The 2021-22 Federal Budget marks the final main instalment in the Federal Government’s fiscal policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic, barring any mishap in which there is a severe outbreak before most of the population has been fully vaccinated. So, it is timely to assess fiscal policy in the COVID-19 era. Five lessons are drawn for the future. This contribution to the TTPI Budget Forum summarises a more detailed note available here, which in turn previews a forthcoming working paper that will present the complete (and updated) study.

JobKeeper

The COVID fiscal response was led by JobKeeper, which ended after 12 months in March 2021. The JobKeeper payment per employee for businesses experiencing substantially lower turnover provided a wage subsidy for employees who remained active, while it provided a superior alternative to the JobSeeker benefit for employees who became inactive.

Treasury found that JobKeeper largely achieved its three main aims: (i) to keep workers in an unbroken relationship with their existing employer; (ii) to help businesses remain viable; and (iii) to compensate workers and business owners for income losses from restrictions. However, JobKeeper over-achieved in pursuing its third aim of compensation in three cases.

First, JobKeeper over-compensated inactive part-time employees who received more from JobKeeper than their usual wage. This removed their incentive to find active employment.

Second, JobKeeper over-compensated businesses which experienced sufficiently low turnover to qualify in the eligibility testing month of April 2020, but whose turnover then recovered when some restrictions were lifted in April and May. Such businesses continued to receive JobKeeper through to September, providing them with windfall profits.

Third, JobKeeper over-compensated businesses which only narrowly qualified for it under the loss of turnover test, yet received payments at the same level as businesses who experienced more severe losses of turnover. An analysis based on an ‘average’ business constructed using ABS data (see page 2 here for detailed analysis) shows that when economic restrictions were lifted, most smaller businesses had an opportunity to make higher profits by restraining turnover to 70 per cent of normal to remain eligible for JobKeeper, instead of returning to full operations and losing JobKeeper. Unlike the first two cases of over-compensation, this third case of over-compensation was not fully addressed by the changes applied to JobKeeper from October 2020.

Lesson 1. To limit profiteering, compensation payments should be better targeted at businesses affected by restrictions (for example, by varying payment rates by industry) and lower payments should be made to businesses who only narrowly qualify for support.

Assessing the fiscal stimulus

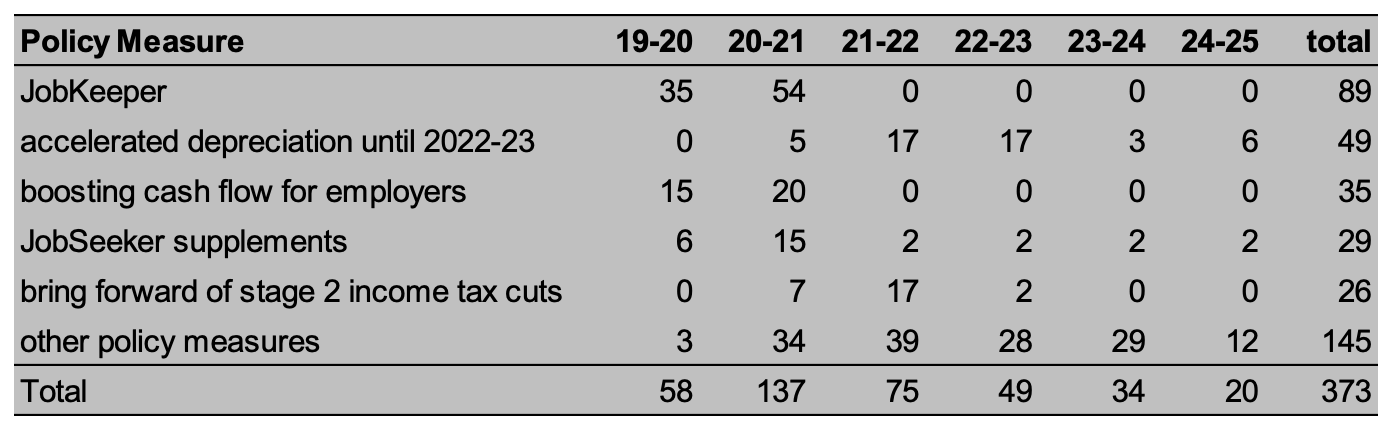

The total budget cost of the COVID-era fiscal measures, including JobKeeper, was $373 billion (see Table 1). To assess whether this massive fiscal stimulus was appropriate, three alternative scenarios were simulated using a prominent macro-econometric model of the Australian economy. Following new development work in 2020, this model has more detailed, elaborate fiscal policy modelling than other Australian macro-econometric models.

Table 1: Budget cost of COVID-era fiscal policy measures ($ billion)

Sources: 2020-21 and 2021-22 Federal Budget documents; ABS quarterly national accounts

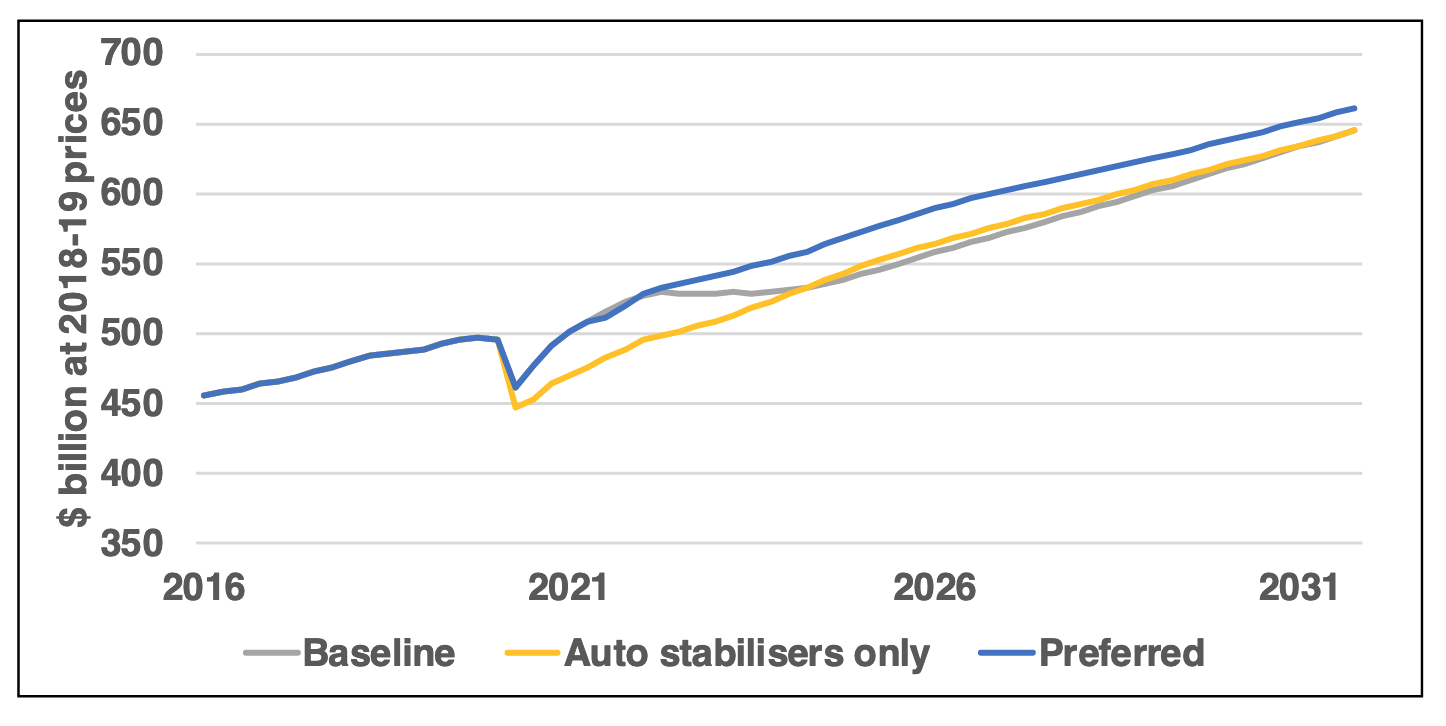

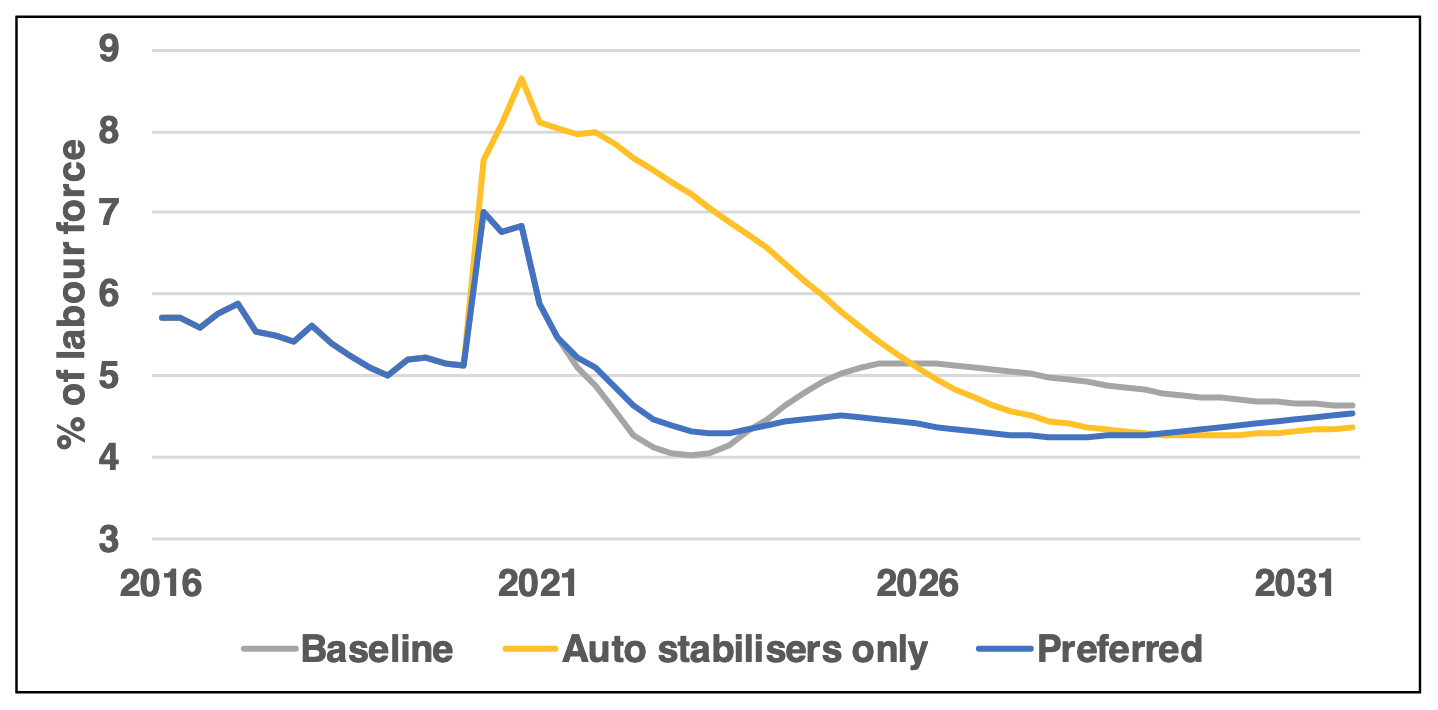

The Baseline Scenario incorporates the COVID-era fiscal stimulus while the Automatic Stabilisers Scenario does not. The modelling results show that the fiscal stimulus resulted in better short-term outcomes. Real GDP is an average of 5.7 per cent higher from 2020-21 to 2022-23 (see Chart 1) and the unemployment rate is an average of 3.0 percentage points lower from 2021 to 2023 (see Chart 2).

Lesson 2. The massive fiscal stimulus of the COVID era greatly improved short-term outcomes for unemployment and GDP compared to relying only on the automatic stabilisers to counter the economic downturn.

Chart 1: real GDP

Chart 2: unemployment rate

However, even better outcomes are achieved in the Preferred Scenario. This scenario largely ends the fiscal stimulus from 2021-22 following the end of most economic restrictions (other than on international travel), reducing it from $373 billion to $257 billion. In the Baseline Scenario, over-stimulation of the economy leads to inflation, higher interest rates and swings in unemployment from 2022 to 2024 (see Chart 2). In the Preferred Scenario, unemployment stabilises more quickly near a sustainable rate of 4.5 per cent (see Chart 2).

Lesson 3. The fiscal stimulus should not extend beyond the end of the restrictions, to avoid over-stimulation from fiscal policy having to be countered by tighter monetary policy, resulting in macroeconomic instability.

Modelling potential tax reforms

The Preferred Scenario also includes two modest tax reforms so that there are lasting economic benefits from COVID-era fiscal policy.

The first reform makes permanent the temporary program of full expensing of business investment in plant and equipment (the main program of accelerated depreciation referenced in the Table) and extends it to all companies. This stimulates higher investment, raising productivity and economic activity.

In the second reform, the Federal Government encourages a nationwide switch from taxing housing transactions to taxing housing land, as urged by the New South Wales Government. The removal of stamp duty on conveyancing means that households are no longer discouraged by the tax system from moving to optimise the location and nature of their housing to their employment opportunities and the stages of their life cycle. Hence, there is a better allocation between households of the $7.4 trillion stock of residential buildings and land.

These tax reforms lift real GDP about 6 per cent above its baseline path in 2024-25 and 2025-26, and 3.4 per cent above in the long term (see Chart 1).

Lesson 4. To generate lasting gains, full expensing of business investment in plant and equipment should be made permanent and extended to all companies, and the Federal Government should co-ordinate a nationwide switch from taxing housing transactions to taxing housing land.

Goal for net debt

The Budget envisages that government debt issued to fund the COVID fiscal stimulus will remain outstanding into the medium-term. As a result, while in the 2019-20 Budget government net debt was projected to fall to zero in 10 years, in the 2021-22 Budget it is projected to be equivalent to 37 per cent of GDP at that time.

This revised plan has been influenced by reasoning based on the current low level of interest rates. The reasoning assumes that it is safe to borrow as long as debt rises no faster than GDP. In that case, as long as interest rates on government debt (around 2 per cent) remain below the growth rate of nominal GDP (around 5 per cent), the interest cost from debt is lower than the borrowing capacity it generates.

However, this reasoning that debt is a fiscal advantage has two shortcomings. First, the reasoning relies on interest rates remaining very low by historical standards. This may appear likely now, but is far from certain, raising concerns over risk management.

Second, the reasoning assumes that higher debt will not eventually lead to a higher risk premium. A number of EU countries have been caught out by that in the past decade.

Lesson 5. The Federal Government should plan on making more progress in winding back its debt. Specifically, it should ‘bank’ the gain in projected revenues when its very pessimistic assumption for iron ores prices is very likely revised up within 12 months.

Other Budget Forum 2021 articles

Structural Changes, but No Sustainability Reset, by Miranda Stewart.

This Was an Election Budget on Steroids, by John Hewson.

The Volunteer Workforce Is Key to Achieving Budget Priorities, by Sue Regan.

Looming Tax Cuts Prevent Genuine Expenditure Reform, by Maria Racionero.

Australia’s Planned Patent Box: A Means of Stimulating Innovation? By Sonali Walpola and Tracy Wang.

Could It Pack a Punch? Maybe, but There’s a Lot at Stake: The Reactivation of the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle, by Alex Evans.

Don’t Shoot in the Dark: Business Support in the Australian Budget, by Andrés Bellofatto, Begoña Dominguez and Jorge Miranda-Pinto.

Chris A response to your concerns about debt.

“This revised plan has been influenced by reasoning based on the current low level of interest rates. The reasoning assumes that it is safe to borrow as long as debt rises no faster than GDP. In that case, as long as interest rates on government debt (around 2 per cent) remain below the growth rate of nominal GDP (around 5 per cent), the interest cost from debt is lower than the borrowing capacity it generates.

However, this reasoning that debt is a fiscal advantage has two shortcomings. First, the reasoning relies on interest rates remaining very low by historical standards. This may appear likely now, but is far from certain, raising concerns over risk management.

Second, the reasoning assumes that higher debt will not eventually lead to a higher risk premium. A number of EU countries have been caught out by that in the past decade.”

The Australian government being a sovereign currency issuer, that has a free floating exchange rate, sets its interest rates , has no debt in a foreign currency DOESN’T need to borrow. It can issue bonds if it wants to, however it can always make repayments in its own currency no matter what, as it’s the issuer of its currency. It can never default. Those countries with debt problems weren’t sovereign currency issuers. Many debt problem countries were pegged to another currency or were in the Eurozone.