This four-part series explores the genesis of the idea of a ‘basic income’, how this evolved into a more broadly-based strategy for social improvement, the risks to job security and the welfare state, and the role of a basic income in overcoming them.

Part 1 examines the surprising origins of basic income.

From Speenhamland to poor law and welfare state

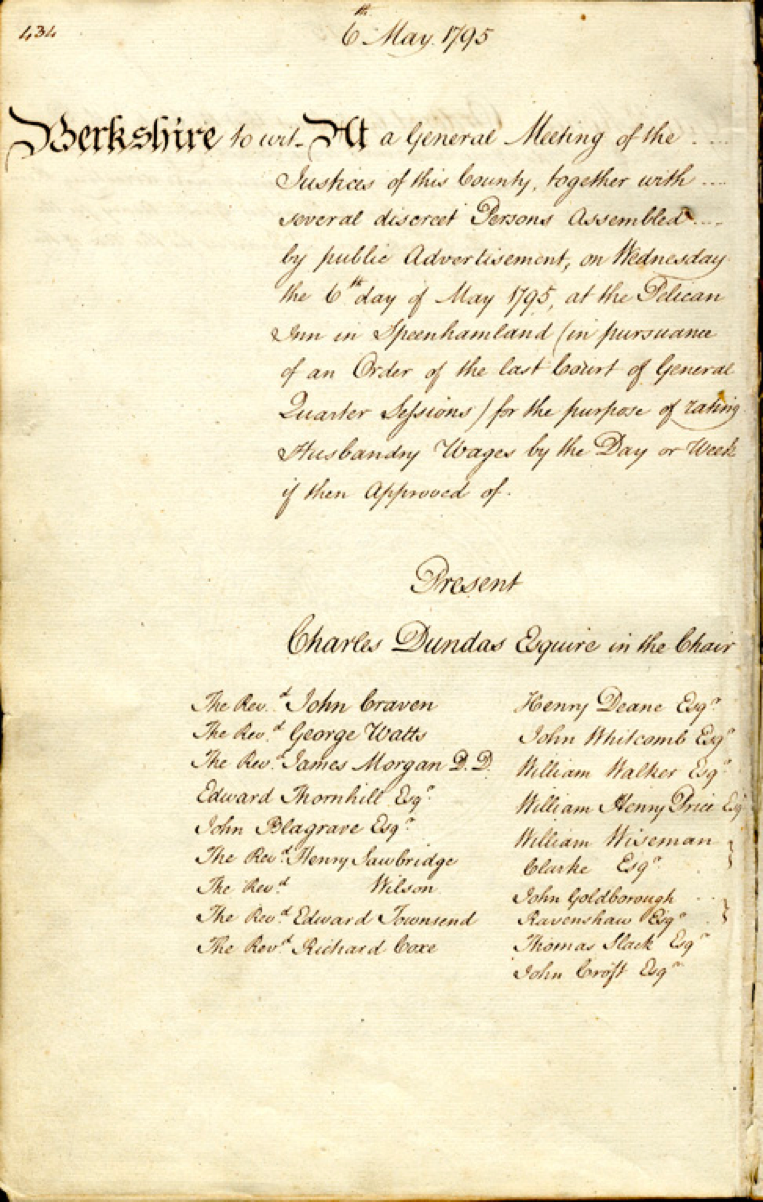

The first Basic Income scheme was introduced in Speenhamland, Berkshire in 1795, when the Napoleonic wars were underway, the French revolution was fresh in the minds of England’s rulers, and the industrial revolution was beginning.

Now that the idea has gained currency again, there is much to learn from Speenhamland and the Poor Law reform that followed it. The key lesson is that under capitalism, the labour market, politics and the welfare state are intertwined: changes in one impact on the other.

|

Box 1: Declaration of the local Magistrates at the Pelican Inn, Speen, Berkshire United Kingdom, 6 May 1795 “That it is not expedient for the Magistrates to grant that assistance by regulating the Wages of Day Labourers, according to the directions of the Statutes of the 5th Elizabeth and 1st James: But the Magistrates very earnestly recommend to the Farmers to increase the pay of their Labourers in proportion to the present price of provisions; “The Magistrates now present make the following calculations and allowances for relief of all poor and industrious men and their families, who to the satisfaction of the justices of their Parish, shall endeavour (as far as they can) for their own support and maintenance. When the Gallon Loaf of Second Flour, Weighing 8lb. 11ozs. shall cost 1s, then: every poor and industrious man shall have for his own support 3s. weekly, either produced by his own or his family’s labour, or an allowance from the poor rates, and for the support of his wife and every other of his family, Is. 6d.” (Source: Berkshire Record Office and the Victorian Web) |

The Speenhamland system

We can see from this declaration (see Box 1) in a pub in Berkshire that the idea of a Basic Income is not new. A cash benefit to meet basic living costs was paid out of council rates to thousands of farm workers (whether employed or unemployed). It was not universal (land-owners were not included), but this payment was widespread in the south of England.

Living standards of farm labourers in south of England were under pressure from high inflation driven by war, and a progressive loss of income from home production as new factories came into production across the north.

We can see from this proclamation that the local landlords (magistrates) were reluctant to impose minimum wages. Instead, they decided to use council rate revenues to protect the incomes of their workers.

The payments resembled modern income support, and even had their own equivalence scale to reflect the needs of families.

There was more. The landlords experimented with labour market programs for unemployed workers including subsidised private labour (‘roundsmen’), work for benefits (the ‘labour rate’), and (to a lesser degree) waged employment on public works (Block & Somers 2003, see Box 2).

All of these anti-poverty policies are familiar to us today.

It is no accident this first ‘basic income guarantee’ coincided with the onset of the industrial revolution. This was one last push by landowners of southern England to keep their rural workforce in the face of industrialisation.

Apart from Tory noblesse oblige, this was about preserving the old system of rural labour relations in the face of emergent capitalism.

|

Box 2: New wine in old bottles: income protection in England in the late 18th century 1. Minimum guaranteed income: The Speenhamland bread scale that provided specific amounts of aid in support of wages depending on the price of bread and the size of the family. 2. Seasonal unemployment insurance: During the winter months when agricultural work was scarce, some parishes provided unemployed farm workers and their families with a weekly stipend that varied depending upon family size. 3. Public works: Some parishes put the unemployed to work building roads or performing other types of work. Sometimes the supervision was done by public authorities and sometimes by private contractors. 4. Employer subsidies: Some parishes used poor relief funds to reimburse farmers and other employers who hired unemployed people. This was often called the ‘roundsman’ system because the unemployed workers would make the rounds of local employers. 5. Workfare: Some parishes allocated a certain proportion of unemployed people to each local employer with the idea that they would provide employment (at poor relief rates) instead of paying taxes for poor relief. This was referred to as the ‘labour rate’ system. 6. Child allowances: Many agricultural parishes provided a supplement to the income of male agricultural workers who had more than two or three children who were not yet of working age. 7. Workhouse: A minority of parishes required that unemployed people seeking relief enter a residential facility that imposed work requirements. Some of these facilities were publicly administered, and some were run by private contractors. (Source: Block & Somers 2003) |

But it didn’t last long

When the industrialists gained power in Parliament in the 1830s, they argued that the Speehamland system depressed wages and encouraged idleness.

These views were supported by new ‘dismal science’ of political economy (especially by Ricardo and Malthus). Together with the industrialists they argued for a ‘free market’ in labour (with workers unable to organise or vote!). This was the stimulus for infamous 1830s ‘Poor Law inquiry’.

Their arguments are strikingly similar to those against a Basic Income today, and we have reason to be sceptical:

‘In sum, the Speenhamland myth was created in the years of agricultural downturn to divert blame for a deep agricultural crisis away from government policy and toward the rural poor who were the major victims of the economic downturn.

‘Many of the specific complaints in the historical record about the corrosive effects of the [Speenhamland] actually centre on ‘roundsmen’ or others who were engaged in ’make work’ activities.

‘When public agencies create employment specifically with the goal of making recipients work in exchange for relief, supervisors usually find it difficult to elicit high levels of work effort because recipients know that they are not working in a real job.’

‘Since the decision taken by the government on Ricardo’s advice to restore the prewar parity of the pound intensified the rural depression, the mythology worked to cover up the first major policy failure of the new science of political economy.’

‘By shifting the blame for the problems on to Speenhamland and all its pernicious evils, the economic liberals successfully reframed the agricultural downturn into a problem of individual morality and an enduring parable of the dangers of government ‘interference’ with the market.’ (Block & Somers 2003)

The new poor laws: a ‘stoic determination to renounce human solidarity’

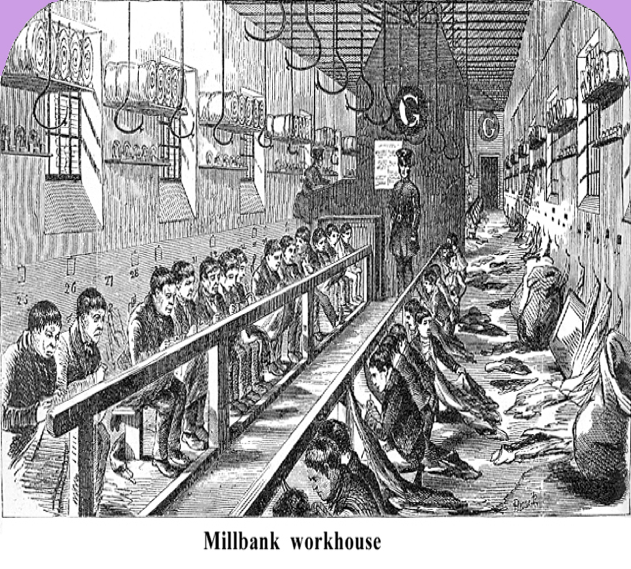

The result was a national ban on public relief for able-bodied individuals outside the horrors of the ‘workhouse’. This was the birth of social security principles we know today: ‘less eligibility’ (that benefits should always be much less than minimum wages), ‘deserving and undeserving poor’ (a duty to work for the able-bodied or ‘undeserving’, and higher benefits for ‘the deserving’ or those ‘unable to work’ due to a disability).

As Polanyi put it in his influential history of the industrial revolution:

‘It was at the behest of these [1832 Poor laws] that compassion was removed from the hearts, and a stoic determination to renounce human solidarity in the name of the greatest happiness for the greatest number gained the dignity of a secular religion.’

‘The abolition of Speenhamland was the true birthday of the modern working class, whose immediate self-interest destined them to become the protectors of society against the intrinsic dangers of the machine civilisation. But whatever the future held for them, working class and market economy appeared in history together. The hatred of public relief, the distrust of state action, the insistence of respectability and self reliance, remained for generations characteristics of the British workers.’ (Polanyi 1954, p102)

Charles Dickens chronicled the horrors of the 19th century workhouse:

‘At present, if a boy should feel a strong impulse upon him to learn the art of going aloft, he could only gratify it, I presume, as the men and women paupers gratify their aspirations after better board and lodging, by smashing as many workhouse windows as possible, and being promoted to prison.’

Source: Zimmer Lederberg E, ‘The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain’

Source: Zimmer Lederberg E, ‘The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain’

The take-home message of the new poor laws was that in the nascent capitalist system, decent minimum incomes – the ‘social minimum’ – would not be guaranteed by public relief alone, they must also be underpinned by decent jobs, skills, and wages.

From Speenhamland to Nixon

The Speenhamland system was of more than academic interest to modern policy makers. When Richard Nixon revived the idea of a basic income in his ‘Family Assistance Plan’, he was warned against it.

In the Nixon Administration, Daniel Moynihan was tasked with developing a ‘Family Assistance Plan’. As Moynihan recalled:

“In mid-April Martin Anderson, of [Arthur] Burns’s staff, prepared ‘A Short History of a Family Security System’ in the form of excerpts on the history of the Speenhamland system, the late eighteenth-century British scheme of poor relief taken from Karl Polanyi’s ‘The Great Transformation’.

“The gist of Anderson’s memo was that in that earlier historical case, the intended floor under the income of poor families actually operated as a ceiling on earned income with the consequence that the poor were further immiserated.”(Block & Somers 2003)

What happened next: two roads to betterment

By the end of the 19th century, the labour movement and social reformers realised they would have work on two fronts to end poverty and deprivation: the labour market and the State, unions and the vote.

Unions & industrial regulation

Source: Globalcitizen.org, ‘The history of International Women’s Day’

The vote and the welfare state

Source: Huffington Post

In Australia, by the end of the Second World War, these groups were successful in constructing the two pillars of the modern ‘social minimum’: labour market regulation and the welfare state.

In the labour market, this comprised:

- A high minimum hourly wage

- Full employment & regular working hours (for men)

- A high unionisation rate

In the welfare state it included:

- Free public education

- (Mostly) free public health services

- A robust public Vocational Education and Training system

- Age pensions

- An unemployment benefit safety net linked to a public employment service

- Family payments to prevent child poverty (both in & out of paid work)

It is often argued today that these social protections (at least for people of working age) can no longer be sustained in their present form; specifically that the social security system should now be replaced or supplemented by a Universal Basic Income. We explore the genesis of these arguments in Part 2 of this series.

This four part series is written based on the presentation, ‘From basic income to poor law and back again: can a UBI break the Gordian Knot between social security and waged labour?’, by Peter Davidson at the Australian Social Policy Conference at UNSW on 27 September 2017. Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4.

Pingback: From Basic Income to Poor Law and Back Again - Part 2: Whither the Welfare State? - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Pingback: From Basic Income to Poor Law and Back Again - Part 4: Designing a Viable Basic Income - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Pingback: From Basic Income to Poor Law and Back Again - Part 3: Renewing the Social Minimum - Austaxpolicy: The Tax and Transfer Policy Blog

Interesting thoughts, I just read all four parts and just wanted to comment on this first post. Polanyi’s point was that Speenhamland was reactive, was in contradition to other policies oriented towards establishing a free market system. For instance, the settlement act, was loosened in 1795, abolishing parish serfdom and allowed the poor to move between parishes, thereby going to were labour was required. Depopulation on the countryside thus accelerated and Speenhamland was not a reaction against that, it was a universally advocated race to the bottom because there was no incentive to work, prior distinctions between workman and pauper upheld in the previous institutional system were now meaningless, and all the sudden if you were not wealthy, you were poor. Workers didn’t have to work, and they would be fed (right to life); owners didn’t have to pay and they would get labour. A system built on such reactionary humanitarianism is built for moral depravity. The government of the conservatives or the Wigs never thought to again make land common, to reverse the enclosures and repopulate rural areas. The British instead colonised large parts of the world, used these colonise as agricultural peripheries and prevented their industrial development in most cases, Australia being a limited exception. Thus, I am quite baffled by the fact that you find the roots of Australia’s potential UBI income in this context of British history. Isn’t it more obvious to point to the Harvester’s case, in which justice Higgins famously made the argument for a living wage: ‘the power of the employer to withhold bread us a much more effective power than the power of the employee to refuse to labour. Freedom of contract, under such circumstances, is surely misnamed; it should rather be called despotism in contract.’