Changes to superannuation guarantee have yet again been included in the 2018 Federal Budget. Since the introduction of the superannuation guarantee over a quarter of a century ago, superannuation has been subject to continuous policy tweaks, with major overhauls occurring in 2007 and 2017. As the system matures and the objective of superannuation ‘to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the age pension’ to be enshrined, the adequacy of retirement savings will once again dominate policy debates.

While debates about increasing the superannuation guarantee rate to 12% attract headline attention, discussions on voluntary savings in superannuation are limited. In a recent article in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues, I investigated this important aspect of retirement savings amongst employees using ABS and HILDA data from 2005 to 2010.

Voluntary savings in superannuation are a great addition to retirement savings on top of compulsory employer contributions. Given the low rates of savings before superannuation contributions were made compulsory in 1992, and after that the high rates of forced savings in superannuation, it is perhaps not surprising that voluntary savings is low. The percentage of employees who have a salary sacrifice arrangement is in the mid-teens, while that for post-tax contributions is only slightly higher. The pattern remains unchanged despite changes to superannuation policy. In my research, I examined what determines voluntary savings in superannuation.

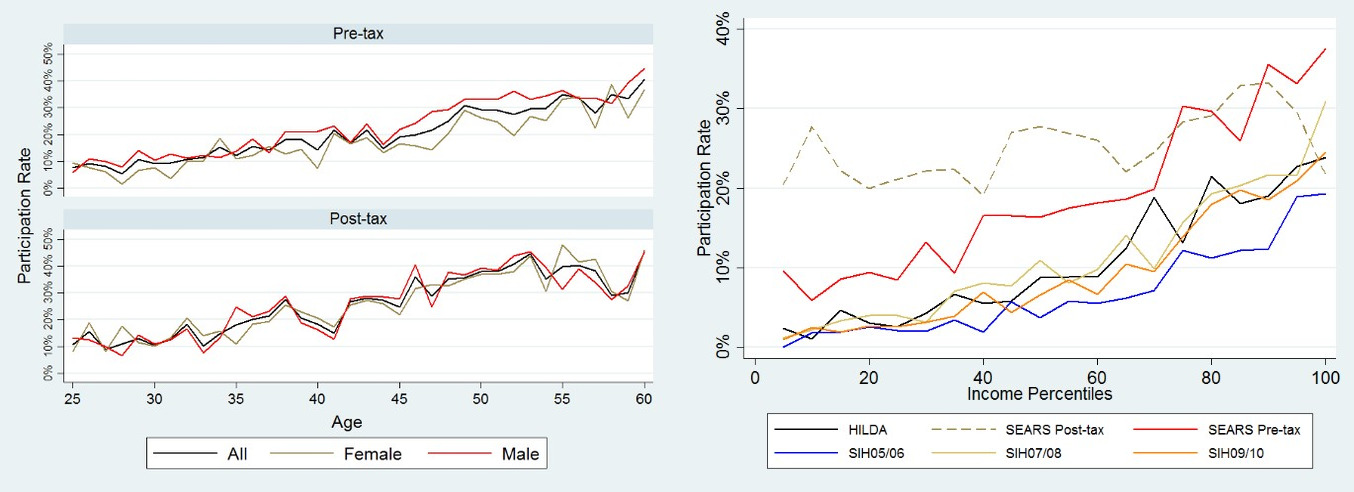

Figure 1 breaks down the participation in voluntary savings in superannuation by gender, age, and income. Both pre-tax (salary sacrifice) and post-tax savings saw an increased participation as superannuation fund members age, but only the participation in salary sacrifice grew along with members’ incomes. Gender differences, on the other hand, are not as apparent.

Figure 1: Participation in voluntary savings in superannuation

Data source: ABS data: Survey of Employment Arrangements, Retirement and Superannuation (SEARS, 2007, pre- and post-tax contributions), Survey of Income and Housing (SIH, 2005/06, 2007/08, 2009/10, pre-tax contributions only), and HILDA (2010, pre-tax contributions only) data

The determinants

In my research, a number of factors were identified to influence voluntary savings decisions. In particular, older, financially secure individuals who can afford to save for retirement are more likely to make additional savings arrangements. Non-participants—often young, low income earners, or workers without stable jobs—are more likely to face competing priorities such as repaying debt for education, mortgage, or precautionary savings. Indeed, when ABS survey respondents were asked why they do not make additional contributions to superannuation, affordability issues such as “cannot afford” or “paying mortgage” were the top reasons.

My study also shows that women and people with lower education qualifications were not directly disadvantaged when other factors were taken into account. The gender and education gaps in superannuation savings are mainly the result of women and less well-educated people generally earning lower incomes. High income earners make substantially more concessional contributions (salary sacrifice) as this reduces their tax liabilities. This suggests that government tax incentives have a role in the voluntary savings decision. However, low income earners are not as actively involved in post-tax contributions to take advantage of government co-contribution scheme, mainly due to affordability.

In addition to observed characteristics, behavioural patterns are also good indicators of retirement savings. Superannuation fund members who intend to retire early and rely on superannuation to do so are more likely to make additional savings in super. Good planning practice, especially retirement planning, and good saving habits are positively associated with savings arrangements as well.

A contribution of this study is that the analysis revealed a strong substitution effect between pre- and post-tax savings decisions. Members of a super fund tend to choose one or the other saving channels, rarely making voluntary contributions both concessionally and non-concessionally. This suggests that individuals choose the most suitable pathways to accumulate wealth for retirement. Although intuitive, this relation has never been formally identified.

Implications

Separately analysing data from different years, I identified same factors that predict voluntary saving behaviours. It indicates that the pattern of voluntary savings in superannuation does not dramatically change over time. The take-home messages are:

Firstly, low participation in voluntary savings in superannuation is worrying to the government, given that the federal government is changing the narrative of retirement funding to emphasise self-funded retirement. The low participation rate may reflect the belief that compulsory savings are the benchmark for retirement savings, and individuals are therefore secured for retirement without needing additional savings. Indeed, 17% of ABS survey respondents, who were not making voluntary savings in superannuation, believe that they are sufficiently covered for retirement by employer contributions or their spouse’s superannuation, and further 15% have never thought about whether it will be enough. From a comprehensive policy perspective, it may be beneficial to raise more awareness about retirement savings gaps.

Second, low income earners and high income earners have very different participation patterns. One of the motivations of high income earners to make voluntary savings through superannuation is to reduce tax liabilities. This incentive does not apply to low income earners. Despite other government efforts (such as government co-contributions, spouse contribution tax offset) to incentivise more savings, low income earners often are unable to do so because of competing concerns such as buying a house. People prioritise the latter because owner-occupier property does not attract a capital gains tax at disposal and is not assessed in the Age Pension assets test. To this end, the low income superannuation tax offset is an effective start in building more retirement savings for low income earners. While superannuation is the main retirement wealth-building vehicle, any policy change to encourage voluntary savings needs to have a holistic view. It must account for all areas of household wealth and retirement incomes.

Third, the widely recognised gender retirement savings gap needs to be addressed at its root cause. That is, unless the gender earnings gap is closed, women will remain disadvantaged in retirement savings, despite behaving no differently to men in similar circumstances.

Lastly, education on financial planning and saving could help shape working-age population behaviour in saving for retirement. Incentives that promote regular savings would also play a critical role.

Jun Feng, 2018. “Voluntary Retirement Savings: The Case of Australia,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Springer, vol. 39(1), pages 2-18, March.

Recent Comments