Promising a balanced budget in the near future is starting to become a tradition in Australian politics. (I have written a similar article about this issue last year.) This year’s budget finally confirmed that there is a revenue problem and the government has vowed to address the problem by increasing government revenue substantially to move the budget back to surplus within four years.

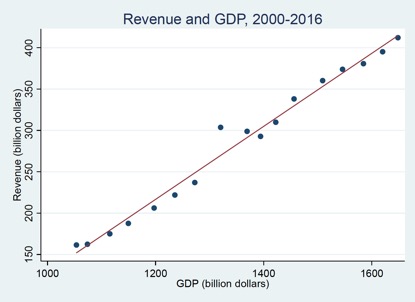

In this article, I present a few simple statistics that illustrate why the government will probably fail to return to a surplus within a few years. To understand why the predictions of the government are implausible, it is useful to look at the link between government revenue and the size of the economy. The figure below shows the relationship between government revenue and GDP since 2000.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

The relationship is linear, which means that GDP forecasts for the coming years can be used to predict future government revenues. These predictions will be fairly accurate as long as the GDP forecasts are correct. Unfortunately, the assumptions about GDP growth in the Budget 2017-18 are quite optimistic (2.75% in 2017-18 and 3% afterwards). Budget calculations should be based on conservative growth assumptions to account for some of the fiscal uncertainty associated with predicting future outcomes.[1] It is useful to consider alternative growth scenarios to understand the implications of economic growth assumptions for government revenue.

The figure below shows actual government revenues for the period 2000-01 to 2016-17 and the predicted revenues for the period 2017-18 to 2020-21 based on alternative growth scenarios. The first scenario uses the growth assumptions of the Budget 2017-18. Based on these assumptions, my prediction (the red line) is much lower than the prediction of the Budget 2017-18 (the blue line).

The difference between my prediction and the Budget 2017-18 figures reveals that the government has not only made optimistic assumptions about future economic growth but also about how economic growth will be translated into higher revenues. Given the relationship between GDP and government revenues that we have seen in the past, it seems highly unlikely that the revenue predictions in the Budget 2017-18 are correct.

In contrast, the red line looks like the continuation of a trend that can be expected if the economy continues to grow as much as it has done in the past. Unfortunately, this trend is much lower than the predictions made in the Budget 2017-18: The difference between the blue line and the red line implies that the government revenue in 2020-21 will be $36 billion lower than assumed in the Budget 2017-18, even if the optimistic growth assumptions are correct. I also present the predicted revenues resulting from alternative scenarios, which assume a constant growth rate over the period 2017-18 to 2020-21. The predicted revenues of Scenarios 2-4 are much lower than those of Scenario 1.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

The revenue predictions may be used to study the impact of different growth scenarios on the fiscal balance. The figure below shows the fiscal balance predicted in the Budget 2017-18 (the blue bars) and the predictions based on the actual relationship between GDP and government revenues over the last 16 years. Under the growth assumptions made in the Budget 2017-18 (the red bars), the fiscal deficit would increase to about $34.5 billion in 2018-19 and then decline to about $25.1 billion in 2020-21. This deficit is nowhere near the surplus of $11.4 billion predicted in the Budget 2017-18.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues and fiscal balance numbers presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

Note: Own calculations based on information about actually collected revenues from Final Budget Outcomes 2000-01 to 2014-15 and revenues and fiscal balance numbers presented in the Budget 2017-18; real GDP data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

Assuming a growth rate of 2.5% over the next four years (which is still quite optimistic) increases the fiscal deficit to about $38.9 billion in 2020-21 (Scenario 2, the green bars). Assuming 2% growth is associated with a deficit of about $54.4 billion in 2020-21 (Scenario 3, orange), and a growth rate of 1.5% increases the deficit to $69.8 billion in 2020-21 (Scenario 4, grey). Taken together, these results indicate that the fiscal deficit is likely to remain substantial in the absence of a serious tax reform.

The analysis performed in this article is based on a data set that can be downloaded here. The Stata code that was used to generate the results is available here as a text file.

[1] Conservative growth assumptions are also appropriate because a considerable part – about 0.5 percentage points – of GDP growth in 2017 and 2018 may be attributed to the ramp-up in liquefied natural gas (LNG) production. LNG is not expected to generate significant employment growth because LNG production is very capital intensive. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) argues that “a sizeable portion of LNG profits will flow to foreign investors and tax revenue will be constrained by deductions (such as depreciation).” I thank Christian Gillitzer for pointing this out to me.

Recent Comments