A greater diversity of resources is needed in the energy mix. Biofuels are currently a minor component in the energy mix and this shortfall should be tackled. One outcome of the COVID-19 crisis has been the reduction in fossil fuel usage — and the subsequent fall in greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. It has provided some hope amidst general despair. Tax law and government policy to promote biofuels is part of a just transition to a low carbon economy.

Ethanol is a typical biofuel mainly used as an energy fuel for transport. This biofuel has recently come to the fore of our attention in the context of COVID-19, as ethanol (also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol), is a key ingredient in hand sanitiser. Ethanol is the inebriating ingredient of many alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, and spirits such as gin, but stocks have been diverted use in public health. Feedstocks for ethanol include food crops and crop waste, for example, grains and sugar cane, that are processed into bio-ethanol via a variety of methods, such as fermentation. There are now many innovations beyond these ‘generation one’ feedstocks.

In our co-authored biofuels article funded by the Monash Energy Institute, we examine how tax law and policy can encourage investment in innovative research into lowering the cost of biofuels for transport, as part of a just transition to a low carbon economy. The aim was to re-think the fiscal lever of tax. We asked whether there was a contemporary tax policy narrative to elicit from earlier 2000s Australian studies on biofuel innovation. The primary research question asked whether the earlier 2000s Australian studies on biofuel innovation might help inform contemporary tax law and policy relevant to the transport biofuels. The second research question concerned the type of fiscal support might encourage more consistent biofuels innovation today.

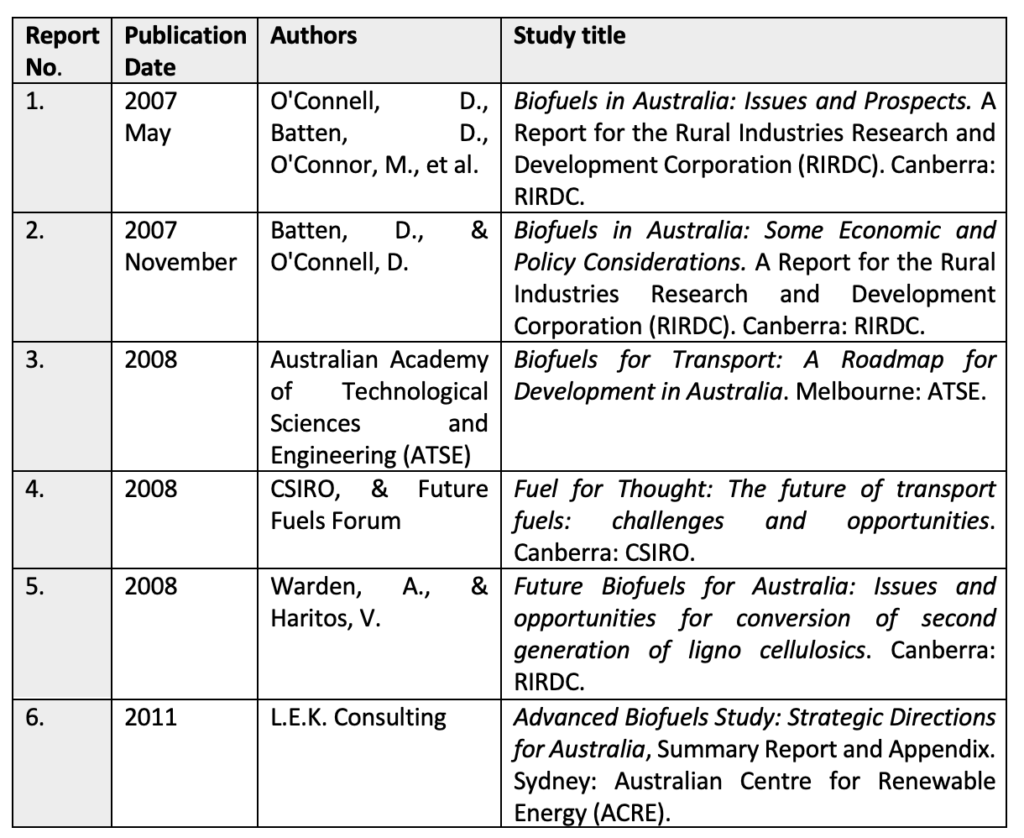

Our research drew on biofuel studies from the ‘golden era’ of Australian biofuels investigations over the period from 2007 to around 2011, with the goal of widening the benefits of these studies beyond the technical and economic attributes of biofuels alone. The researchers interrogated these findings through the lens of the ‘energy justice’ framework.

Energy Justice

Energy justice is a qualitative tool that provides decision-support for energy regulation by ‘policy makers to balance the energy trilemma of competing aims’ from economics (such as energy pricing), politics (such as energy security) and the environment (sustainability, specifically here, of biofuels). Energy justice can be considered through the following principles:

- Availability underpins the community’s right to efficient, high-calorific energy.

- Affordability is related to access to energy for basic heating, cooking and transport needs.

- Due process is about respecting human rights in the production and use of energy.

- Transparency and accountability about energy is a community right.

- Sustainability is a key objective of natural resource extractive activities.

- Responsibility is about the requirement to protect the natural environment.

Early 2000s Australian studies on biofuel innovation

The selected reports from the early 2000s (see Table 1) on biofuels research dealt with the economics of biofuels, and had a focus on transport, which today accounts for 19% of national emissions. Technical, scientific and economic modelling approaches were used in those reports. In terms of the environment, some reports stressed the contribution of biofuels to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. As for politics and policy, the reports generally called for government policy to support technological innovation to realise future, low-cost production of biofuels. Energy security was raised as a common issue.

Table 1. Findings: selected major Australian biofuel studies, 2007-2011

In summary, with regards to implications for contemporary tax policy, the reports had expected that a carbon trading system would be introduced and would remain. As a result, biofuels research of the early 2000s were not particularly focussed on greenhouse gas emissions: it was an issue to be addressed by government policy and legislation. The selected reports revealed that in the period around 2007 stability in government policy was the norm so there was little or no discussion on energy policy, it was more about financial support from the state. In 2007 Australia had voted in a Labor government (under Kevin Rudd) after 11 years of conservative coalition leadership. The electorate was yet to endure the policy instability that came with government leadership changes from the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd era of 2010-2013 and the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison era from 2013 onwards.

Current fiscal support to encourage biofuels innovation

The research next explored current government fiscal support, such as the federal taxation system or federal and state direct grants and loans, which might encourage biofuels research, innovation and investment around Australia.

Federal support

We found that recent federal tax changes have likely had a negative effect on biofuel innovation investment. These changes included the 2014 repeal of the carbon tax; the long delay from the 2016 research and development tax incentive (RDTI) tax concession inquiry to the 2019 Bill; and the 2015 introduction of fuel excise on biofuels along with the removal of the alternative fuel offset grant. In terms of the RDTI tax concession inquiry, there was a dearth of bioenergy organisations among the 69 submissions, and an absence of lobbying for a national biofuel mandate from the southern states of Australia.

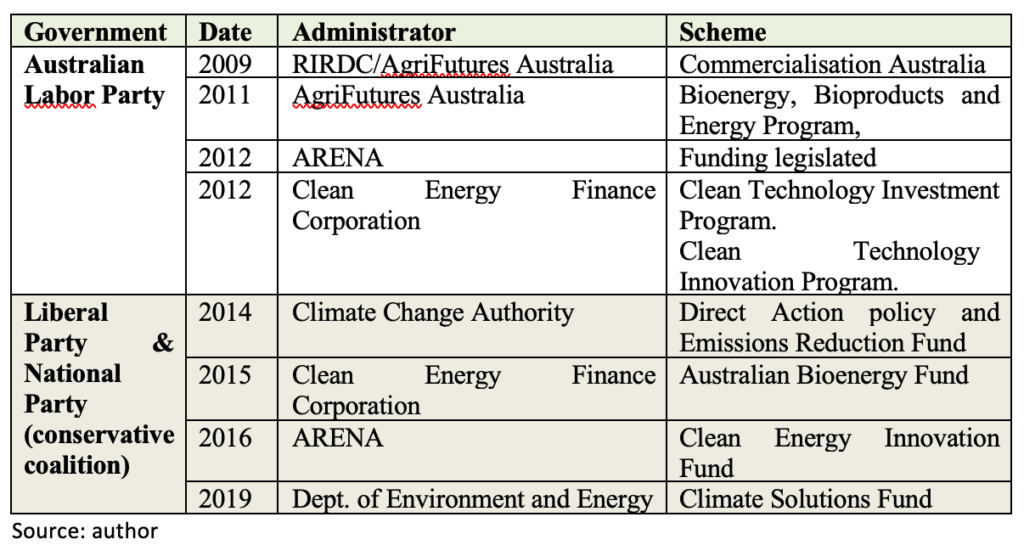

However, we found some indirect tax support for biofuels, such as the early stage investor tax incentive; tax subsidies such as the fuel tax credits; goods and services tax (GST) credits for fuel; and a lower fuel excise for aviation. These concessions provide moderate assistance to the biofuels industry. The federal energy schemes are summarised in Table 2. From the energy justice perspective, we found little evidence of inter- and intra-generational equity in the stalling and stopping of so many funding bodies, loan schemes and funds grants. For instance, grant schemes during the Labor government period, but now discontinued, include the $800 million Clean Technology Investment Program and the $200 million Clean Technology Innovation Program.

Table 2. Federal Energy Schemes

State policies and schemes

Since 2007 the state of New South Wales has mandated that volume fuel retailers sell 6 per cent ethanol in petrol and 2 per cent biodiesel in diesel. In 2017, Queensland legislation mandated for 4 per cent ethanol in petrol and 0.5 per cent biodiesel in diesel for retail fuel. There is a push to increase the scale of biofuels production to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transport. According to the International Energy Agency, a biofuel mandate is a fiscal policy lever that provides the market with a firm level of demand.

In terms of energy schemes from the states and territories, Victoria’s Sustainability Fund does not directly target biofuels. However, it demonstrates the energy justice principles of accountability, sustainability and intra- and inter- generational equity. While the biofuel mandates in Queensland and New South Wales might be helpful for reducing emissions in the transport sector, the energy justice principle of availability is transgressed as these mandates have not been legislated elsewhere in Australia.

The RenewablesSA initiative aims to promote the growth of South Australia’s renewable energy industry, and it generally demonstrates the energy justice principles of intra- and inter- generational equity and sustainability for renewables. Through access to federal funds, Northern Australia and the Australian Capital Territory show progress towards lower emissions. However, in terms of energy justice, Tasmania and Western Australia show poor accountability to their constituents in relation to carbon reduction and climate change, much less for biofuels. Transparency and accountability about energy is a community right.

Poor tax policies for biofuel innovation

Current policies relevant to biofuels reveal a lack of coordination between the state, territory and national governments that provide the scarce, albeit varied, renewable energy grant schemes.

At the federal level, the long delay from the 2016 research and development tax incentive inquiry to the present will have a negative effect. We await the Senate Economics Legislation Committee for its presentation of the report of the inquiry into the research and development bill 2019. The Senate report on the bill will not be settled until 2021.

A national co-ordination of grant schemes needs vital attention and reconsideration of a carbon tax. There has been a shift in research focus to wind, solar and hydrogen as sources of renewable energy, which is now at a scale not envisaged in 2007 (the ‘golden’ era of biofuels research). Wind and solar have emerged as the dominant sources of renewable energy in South Australia driven by grassroots interest. However, such a grassroots movement may not be as likely to facilitate biofuel innovation.

Consumers in COVID-19 lock-down had their spirits lifted by lower prices at the petrol pump. The irony is that most consumers did not drive anywhere, despite the ‘black gold’ rush to fill petrol tanks. However, low petroleum prices may not last and distract from the need in Australia for a coherent renewable energy policy that includes biofuels.

Further Reading

Diane Kraal, Victoria Haritos and Rowena Cantley-Smith, (2020) ‘Tax Law, Policy and Energy Justice: Re-thinking biofuels investment and research in Australia’, Australian Tax Forum, 35(1):31-58. https://www.taxinstitute.com.au/tiausttaxforum/tax-law-policy-and-energy-justice-re-thinking-biofuels-investment-and-research-in-australia

There is no any scope for Indian new enterpuner in MSME Sector to develop the Biofuel though there is a huge natural resources.