The rise of super-computing and improved data linking capabilities have presented new opportunities for policymakers to draw on ‘big data’ to guide social policy development. An example is the use of big data to underpin and drive recent ‘social investment’ policies in both Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Social investment thinking has a long history, representing a ‘Third Way’ between post-war (Keynesian) and (neo)liberal welfare states by layering neoliberal economics upon social democratic policies. It is driven by a move away from protective social spending and towards investment in future outcomes. As veteran journalist Colin James put it, ‘Spending is palliative and in the moment… Investment is constructive and for the future.’

The recent Aotearoa/New Zealand and Australian models are distinct from this longer history because they are enabled by big data, particularly in the form of large, linked administrative datasets arising from various social service domains. They are used to drive decisions about the targeting and volume of each country’s social welfare spend (cash transfers and social service delivery).

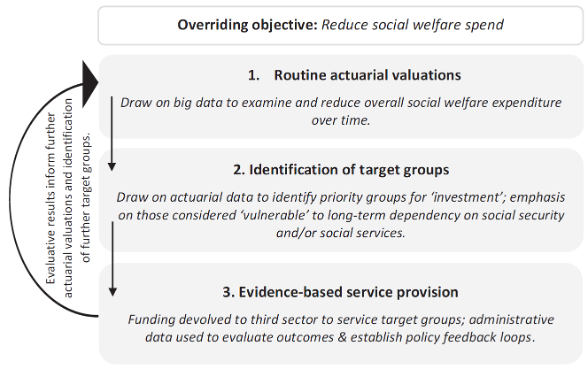

Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand’s social investment policies involve three core elements, as shown below, which draw on big data in different ways. There has been little critical attention paid to the use of big data under these policies. This was a core focus of our study, which involved a thematic analysis of policy documentation across both countries, including programme guidelines, media statements/press releases by policymakers, and Hansard debates.

Figure: Summary of social investment ‘cycle’ in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand (Source: Staines et al 2021)

A need for further critique and caution around big data under social investment

We uncovered a wellspring of support from policy advisors and politicians for the use of big data as evidence to guide social investment. Big data were regularly framed as enabling an overwhelmingly positive advancement in the pursuit of evidence-based policy; a move away from the ‘intuition’ driven policymaking of the past, and towards a new age of determining ‘what works’ and what doesn’t. However, while evidence is centrally important for moving beyond intuition in policy development, we found few acknowledgements of the limitations and potential harms of big data in the documents we examined.

First, we uncovered a deep and unreserved faith in actuarial valuations (calculated using big data) as high-level indicators of the ‘health’ of the welfare state. Evidence of reduced total expenditure over time is taken as ‘proof’ of the success of social investment — a view that is underpinned by the belief that all state-funded welfare is ‘debilitating’ rather than protective. There was little recognition of the fact that movement off the ‘welfare rolls’ may actually make things worse for many people; indeed, ‘positive fiscal and social outcomes are [often] fundamentally irreconcilable.’

Second, big data were regularly conflated with people’s ‘stories’ and ‘lives’. As (then) Aotearoa/New Zealand Deputy Prime Minister, Bill English, stated: ‘the data is just a story… [about] the 10,000 most challenging people of our community’. To the contrary, however, big data do not represent people’s stories and nor are they neutral and complete; they are more akin to non-stories omitting any link between cause and effect via a beginning, middle and end. In reality, big data under social investment mute people’s own stories, instead replacing them with political narratives that reimagine them as ‘fiscal liabilities’. This has tangible impacts, not only in terms of the ongoing stigmatisation of social security recipients, but also in terms of people’s abilities to narrate their own needs.

This relates to the third major theme arising from our study, which concerned the unintended impacts of collective targeting. Those identified as ‘at risk’, for example, are targeted for recruitment into various social programmes. However, those not targeted can lose access to important services. This occurred in Aotearoa/New Zealand when government funding for some services was restricted to adults with dependent children. Social service providers were left to either foot the bill themselves to deliver services to those who did not meet the new criteria, ask people seeking help to pay for services that had previously been provided free of charge, or deny service altogether.

Targeting under social investment also exposes some of the most marginalised groups in both countries to data privacy risks, simply because they are receiving social welfare support. As demonstrated under the Aotearoa/New Zealand model, this can result in demands being placed on non-profit service providers for identified personal information to ‘feed’ big data machinery, placing service users at risk of privacy breaches (including those drawing on services for sexual and domestic violence, for example). The thirst for data under social investment is thereby prioritised, while potential risks to social welfare recipients are largely ignored.

Finally, the emphasis on big data and the adoption of tools such as algorithms and predictive risk modelling (PRM) under social investment has particular implications for already disadvantaged communities. As sociologists Tahu Kukutai and Maggie Walter comment, wealthy colonial settler states have ‘long used population statistics as the evidentiary base for how Indigenous peoples are known and ‘managed’ through state policy approaches’. While useful in increasing the efficiency of services, algorithms often draw on historical data and can make human bias harder to detect. Given the over-representation of Indigenous populations in negative social statistics, there is a particular risk that the use of broad population-based data may exacerbate the tendency of governments to view Indigenous communities through the lens of what Walter describes as ‘five-D’ data; data that highlights disparity, deprivation, disadvantage, dysfunction and difference. In turn, this is likely to result in the further stigmatisation of Indigenous communities and inform the continued hypervigilance of settler states.

Implications and future strategies

There is no doubt that big data have potential to add value to policymaking. However, this is contingent on the ways in which these data are collected and deployed, including the level of transparency around limitations and risks. Under social investment in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand, it is overwhelmingly the case that big data are mobilised in ways that do not pay sufficient regard to their limitations, as well as the risks they pose to social welfare recipients. There is, we argue, a need to be more cognisant of these limitations, and to avoid the kind of data positivism that is apparent in current social investment discourses. This includes greater attention to avenues for legal recourse in combating decisions and outcomes arising from big data, greater regulation and protection of privacy, and further discussion around the promising developments of data sovereignty movements.

The value of big data as evidence under social investment needs to be more seriously questioned. We need to better understand the lens through which it enables policymakers to ‘see’ the world, what it misses, and what effects it produces. There is, after all, good reason to be suspicious of claims by social investment proponents that ‘more’ can be achieved with ‘less’. Rationalisation of social welfare spending is a long-standing objective of the liberal welfare model in countries like Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Following Molineaux (2017), we think it is fair to keep asking whether these examples of social investment are ‘just a warm and fuzzy cloak for seeking to shrink the state’ at the expense of those who remain in need of social protection. We might consider, therefore, whether big data are also being wielded as a new tool to muddy the waters of accountability, while the welfare state is further retrenched.

Further reading

Staines, Z, Moore, C, Marston, G &Humpage, L 2021, ‘Big data and poverty governance under Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand’s “social investment” policies’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 157-172.

Recent Comments