Would you and your mates cancel a celebration if the price of your usual drink went up while the prices of other alcoholic beverages remained the same? Most likely, no. Paradoxically, the current system of regulation is predicated on the assumption that you would.

Tax is the main means by which the Australian Government tries to influence alcohol consumption. Australia has four different tax regimes (for beer, spirits, ready-to-drink beverages and wines) and two different modes of taxation (excise duty and equalisation tax). Beer is subject to eight different excise rates, and brandy is taxed differently from other spirits, while wine has its own special tax arrangements. As a result, there is no effective policy tool; instead, policymakers have to engage multiple diverse artificial and politically expensive processes to regulate one product.

Alcohol abuse imposes an enormous health burden on the community. The acute burden of abuse is felt mainly by the young, a disproportionate number of whom are killed through accident and misadventure. Getting alcohol policy right means getting the system of taxation right. While the complexity of the Australian system of alcohol taxation has been criticised for decades, our new study shows that our tax system is incapable of delivering an effective policy response to the problem of alcohol use by young people.

We found the 2008 ready-to-drink beverages tax hike missed its target

During 2008 and 2009, in response to a growing concern that ready-to-drink (RTD) beverages were encouraging a culture of binge drinking by adolescents, the Australian Government increased the tax on RTDs by 70% to specifically target adolescent drinking. Our new study shows this massive tax hike did not affect alcohol consumption of those under 25 years old (the targeted age group). Instead, the tax reduced drinking among those aged 25 – 69, reducing their average daily consumption of standard drinks by 8.9% from 2010 to 2018.

The age group under 25 did not respond to the tax hike because we argue young people have no problem switching to a different product if their preferred drink increases in price. The alcohol industry anticipated the switch and provided further price and marketing encouragement for it. We also show that the 29% wine equalisation tax rebate of 2004 actually increased drinking among those under 25. The rebate was effectively a subsidy, propping up the production of cheap wines.

These observations show that the drinking of young Australians is sensitive to the presence of the cheapest drinking options. Therefore, alcohol tax policy should avoid focusing on particular types of beverages. A better approach would be to introduce a floor price on alcohol per standard drink, as recently pioneered by the Northern Territory, or replace the current taxation system on alcohol with a uniform volumetric tax per standard drink, applied across all alcohol products.

How do we know the tax is not working?

The innovation of our study is that, unlike previous studies, which compared alcohol consumption before and after the RTD tax hike, we employ quasi-experimental techniques that allow us to separate the effect of the tax on different age groups. We also use individual-level data from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey rather than aggregate-level data. The basic logic of our estimation approach is clarified in the figure below.

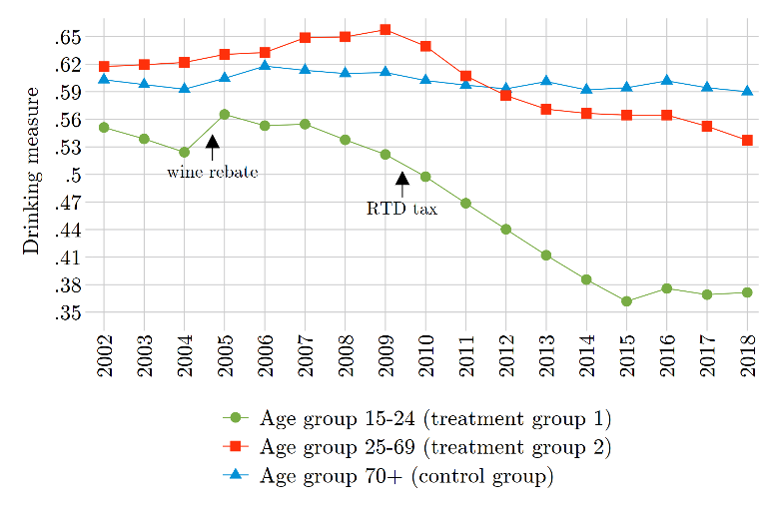

Figure 1: Trends in drinking: three age groups, HILDA 2002-2018

Source: Alexeev and Weatherburn (2021)

The figure shows the Australian national annual drinking trends with population broken into three age groups. The age group above 70 (blue line) was unaffected by the RTD tax. We use it as a comparison group. The effect of the RTD tax on the age groups 25 – 69 (red line) is easily distinguishable. The time trend for this age group goes up, right before the tax increase, and then goes down. Drinking by the age group 15 – 25 (green line) generally follows a downward trend.

The first arrow points to a visible rise in adolescent drinking in 2005 – the consequence of the 29% wine equalisation tax rebate of 2004. The second arrow points to an area where the RTD tax should have had an effect. The downward trend continues without any change, showing no impact on drinking. The general downward trend is in line with other studies that show a global reduction in drinking among young people. Therefore, an approach that compares young people drinking before and after the tax gives the erroneous impression that the RTD tax reduced drinking by young people.

Our study separates the tax effect from the general downward trend. On a technical side, we implement a difference-in-difference strategy and verify the common trend assumption by estimating a distributed lag difference-in-difference specification and testing that the coefficients prior to the tax are jointly statistically indistinguishable from zero. We also complement our difference-in-difference specification with the comparative interrupted series analysis, which allows for flexible pretreatment trends. Therefore, we are able to show the RTD tax reduced alcohol consumption among those aged 25-69 but had no effect on on those under 25.

A more sophisticated approach needed

In introducing the RTD tax, the Australian Government was obviously concerned about protecting young Australians. We hope that our findings persuade the Australian Government to take a more sophisticated and effective approach to alcohol taxation. The current taxation system benefits political lobbyists at the expense of the public health of Australians. It benefits lobbyists because every change in regulation, including minor technicalities, is subjected to extensive debate in different political and regulatory bodies. Therefore it is much easier to maintain the status quo (where different taxes regulate one product) than to implement better evidence-based public policy. This resistance to change might be why only the Northern Territory (the least populated Australian jurisdiction with the least cumbersome political structure) is the pioneer in implementing Recommendation 71 of the Henry Tax Review that ‘[a]ll alcoholic beverages should be taxed on a volumetric basis, which, over time, should converge to a single rate.’

Hey there,

Let us know if you have any questions about the post.

Sergey

Re your last sentence: the States and Territories cannot implement excise (volumetric taxation). The States’ taxation of alcohol through franchise fees was deemed unconstitutional in 1997. The NT Government applies the minimum floor price as a condition of its liquor licensing arrangements so it is linked to liquor licensing fees.

Dear Glenys Byrne

Thank you for your comment.

I apologize for any potentially incorrect interpretations of the Australia institutional details.

I hope future readers will read your comments in addition to the article to have a better understanding of the problem.

Please add more comments to this post.

Regards,

Sergey

Hey there,

Let us know if you have any questions about the post.

Please consider reading the published version

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103399

Sergey