Well over three months into a hastily implemented lockdown, India announced and has stepped into ‘Unlock Two’ starting 1 July 2020. The evident lack of planning in getting into a lockdown in such a large country meant that it ended up needing three extensions. This has already taken its toll on the Indian economy, as it almost grinded to a halt. Economic challenges are staring the nation in the face as never before.

While most countries announced easing off lockdowns after managing to flatten the curve and as the infection rates started trending downwards significantly, India has chosen to ease the lockdown at a time when the infection rates in this part of the world are climbing faster than ever before, and has yet to peak. At the time of writing, India is near the top worldwide in terms of coronavirus positive cases. Thus, the new challenge seems to be how to ‘live with the virus’ when the country confronts the uncertainties emanating from its exit strategy (or lack of it). It is in this context that we consider the political approach to the COVID-19 policy response and assess how effective it is in standing up to the challenges faced by the nation.

On 12 May, the Indian Prime Minister announced a ‘mega’ stimulus package of INR 20 trillion (US$ 265 billion), which is 10 per cent of the country’s GDP. This was a long awaited announcement for a nation whose economy was already significantly slowed down towards an impending recession. The announcement was made by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on national television, where he pitched for the country to work towards an atmnirbhar bharat (‘self-reliant India’), by going ‘vocal for local’ through measures taken under the proposed LLLL (Land, Law, Liquidity, and Labour) headings. The total package of INR 20 trillion was stated to include various liquidity measures previously announced by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in February, March and April and the earlier ‘fiscal package’ announced by the Finance Minister on 27 March.

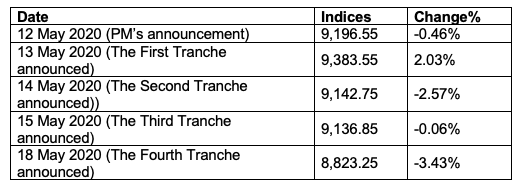

The stimulus package was a major announcement and caused as spike in the stock market, with the benchmark NIFTY Index going up by almost 200 points (Table 1). The NIFTY index serves as an indicator of the sentiments of the public and the business community at large. But as the details of the package were revealed by the Finance Minister in four tranches over the ensuing week, the enthusiasm that had built up started to dissipate, with the NIFTY Index ending up at a low of 8,823 on 18 May (from a high of 9,384 on 13 May).

Table 1: The High Frequency Variations in NIFTY Index

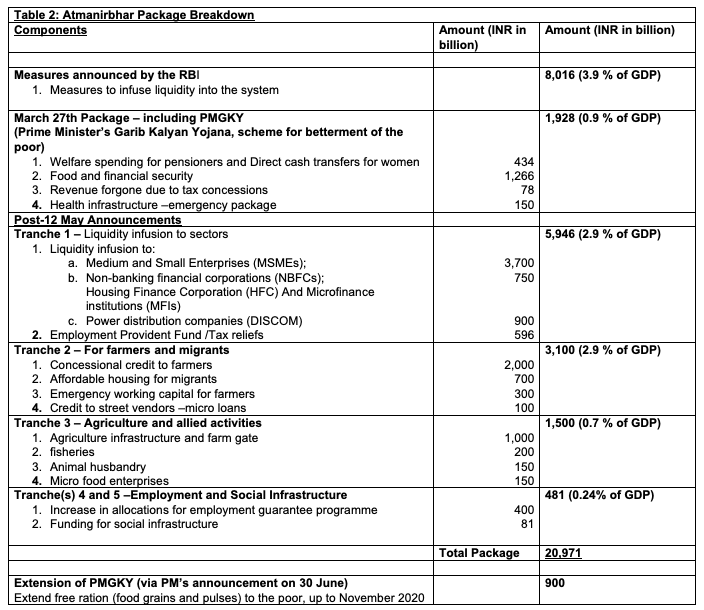

Details of the 20 trillion package

So, how large a boost does the mega stimulus package give the Indian economy? The key elements of the package are summarized in Table 2.

Source: Government Reforms and Enablers – Atmanirbhar Bharat; Prime Minister’s Televised Address on 30 June 2020.

Few fiscal measures in the package

An infusion of spending power into the economy is the only way to help it recover. Unfortunately, the Government in its mega stimulus chose to remain on the path it took with its initial approach, and focused almost entirely on liquidity measures. Liquidity measures accounted for the bulk of the INR 11.0267 trillion announced by the Finance Minister over the week following Prime Minister’s announcement on 12 May.

Many consider that the Government should have learned from the failure the first time around when the rate cuts initiated by the Reserve Bank of India did not produce the desired effect. Without any major increase in borrowers, even with the substantial decrease in lending rates, commercial banks chose to park their monies with the central bank using its reverse repo window – it went up from INR 3 trillion on 27 March to INR 8.4 trillion by the end of April.

Only a small fraction of the package is an actual infusion of money into the economy to boost spending power, being in total INR 662.5 billion. This includes tax refunds and provident fund rebates which amount to INR 627.50 billion, leaving only INR 3.5 billion in direct spending. The tax refunds and rebates do not mostly reach the most needy in society. Even the expenditure of INR 3.5 billion does not reach the hands of the needy as a direct cash transfer to families, but instead accounts for the allocations of cereals and grams for families.

On 30 June, the Prime Minister further announced a INR 900 billion extension of the PMGKY scheme (which provides free ration to over 800 million people) by another five months until the end of November 2020.This is in addition to the INR 20 trillion package.

Overall, the whole package is much smaller than it appears. Even a cursory glance at the detail reveals a completely different picture. The projected 10 per cent of GDP is a chimera. The actual fiscal cost for the Government is only about INR 1 trillion, or about 0.75 per cent of GDP as stated by Rahul Baoria, Chief India Economist at Barclays Bank. After the huge expectations about the Prime Minister’s stimulus package, reactions were rather scathing. Analysts at the global research firm AB Bernstein said that ‘the need to announce measures that add up to this top down number made the entire package aimless’, and that overall, they saw it as a ‘lost opportunity.’

The Government seems to have taken a cue from other big announcements of mega relief packages from across the world, notably the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, which have relied heavily on financial institutions and ultimately led to smaller spending than expected.

The deficit is a concern, but extraordinary times need extraordinary measures

The impact of the COVID19 pandemic on the Indian economy which was already on crutches has been devastating. Unemployment rates in India were at a 40-year high even before the start of the pandemic, and the economy was showing a serious downward trend. India was in need of a stimulus package from the Government even before COVID19.

Since the pandemic, a massive number of people have lost their means of livelihood. By various estimates, from 82 to 94 per cent of the workforce in India is employed in the unorganised sector. There have been huge cuts in wages across the board. If sales of automobiles and consumer durables are anything to go by, even a conservative estimate suggests that there may be a loss of more than 80 per cent of demand in the economy. The impact of COVID-19 and the consequent lockdown has been brutally severe. The plight of the hapless migrant workers should have served us as a grim reminder that even a deadly virus can be no match for hunger.

The Government seems to be concerned, perhaps rightly, about the fiscal deficit rising. But these are extraordinary times, and one cannot help but wonder if that is the right strategy. If tax revenue falls due to collapsed demand there would be a massive rise in fiscal deficit anyway. Tax collections never exceed government expenditure in general in India, and selling assets is not an option at this hour of need.

The only plausible alternative for the Government is a direct monetization of the deficit. This seems to be a route that the Government is reluctant to take the moment, but it may be forced to consider it in future. In such uncertain times, it remains to be seen if there is a push in taking loans (even if it is collateral free). The central bank’s measures (in March and April), with its repo-rate linked loans, failed to stimulate borrowing. Entrepreneurs, traders and farmers take loans from banks to finance production and obviously they would only do that if they are reasonably confident about selling their product. The lockdown, and its implementation without much planning, doused that confidence. Almost every rating agency (Fitch, S&P, Moody’s, IMF, and the World Bank) is downgrading India’s growth rate projections. It remains to be seen how much demand this ostentatious ‘mega’ package is able to stimulate and how effective it will be in mitigating the hardships and pain of the average Indian.

Recent Comments