This post was originally published as part of the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Policy Brief series.

After some years of stasis, superannuation tax reform was back on the agenda in 2016. Not since the Howard-Costello changes in the 2006- 07 Budget has there been such a substantial amount of superannuation reform. However, the 2016 changes go in the opposite direction of the Howard-Costello reforms by tightening tax concessions received by those on highest incomes.

For a weighty and complex package of legislative changes, the reforms result in minimal savings – approximately $3 billion over the forward estimates – while doing little to address underlying inequities in the system. As the Government itself notes, 96 per cent of individuals in the superannuation system will be unaffected or be better off as a result of the package. This gives some indication of the very modest changes introduced.

The new objective of superannuation is to, ‘provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the Age Pension.’ This purpose does not attempt to address the broader question of what standard of living Australia’s retirement income system provides, a point which has been debated among superannuation industry representatives.

The current system: overview

Retirement savings may be taxed at different points in time: when a person contributes; on the income from those earnings in the fund; and when funds are withdrawn. Australia’s superannuation tax system is what is known as a ‘Tax-Tax-Exempt’ (TTE) system, which is unchanged by the 2016 reforms.

Under Australia’s TTE system, tax of 15 per cent is levied on most contributions to superannuation funds and on income earned in the fund. Generally speaking, withdrawals of superannuation are completely tax exempt, following the Howard-Costello changes of a decade ago.

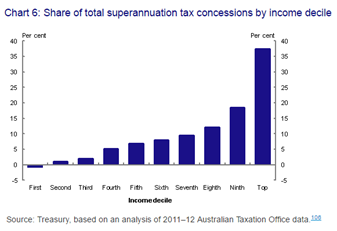

Like any flat rate of tax, superannuation tax on contributions and earnings of 15 per cent is most concessional for those taxpayers on the highest incomes (who would otherwise face the highest marginal tax rate on their income). Treasury estimates that over 50 per cent of the tax concessions in superannuation are received by the top 20 per cent of income earners. An exception to the flat rate of 15 per cent tax is the 30 per cent contributions tax, levied on individuals with incomes of $300,000 and above.

Currently, employers are required to pay 9.5 per cent of employee income into superannuation. This compulsory minimum level of contributions is known as the Superannuation Guarantee and applies to most employees (although not below a minimum threshold of hours).

The level of the Superannuation Guarantee will remain at 9.5 per cent until 2025-26, when it is scheduled to rise to 12 per cent. Whether or not this level of superannuation savings is sufficient depends on many variables, including savings outside the system. Mainly, however, the adequacy of the Superannuation Guarantee depends upon the standard of living that the system is seeking to provide in retirement, in combination with the age pension.

Existing caps on contributions to superannuation

Recognising that superannuation tax is concessional for most income earners, the system imposes annual limits on amounts that can be contributed to a fund. Individuals under age 49 may contribute $30,000 per year concessionally; those aged 49 and above may contribute $35,000.

All people aged up to 65 may contribute a further $180,000 each year, after tax. People aged under 65 have the ability to carry forward unused amounts of their annual $180,000 cap for up to three years ($180,000 x 3 = $540,000).

The current system also has a number of other concessions, including tax offsets for contributions made to the superannuation accounts of a low income spouse, and ‘transition to retirement’ (TRIS) pensions. TRISs allow older workers to access their superannuation funds while they are still in the workforce.

The 2016 superannuation reforms

The 2016 changes retain the existing TTE system of superannuation tax. The savings have been achieved by dialing down the level of permissible contributions, reducing the tax concessions for very high income earners. It is important to put in perspective, however, that the concessions are still very generous and still disproportionately benefit high income earners.

The headline changes in the final legislative package passed in 2016 are:

- Lower annual contributions caps and a lifetime limit of $1.6 million that can be contributed to superannuation;

- Higher contributions tax of 30 per cent applying to earnings of $250,000 and above;

- Abolition of the investment earnings tax exemption that supported TRIS pensions;

- Re-introduction of government support for low income earners; and

- Introduction of an objective for the superannuation system.

Changes to caps and increased tax for high income earners

The annual contribution caps have been reduced. All people – irrespective of age – may only make up to $25,000 each year in concessional contributions and up to $100,000 in non-concessional contributions. People aged under 65 can contribute up to $300,000 in one year under the carry-forward rule ($100,000 x 3 = $300,000). The annual $100,000 cap replaces the proposed cap of $500,000 in non-concessional contributions, which would have been backdated to 2007.

The 30 per cent rate of tax on contributions of high income earners will cut in at an income level of $250,000, rather than $300,000.

Lifetime limit on superannuation contributions

The new contributions caps are subject to a lifetime limit of $1.6 million which can be contributed to superannuation. In practice, those who hit this limit in mid-life will accumulate more than $1.6 million and the excess will be placed in an account paying 15 per cent earnings tax. Funds up to $1.6 million remain tax free in pension phase.

Abolition of investment earnings tax exemption for Transition to Retirement pensions

Transition to retirement (TRIS) pensions were introduced to assist workers to scale down to retirement. This was achieved through an exemption on earnings tax for older workers taking a (tax free) income stream from their superannuation, meaning that they could access a superannuation pension while they worked fewer hours. In effect, the scheme was used by many higher paid workers to lower their income tax. They achieved this through contributing to superannuation at a concessional rate, taking a tax-free pension, and lowering their income by the amount of the pension, thereby paying less income tax.

The 2016 reforms removed the earnings tax exemption supporting TRIS pensions. As TTPI has noted in its submission on the legislation, it is not clear to what extent this measure is going to address the issue of people being able to simultaneously contribute concessionally, while also not paying earnings tax in their pension account. TTPI has suggested applying an “on/off switch, whereby a fund is put in accumulating mode (taxable) if a person is contributing, and can only switch to pension mode (tax free) if contributions cease.

Low income earners

The Government has re-introduced support for low income earners, through the Low Income Superannuation Tax Offset (LISTO), replacing the Low Income Tax Offset. This means that people earning under $37,000 will not be subject to a tax penalty on their superannuation contributions, relative to the tax they would pay on their earnings.

The omission of gender measures

Just prior to the May Budget, a bipartisan Senate Committee released its report on the Economic Security of Women in Retirement, A Husband is not a Retirement Plan. The Committee made a series of recommendations, including distributing tax concessions more equitably; paying the superannuation guarantee on paid parental leave; and having an objective of superannuation that includes specific reference to women’s retirement incomes, to ensure gender equity is a continuing focus for policy makers.

In view of this, perhaps the most striking omission from the 2016 package is any substantive attempt to deal with the gender inequalities in superannuation. There is no mention of gender equity in the proposed objective of superannuation. Nor did the reforms address the penalty which women pay for taking time out of work to have children, or address the issue of superannuation contributions on paid parental leave.

Taken as a whole, the reforms leave women only marginally better off. This is because of the reintroduction of the Low Income Superannuation Tax Offset (LISTO) that will mainly benefit women as the majority of low income earners. The deferral of the spousal contributions concession until 1 July 2018 will disproportionately impact women as the primary beneficiaries of the lower threshold.

Workforce participation and interaction with the pension

In the context of an ageing population, measures to encourage older Australians to work are important. Older workers still face high effective marginal tax rates, with particular impacts on incentives to work and to save. To counter this, Ingles and Stewart (2015) have proposed a lower pension taper rate, for example 25 per cent, or shielding pensioners from tax until their income reaches the means test cut-out points.

As is so often the case in this area of policy, the superannuation changes have largely been assessed in isolation from the age pension. The changes to the pension means test which commence in January 2017 provide an incentive for middle income retirees to quickly run down their some of their superannuation savings, which goes against the purpose of superannuation even on the Government’s new legislation.

Further Changes to superannuation tax concessions? A conversation for another day

With the passage of the 2016 legislation, it is highly unlikely that we will see any further reforms to superannuation tax in the current term of parliament. The Opposition has proposed a series of further changes if it wins office at the next election that would result in an additional $1.4 billion in savings.

Both major parties have essentially committed to retaining the existing TTE system of superannuation taxation. What this means is that any future reforms are more likely to further tighten the existing concessions in the system, rather than institute a new tax structure. New tax structures have been canvassed by TTPI (Ingles and Stewart, 2015), Deloitte (2015) and in the Henry Review of Taxation (2009).

At least part of the reason why a systemic change to superannuation taxation has never really been on the table is because the cost of government expenditure on the tax concessions is contested. Treasury measures the revenue foregone on contributions and income on earnings tax, relative to the individual’s income tax rate. There are other ways of measuring the cost of the concessions.

Under one of these methods, superannuation contributions and earnings would be tax-exempt but benefits would be fully taxable when they are paid. As the Henry Review noted, the tax concessions under this benchmark are expected to be less because individuals will generally have a lower tax on their retirement income than while working. The Review also made the point that no matter which benchmark is used to measure expenditure, superannuation is taxed concessionally and the concessions are heavily weighted to individuals on higher personal tax rates.

Despite their complexity, the 2016 superannuation reforms are small target. As some commentators have noted, the biggest beneficiaries are likely to be financial advisers and accountants.

Recent Comments