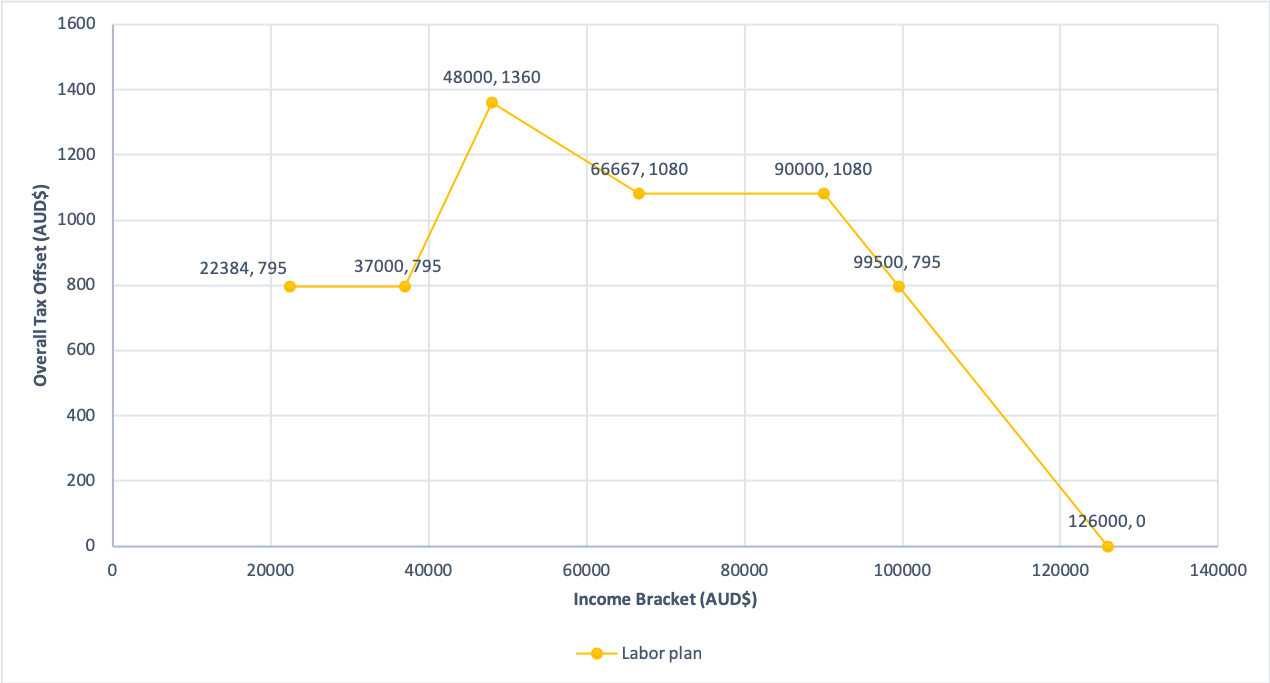

In its Budget Reply, the ALP largely matched the Government’s 2019 LMITO proposal (see the ABC’s outline and comparison of Labor’s policy). The only difference is that it would offer a greater offset of $350 for taxable incomes of $37,000 or less (compared to $255 under the Government’s plan). This greater offset would increase the effective tax free threshold to $22,384, which is $500 more than under the Government’s 2019 proposal, and nearly $800 greater than under 2018 enacted measures. However, as shown in Figure 2, the ALP plan similarly undermines relative equities compared to 2018 measures. It is only slightly less inequitable: taxpayers earning between $37,000 and $99,500 (compared to $102,667 under the Government’s plan) obtain a greater combined offset than those earning $37,000 or less.

Figure 2: LITO and LMITO under Labor’s plan

Maintaining a progressive tax system?

In a glossy publication entitled ‘Lower Taxes’, released on Budget evening 2019, the Government claims its tax measures for individuals will ‘maintain a progressive tax system’ (at p.9). Most obviously, the Government’s Stage 3 measures—which effect a substantial ‘flattening’ of individual income tax rates —are inconsistent with such a claim.

In substantiating its claim that a progressive tax system is maintained, the Government points out that high-income taxpayers will still contribute the largest share to tax revenue under its plan (e.g., ‘60% of all personal income tax will be paid by the highest earning 20% of taxpayers’: p. 9). But this is not how progressiveness is evaluated. In the context of tax policy, a progressive system means one where the average rate of tax paid increases with taxable income, in contrast to a system with a flat rate of tax (e.g., see Peter Varela’s TTPI paper). Even if a purely flat (or proportional) tax rate were to apply, it would be true that the highest income earners would pay the bulk of tax. This is a function of the fact that they have more taxable income.

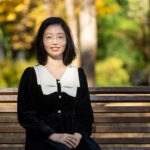

To assess whether the enacted and proposed offset measures affect progressivity, we compare the effect on average tax rates, using 2017-18 as the reference year. The Table below shows the tax liability (columns 2, 4, 6, and 8) and average tax rate (columns 3, 5, 7 and 9) for various income levels (column 1), which represent points of interest under LITO and LMITO. The tax paid is calculated at resident rates (inclusive of Medicare Levy), and takes account of LITO and LMITO where applicable. Average tax rate expresses tax liability as a percentage of taxable income. Column 3 shows average tax rates in 2017-18 (where only LITO applied) and columns 5, 7 and 9 show average tax rates under the 2018 measures, the Government’s 2019 plan, and Labor’s plan, respectively.

With the 2018 measures (column 5), and the 2019 Government and Labor proposals (columns 7 and 9), the scheme is still progressive in the sense that average tax rates increase with taxable income.

To cleanly examine the impact of the LMITO, we can focus on taxable incomes between $48,000 and up to $87,000 (which were unaffected by the increase to the upper threshold of the 32.5% bracket). Within the range of taxable incomes fully eligible for LMITO (e.g., when $87,000 is compared to $48,000), there is an increase in progressivity. This is because the offset (e.g., $1080 under the 2019 plan) necessarily represents a larger fraction of lower taxable incomes. For example, in 2017-18, the average tax rate on taxable incomes of $87,000 was 24.78% and 16.31% for taxable incomes of $48,000, being a difference of 8.47%. Under the 2019 LMITO proposals of the Government and Labor (identical in this respect), the difference in average tax rates would increase to 9.48%.

Overall tax progressivity is declining

However, overall, tax progressivity is reduced by these changes. In 2017-18 (pre-LMITO), the average tax rate on $66,667 was 21.82% whereas the average tax rate on $37,000 was 10.45%, being a difference of 11.37%. Under the 2018 enacted measures, this difference in average tax rate for incomes between $66,667 and $37,000 contracts to 11.1%, and the 2019 Government plan substantially narrows the difference to 10.44%. Labor’s 2019 plan also reduces progressivity, but not to the same extent; compared to 2017-18, the difference in average tax rates between incomes of $66,667 and $37,000 narrows from 11.37% to 10.70%.

While the progressive nature of the tax system for individuals is not yet dismantled, it is concluded that recent initiatives undermine relative equity between low and middle income earners. This is particularly true of the 2019 proposals of both parties which undermine relative equity even further compared to 2018 measures.

Other articles in the Budget Forum 2019

The Instant Asset Write-off Will Lift Investment—but Is That What We Want?, by Steven Hamilton

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 1, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Refundable Franking Credits: Why Reform Is Needed (and Why It Should Be Targeted) – Part 2, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

“All Without Increasing Taxes”? A Closer Look at Treasurer Frydenberg’s Refrain Repeated Eight Times in His Budget Speech, by John Taylor and Ann Kayis-Kumar

Forecasts and Deviations – the Challenge of Accountable Budget Forecasting, by Teck Chi Wong

Targeted Tax Relief Makes the Tax System Fairer but the Economy Poorer, by Steven Hamilton

A Simpler Tax System Should Spark Joy—Eliminating Tax Brackets Sadly Doesn’t, by Steven Hamilton

A Budget That Supports Indigenous Australians?, by Nicholas Biddle

Women in Economics 2019 Federal Budget Reflections, by Danielle Wood

Tax Progressivity in Australia: Things Aren’t as Simple as They Seem, by Chung Tran and Nabeeh Zakariyya

Coalition and Labor Voters Share Policy Priorities When They Are Informed About Inequality, by Chris Hoy

Future Budgets Are Going to Have to Spend More on Welfare, Which Is Fine. It’s Spending on Us, by Peter Whiteford

Recent Comments